Painting with Light - Stained Glass Decoration

How-to-Guide on stained glass windows - How little the art of stained glass has changed over the centuries.

In the 12th century, the monk Theophilus wrote a short how-to guide on stained glass windows. "If you want to assemble simple windows," he advised, "first mark out the dimensions of their length and breadth on a wooden board, then draw scrollwork or anything else that pleases you, and select colours that are to be put in. Cut the glass and fit the pieces together with the grozing iron. Enclose them with lead cames and solder on both sides. Surround it with a wooden frame strengthened with nails and set it up in the place where you wish."

History of Stained Glass

|

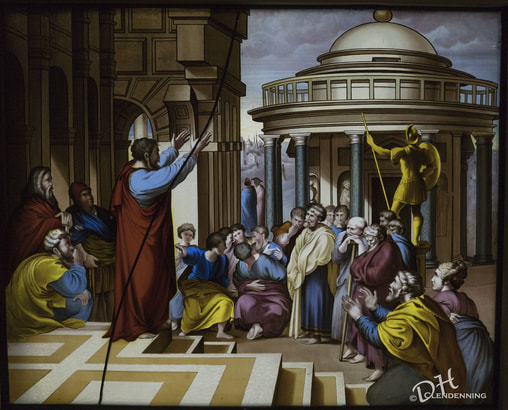

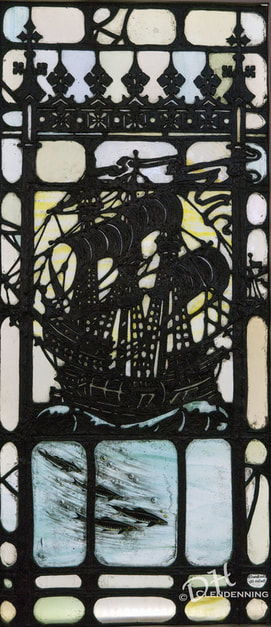

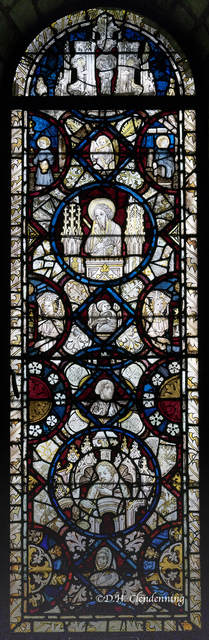

Roman Origins Although vessel glass was made in very early times, window glass seems to have been a Roman invention of the early Imperial period. The Romans used cast slabs of glass six inches square which were mounted in wooden frames. Slabs of this kind have been found at Pompeii, Herculaneum and Silchester (village in England). The Romans do not appear to have used translucent coloured glass for windows and this, as well as the invention of lead strips to hold the pieces of glass together, seem to have originated in the Byzantine world. We do not know when these two discoveries, crucial to the making of stained glass windows, took place, but the technique was certainly well established in Europe by 1110-30 when the monk Theophilus, who was probably from Germany wrote his famous Diversarium Artium Schedule. By the 12th century complex techniques of stained glass manufacture had evolved and the essential methods have remained more or less unaltered to the present day. The Middle Ages Stained glass is an art of colour, line and light. Stained glass windows are composed of two essential components - the glass itself, and the bonding, traditionally in the form of strips of lead, and the bonding, traditionally in the form of strips of lead, which hold the glass together. The glass, usually coloured, may be augmented by overprinting in enamels to add tone, texture, and detail. Historically, the combination of pieces of coloured glass came about as a response to a technical limitation. Duringt the Middle Ages in Europe, glass making techniques could not produce pieces of sufficient size to to span the height and width of window opening in churches which grew larger as the art of architecture progressed, climaxing in the the enormous window opening of the great Gothic cathedrals and churches of the High Middle Ages. To overcome this liability, deigns used strips of lead to enable them to assemble many small pieces of glass into a matrix large enough to fill the dimensions of a window opening. The genius of stained glass design lay in part in incorporating the headlines as a technical necessity into the aesthetics of the overall design, outlining and accenting compositions in a matter making to the outlines of modern colouring books. Revival During the Nineteenth Century While the art of stained glass was in decline from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, it underwent a spectacular revival during the 1800s. The revival of stained glass art took place in the dual context of growing interest in the art and architecture of the Middle Ages, and the effects in glass making brought about by advances in chemistry and technology associated with the Industrial Revolution. Two essential types of glass emerged in stained glass design in the 1800s. So-called "antique" glass was not old glass, but hand blown glass. In contrast, "cathedral" glass, was machine made, with hot glass passed through metal rollers. As the result of studies by antiquarians and scientists alike, glassmakers of the 1800s re-invented what came to be called the "true mosaic process", using contoured headlines to outline and augment compositions of multiple pieces of coloured glass. Enamel Paining Enamel painting derived from traditions dating back as far as the 1400s and much used by many stained glass artists of the 1800s and even early 1900s. In Canada, enamel painting was used on plain or white glass when coloured glass was either unavailable or prohibitive in cost. The glass obtained by stained glass studios in Canada was always imported, often from Great Britain, but also from France, Germany and the United States. |

Remove Not The Ancient Landmark, Which Thy Fathers Have Set. |

Stained Glass as Monument Art - To understand history architecture, light and space

The ethereal beauty of medieval stained glass windows

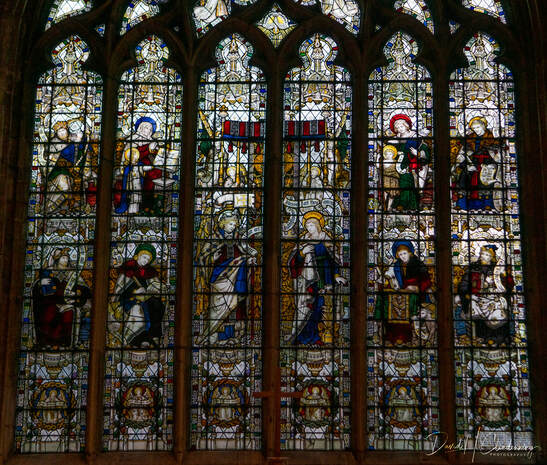

Stained glass windows are never static. In the course of the day they are animated by changing light, their patterns wandering across the floor, inviting your thoughts to wander with them. They were essential to the fabric of ancient churches, illuminating the building and the people within, both literally and spiritually. Images and scenes leaded together into windows shed light on the centre drama of Christain salvation. They allowed the light of God into the church.

The ethereal beauty of medieval stained glass windows

Stained glass windows are never static. In the course of the day they are animated by changing light, their patterns wandering across the floor, inviting your thoughts to wander with them. They were essential to the fabric of ancient churches, illuminating the building and the people within, both literally and spiritually. Images and scenes leaded together into windows shed light on the centre drama of Christain salvation. They allowed the light of God into the church.

Life, like a dome of many coloured glass, stains the white radiance of eternity - Percy Bysshe Shelley

Title: Exterior View of King's College Chapel, c.1446, Cambridge.

Reference No.: A1-6352.

Title: Exterior View of King's College Chapel, c.1446, Cambridge.

Reference No.: A1-6352.

No amount of photographic skill can replace the pleasure of seeing stained glass windows brought to life by the magic of light in the buildings for which they were specially designed and made.

Emmanuel College, Cambridge (c. 1584) - Connection to Harvard University, Boston

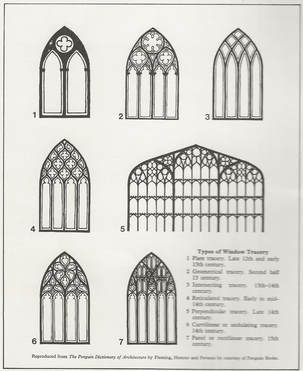

Stained Glass Window Tracery

Types of Window Tracery

Types of Window Tracery

Types of Window Tracery

1. Plate tracery. Late 12th and early 13th century.

2. Geometrical tracery. Second half 13 century.

3. Interesting tracery. 13th-14th century.

4. Reticulated tracery. Early to mid-14th century.

5. Perpendicular tracery. Late 14th century.

6 Curvilinear or undulating tracery. 14th century.

7. Panel or rectilinear tracery. 15th century.

Reproduced from The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture, Penguin Books

1. Plate tracery. Late 12th and early 13th century.

2. Geometrical tracery. Second half 13 century.

3. Interesting tracery. 13th-14th century.

4. Reticulated tracery. Early to mid-14th century.

5. Perpendicular tracery. Late 14th century.

6 Curvilinear or undulating tracery. 14th century.

7. Panel or rectilinear tracery. 15th century.

Reproduced from The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture, Penguin Books

Oxford and University Colleges

Merton College

Balliol College

Exeter College

St. Mary the Virgin Church, Oxford

Oxford University Library

Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

Click on image to enlarge.

Painting with Light

Buckinghamshire

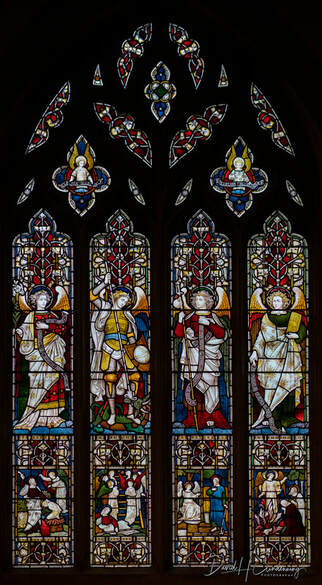

St Michael and All Angels' Church is a Grade: II listed Anglican church in the Hughenden Valley, Buckinghamshire, England, near to High Wycombe. It is closely associated with the nearby Hughenden Manor and the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Benjamin Disraeli who is buried in the churchyard (see UK Architecture).

Lincolnshire

Lincoln Cathedral

St. Wulfram's Church, Grantham, Lincolnshire

Glass Heritage in the United Kingdom

For at least thirteen hundred years the art of making stained glass windows has been practised in England. The earliest known work was in 675 when imported workmen from France glazed the windows of the monastery of St. Peter, Monkwearmounth, Northumberland. But the use of window glass goes back much further in history to Roman times.

Glass in Monasteries, Castles, Parish Churches, Cathedrals, Colleges, Houses and Guild Houses

Images for educational purposes only

A significant contribution to the art of Gothic Europe as a whole was the splendid fifteenth-century output in England of painted glass.

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

Cornwall

Flemish (Imported to England)

Medieval England

|

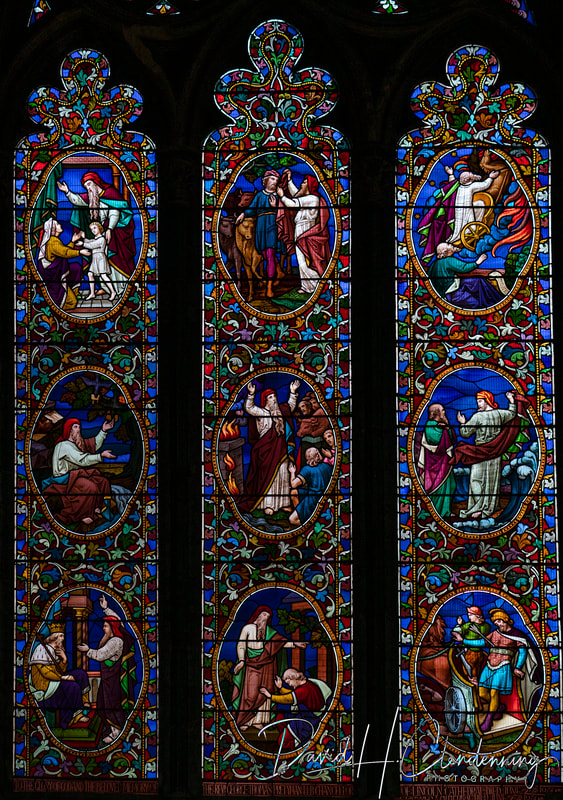

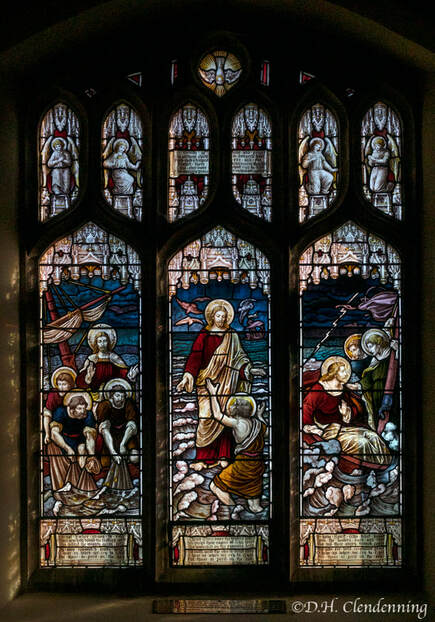

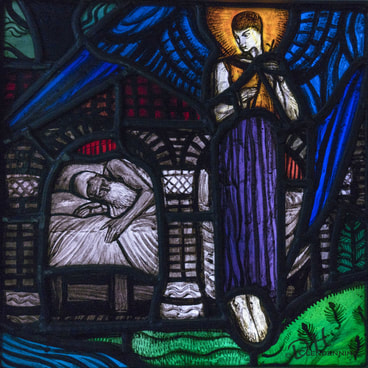

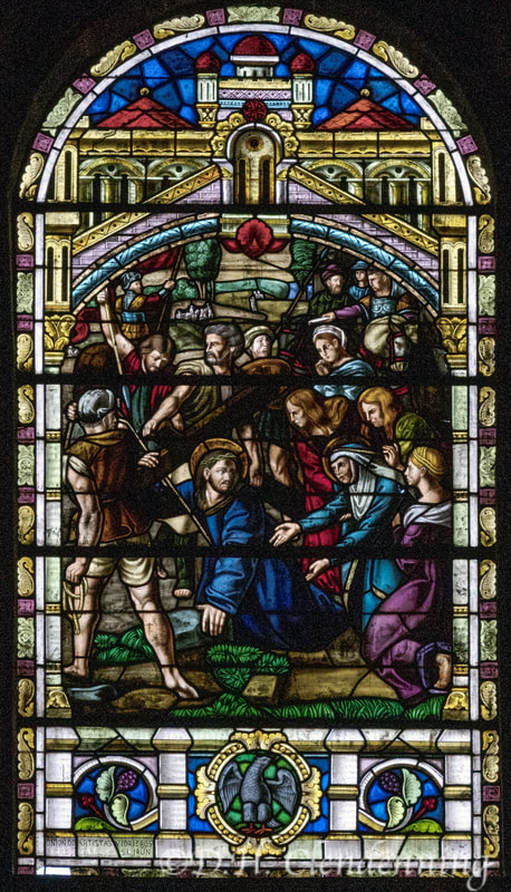

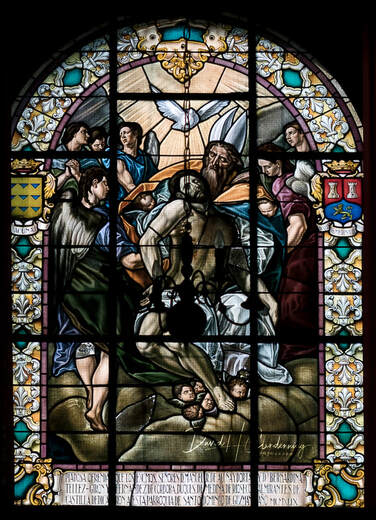

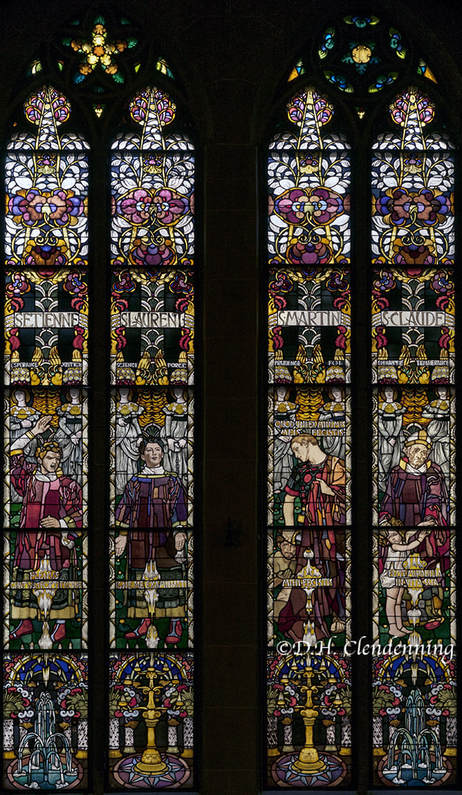

Subjects for the glass derive from Scripture, from standard themes in Christian theology, and also relate to the cycle of the Christain year and even to the functions of part of the building. For example, glass many contain Eucharistic reference to bread and wine. The subject of Christ blessing children was frequently chosen for memorials in stained glass, part of its topicality dating back to 1800 when infant morality was much higher than in subsequent decades. The Good Shepard shows another subject suitable as a memorial for a child dying in infancy. Another subject would be the depiction of Christ healing a sick woman. The most elaborate stained glass windows often included architectural details stimulating the carved canopies over statuary.

|

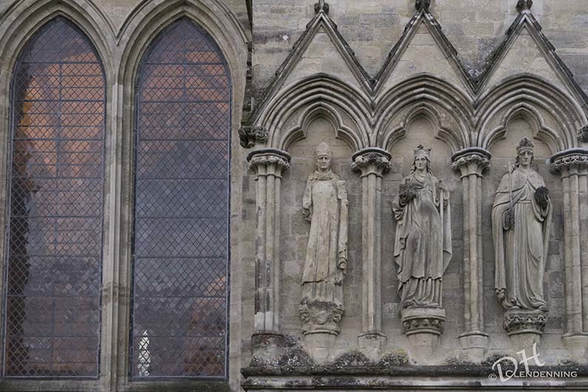

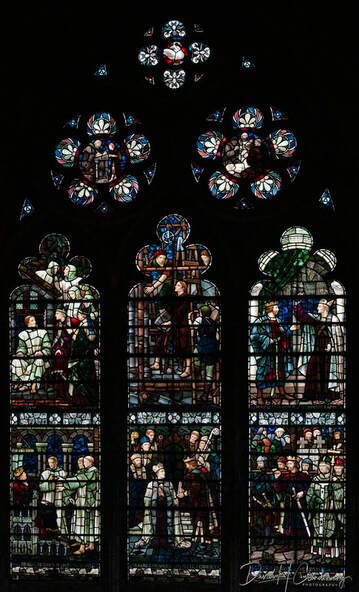

In Medieval times, architects of the great Gothic cathedrals made use of sculptural decoration and stained glass in order to both beautify the sacred space, and instruct the illiterate masses in the most fundamental Bible stories and tenants of the faith.

Norfolk

St Mary Magdalene Parish Church, Sandringham, Norfolk

The parish church of St Mary Magdalene, Sandringham, is a country church of exceptional historic interest, with memorials to many members and relations of the Royal Family from Queen Victoria onwards. It is used regularly as a place of worship by the Royal Family and Estate staff.

Sandringham Church is considered to be one of the finest carrstone buildings in existence, and dates back in its present form to the 16th century.

Sandringham Church is considered to be one of the finest carrstone buildings in existence, and dates back in its present form to the 16th century.

Yorkshire

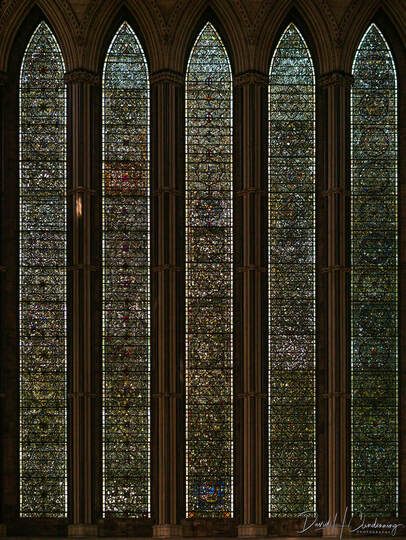

York Cathedral

These five 13th century lancet (called the Five Sisters by Charles Dickens) windows date from around 1260, contemporary with the building of the north transept at the Minster. The grisaille glass contains about 100,000 individual pieces. It was re-leaded in 1923-5 using 13th century lead from Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire.

The 13th century window is filled with grisaille glass (from the French for greyness) – finely painted clear glass set into geometric designs with jewel-like points of coloured glass making the pattern.

The 13th century window is filled with grisaille glass (from the French for greyness) – finely painted clear glass set into geometric designs with jewel-like points of coloured glass making the pattern.

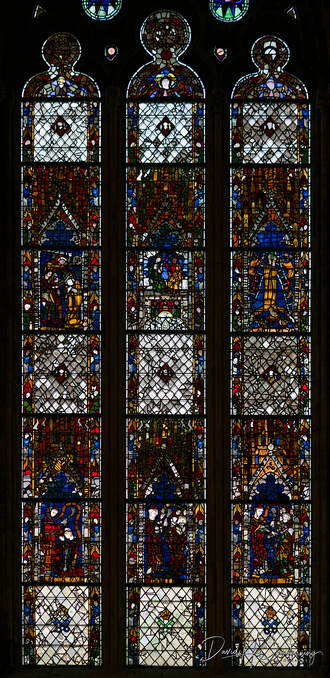

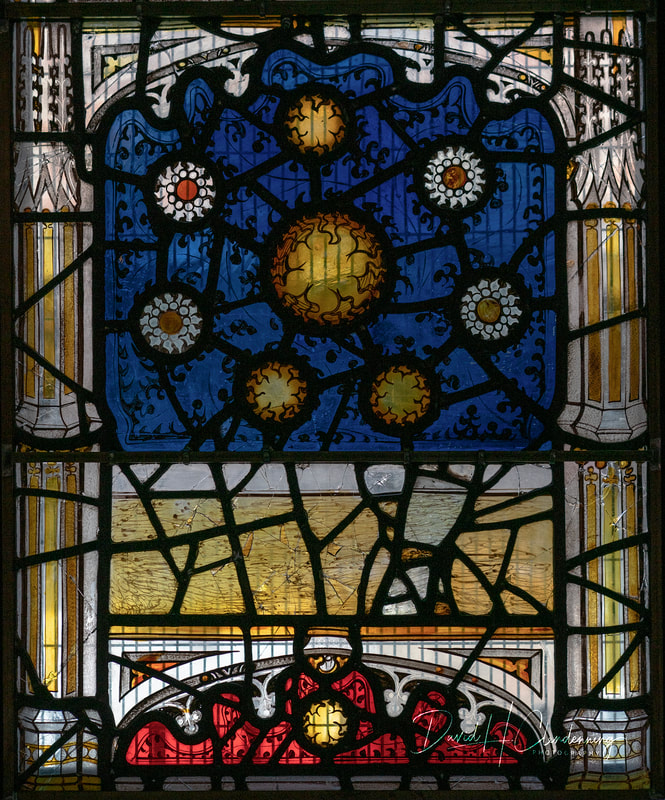

Chapter House, c. 1290 - c.1350

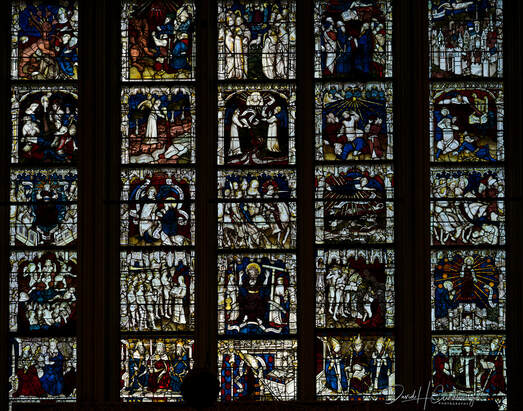

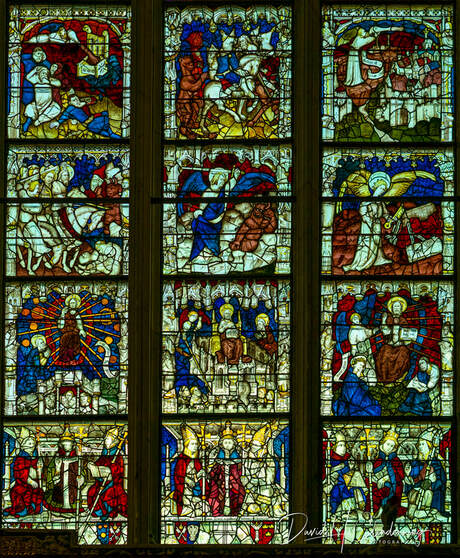

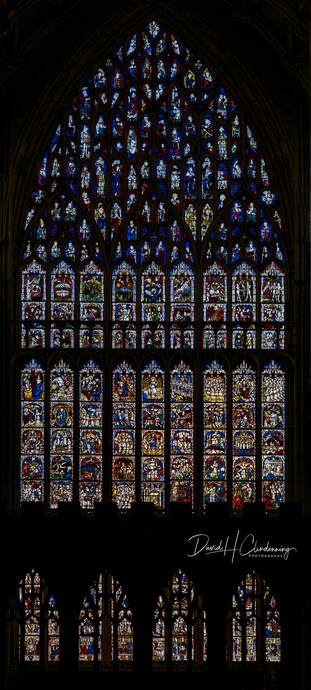

Great East End Window, York Cathedral created between 1405-8 by master glazer John Thornton. This is the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in England. It tells the story of the world from beginning to end, as described in the Books of Genesis and Revelation.

The stonework and glass of this beautiful has only been revealed in all its glory since 2018, following one of Europe's largest conservation and restoration projects.

The stonework and glass of this beautiful has only been revealed in all its glory since 2018, following one of Europe's largest conservation and restoration projects.

The Great East Window is one the great artistic achievements of the Middle Ages, a stunning expanse of stained glass of unparalleled size and beauty in Britain.

Half of the window depicts the creation of the world from the Book of Genesis. The other half tells the story of the Book of Revelations and the events that presage the return of Christ and the end of the world.

Half of the window depicts the creation of the world from the Book of Genesis. The other half tells the story of the Book of Revelations and the events that presage the return of Christ and the end of the world.

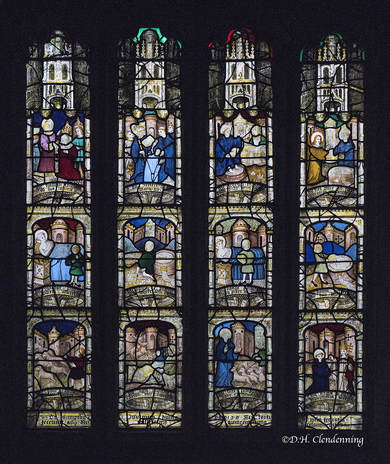

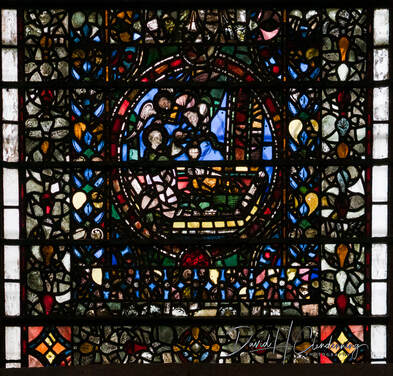

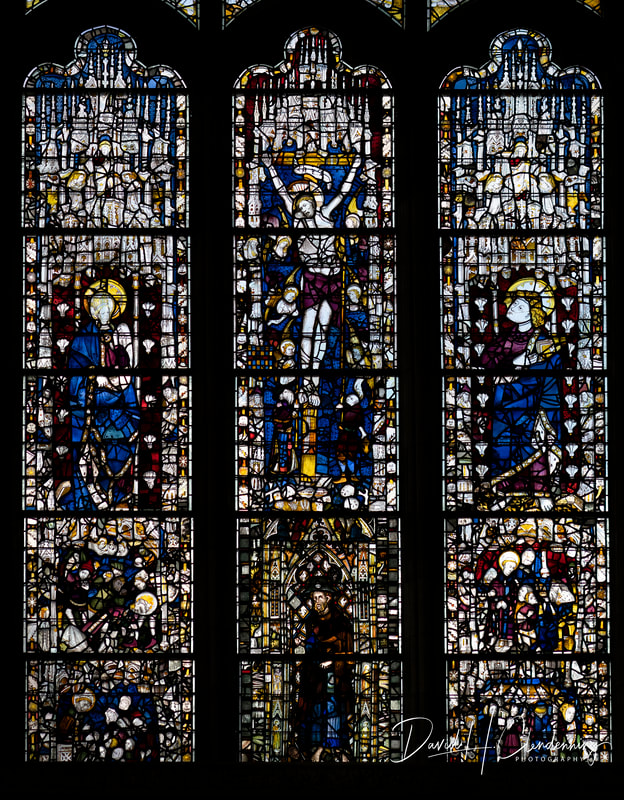

The Medieval Stained-Glass Windows of All Saints Church, North Street, York

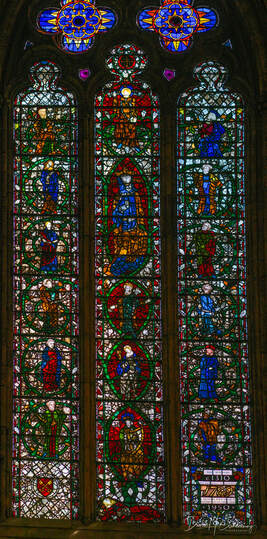

The ten windows of All Saints North Street in York form one of the great set pieces of English medieval art.

The Lady Chapel east window (c.1330)

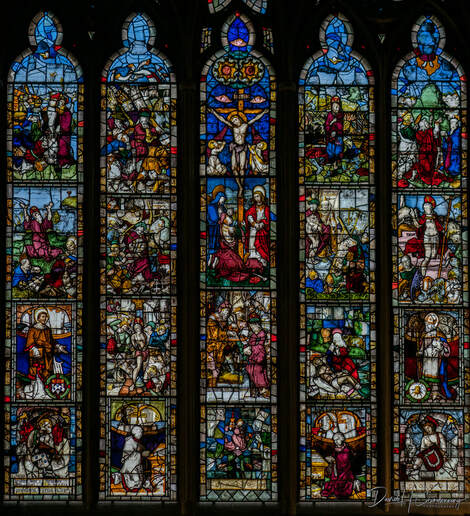

From the main window the various panes are described:

1. Left Light, Lower: The annunciation (the angel) Gabriel tells Our Lady she is to be the mother of God's Son. The angel holds a scroll with the words 'Ave Maria gratis Elena', 'Hail Mary full of grace' (Luke 1.28; the Latin words are abbreviated).

2. Centre Light, Lower: The Nativity (the birth of Jesus). Our Lady holds the infant Jesus, S. Joseph is beside her, and above them are heads of an ox and an ass.

3. Left Light, Upper: The Adoration of the Maja (the three kings offer gifts to the infant Christ).

4. Centre Light, Upper: The Crucifixation. With the crucified Jesus is the customary pairing of ur Lady (left) and S. John.

5. Right Light, Lower: The resurrection of Jesus. He is shown rising from the tomb. At one side is an angel in white, and below are three soldiers, the centre one frightened and awake, the outer ones asleep.

6. Right Light, Upper: The Coronation of Our Lady as Queen of heaven - in medieval thought the sign that the redemption of humanity by God in Christ is completed.

1. Left Light, Lower: The annunciation (the angel) Gabriel tells Our Lady she is to be the mother of God's Son. The angel holds a scroll with the words 'Ave Maria gratis Elena', 'Hail Mary full of grace' (Luke 1.28; the Latin words are abbreviated).

2. Centre Light, Lower: The Nativity (the birth of Jesus). Our Lady holds the infant Jesus, S. Joseph is beside her, and above them are heads of an ox and an ass.

3. Left Light, Upper: The Adoration of the Maja (the three kings offer gifts to the infant Christ).

4. Centre Light, Upper: The Crucifixation. With the crucified Jesus is the customary pairing of ur Lady (left) and S. John.

5. Right Light, Lower: The resurrection of Jesus. He is shown rising from the tomb. At one side is an angel in white, and below are three soldiers, the centre one frightened and awake, the outer ones asleep.

6. Right Light, Upper: The Coronation of Our Lady as Queen of heaven - in medieval thought the sign that the redemption of humanity by God in Christ is completed.

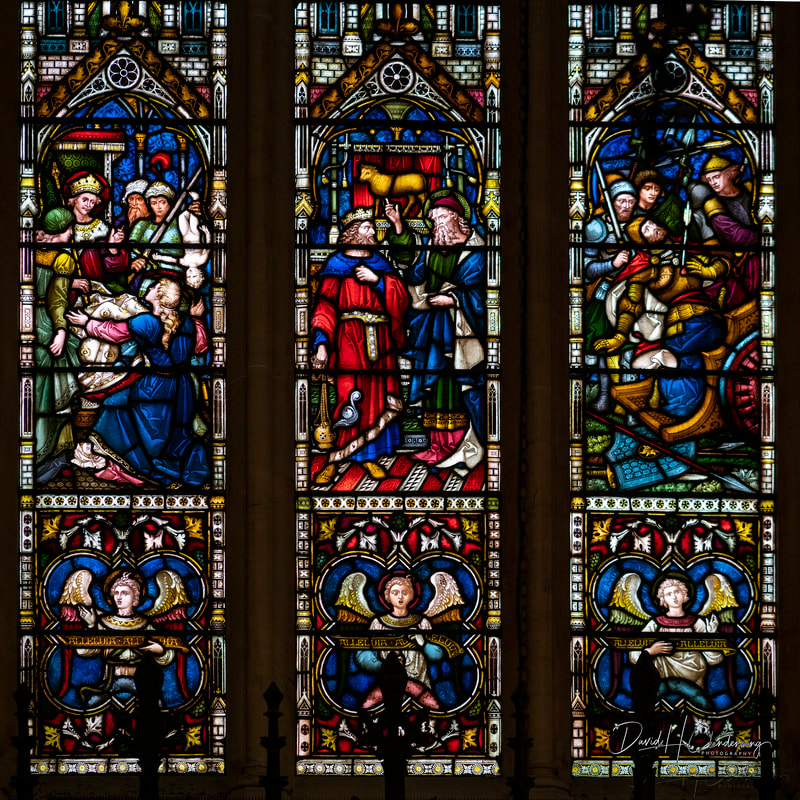

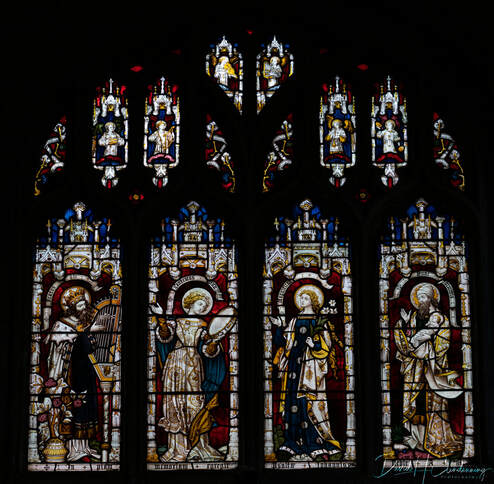

The S. James window:

Left Light: S. James the apostle, dressed as a pilgrim on this way to the Santiago shrine at Compostela. ('lago' is the Spanish form of 'Iacobus', James.)

Centre Light: Our Lady, crowned, holding her Child.

Right Light: A kneeling archbishop. His mitre is behind him, and he is wearing the pallium around his neck, the symbol of archiepiscopal authority bestowed by the pope. This is saying Mass and is kneeling at the elevation of the Host. Above him Christ appears, accompanied by four angels.

Left Light: S. James the apostle, dressed as a pilgrim on this way to the Santiago shrine at Compostela. ('lago' is the Spanish form of 'Iacobus', James.)

Centre Light: Our Lady, crowned, holding her Child.

Right Light: A kneeling archbishop. His mitre is behind him, and he is wearing the pallium around his neck, the symbol of archiepiscopal authority bestowed by the pope. This is saying Mass and is kneeling at the elevation of the Host. Above him Christ appears, accompanied by four angels.

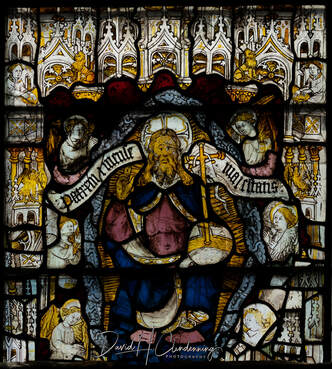

Shown in the left of the window, is St. Thomas the Apostle, known as 'Doubting Thomas' because according to S. John's Gospel he refused to believe in the resurrection of Christ until he saw and touched him. The scroll behind his head reads 'Dominus mess et Deus meus', My Lord and my God', Thomas's confession of faith when the risen Christ showed himself.

In the Centre Light is the Risen Christ, who shows to S. Thomas the visible wounds to has hands, feet and side.

In the right Light, is a different S. Thomas, S. Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury murdered in his cathedral in 1170.

In the Centre Light is the Risen Christ, who shows to S. Thomas the visible wounds to has hands, feet and side.

In the right Light, is a different S. Thomas, S. Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury murdered in his cathedral in 1170.

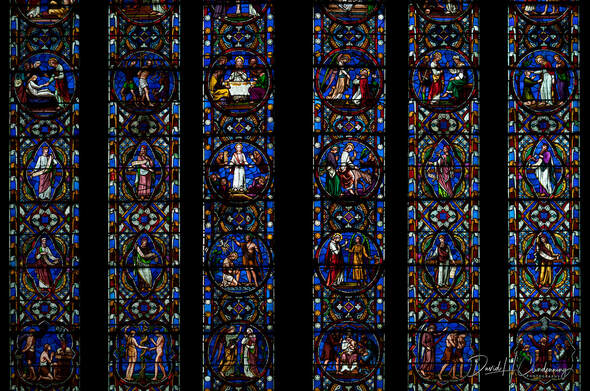

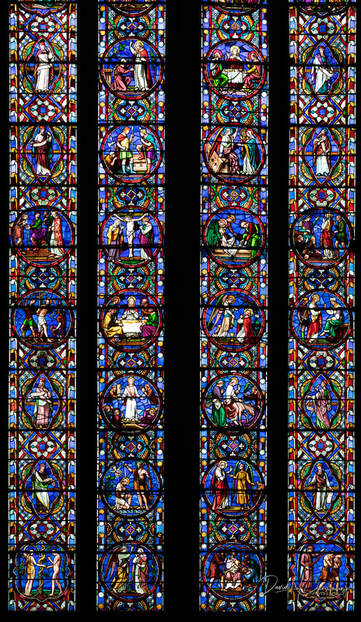

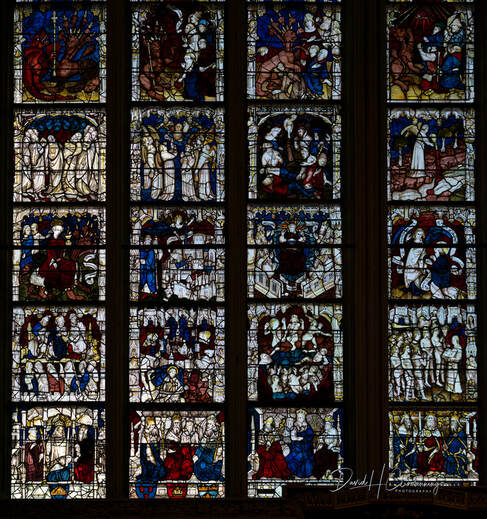

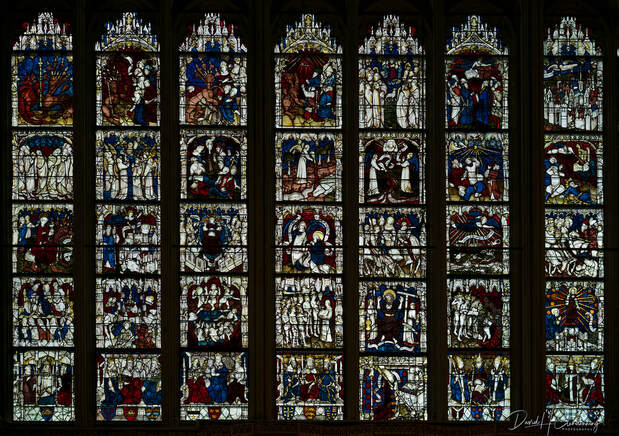

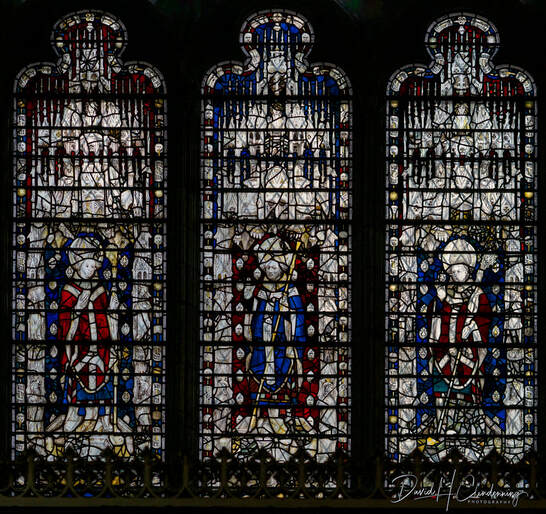

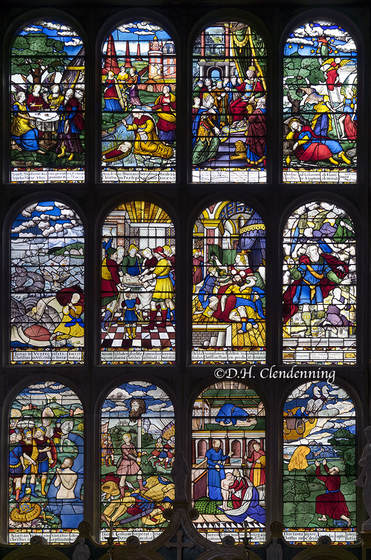

Prickle of Conscience window (1410)

This unique window (1410) and the finest in the church, illustrates part of a widely popular devotional poem of c. 1340, 'The Price of Conscience'. The anonymous poem is written in the Northumbrian dialect of Middle English. The part illustrated concerns the End of the World, depicted in fifteen signs or 'days' - the last fifteen days of the world. It is Europe's one known medieval window to incorporate the text of a poem it illustrates below each scene.

It is thought likely on stylistic grounds that the glass painter was John Thornton of Coventry, who made the huge was window of York Minister in 1405-8, the world's largest expanse of medieval glass.

The photo of the window above was taken in three sections to ensure a clear capture of the images and its clarity. Note the repeat of the top line in the middle and bottom images.

The fifteen 'days' are (left to right):

Line one:

1. The stars fall from heaven.

2. All living people die.

3. The whole cosmos goes up in flames.

Line two:

4. Only the featureless earth and red sky remain.

5. People come out of caves praying. (One man is still hiding!)

6. The graves are opened

Line three:

7. Earthquakes destroy buildings.

8. Rocks and stones are consumed by fire.

9. People take refuge in caves.

Line four:

10. Fish leap out of the sea 'roaring'.

11. The sea catches fire.

12. Fruit drops off the trees.

Line Five:

13. The sea floods.

14. The sea recedes, exposing the sea-bed.

15. The sea returns to its normal level.

Live Six:

kneeling donors.

It is thought likely on stylistic grounds that the glass painter was John Thornton of Coventry, who made the huge was window of York Minister in 1405-8, the world's largest expanse of medieval glass.

The photo of the window above was taken in three sections to ensure a clear capture of the images and its clarity. Note the repeat of the top line in the middle and bottom images.

The fifteen 'days' are (left to right):

Line one:

1. The stars fall from heaven.

2. All living people die.

3. The whole cosmos goes up in flames.

Line two:

4. Only the featureless earth and red sky remain.

5. People come out of caves praying. (One man is still hiding!)

6. The graves are opened

Line three:

7. Earthquakes destroy buildings.

8. Rocks and stones are consumed by fire.

9. People take refuge in caves.

Line four:

10. Fish leap out of the sea 'roaring'.

11. The sea catches fire.

12. Fruit drops off the trees.

Line Five:

13. The sea floods.

14. The sea recedes, exposing the sea-bed.

15. The sea returns to its normal level.

Live Six:

kneeling donors.

North Yorkshire

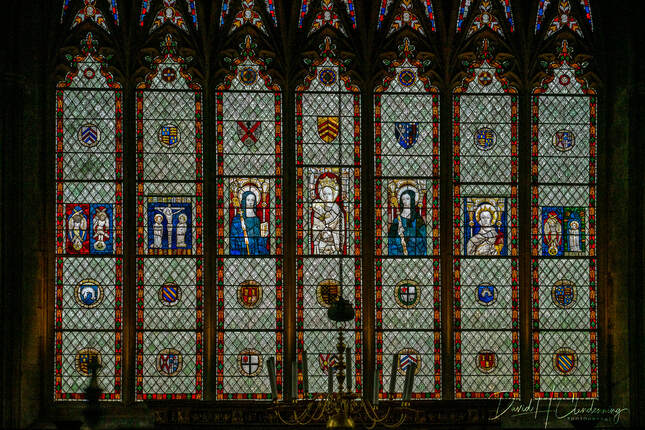

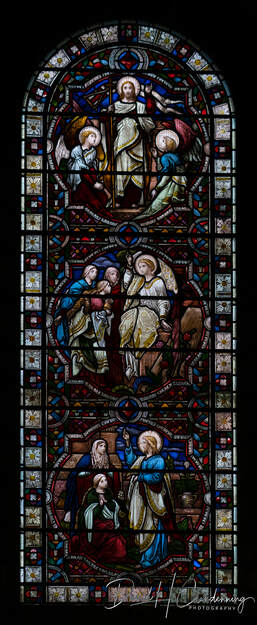

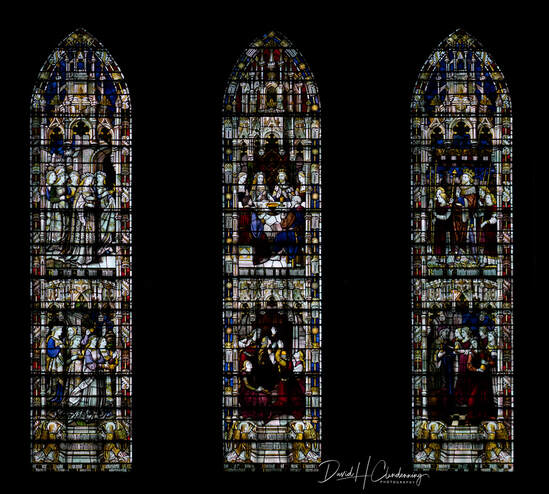

Ripon Cathedral, Yorkshire - Victorian Stained Glass Windows

Wise Memorial: Ascension:

The risen Jesus is shown ascending into heaven, while his disciples look up in awe. This is a particularly dramatic interpretation of the Ascension, with the light of heaven radiating around the figure of Jesus.

The risen Jesus is shown ascending into heaven, while his disciples look up in awe. This is a particularly dramatic interpretation of the Ascension, with the light of heaven radiating around the figure of Jesus.

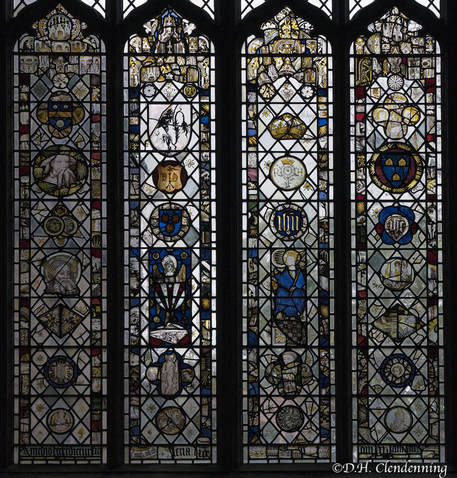

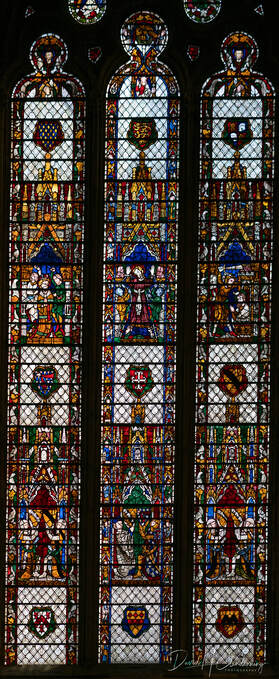

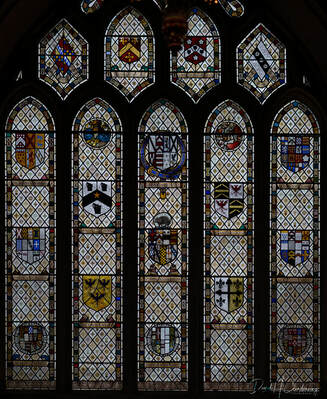

Lord Grantley Window: Among the coats of arms are those of Edward 111 (left light top) and John of Gaunt (right light middle). In the second row of the central shield, the second 'quarter' from the left, is for Sir William de Washington, who bore the same shield as George Washington, 1st President of the USA. His shield has the origin of the Stars and Strips flag design. But these are not stars! They are pierced in the centre and are, in fact, spur rowels (the revolving part of a spur). Perhaps the American flag should be called the Spurs and Stripes!

Above the central shield is a crest with a Moor's head. One tradition says that a black servant rescued one of the family from drowning.

Above the central shield is a crest with a Moor's head. One tradition says that a black servant rescued one of the family from drowning.

Bath Abbey, Bath, England

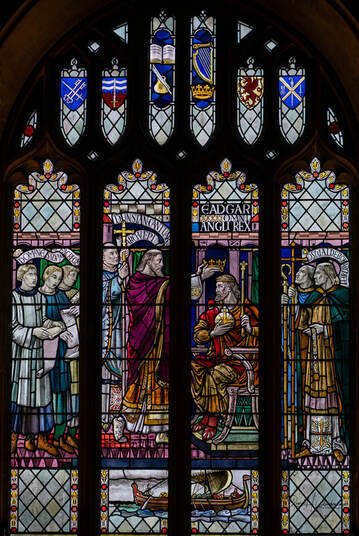

A church fit for a king

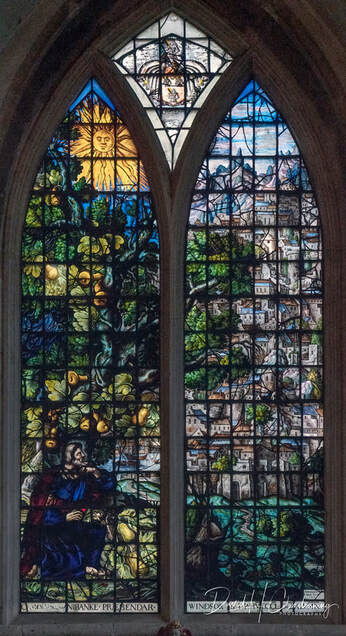

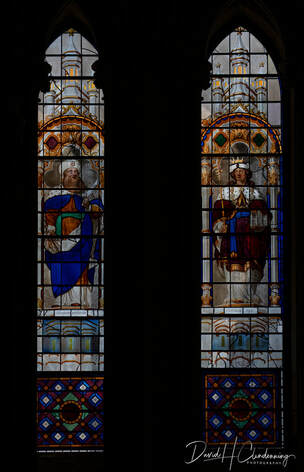

Edgar was the first king to be crowned "King of All England" in the year 973. His coronation service shown in this window, took place at the Anglo-Saxon monastery in Bath.

During the service, Edgar promised a rule of peace, to stop people doing wrong, and to be fair ad merciful in his judgements. The main parts of the service - written by Dunstan (the Archbishop of Canterbury, dressed in purple on the left of the window) - are still used to crown British kings and queens today.

The Anglo-Saxon monastery was know to be a "remarkable " building. In it, monks made the worship of God and the care of others the purpose of their lives. Christians across the world continue to do the same thing today.

Edgar was the first king to be crowned "King of All England" in the year 973. His coronation service shown in this window, took place at the Anglo-Saxon monastery in Bath.

During the service, Edgar promised a rule of peace, to stop people doing wrong, and to be fair ad merciful in his judgements. The main parts of the service - written by Dunstan (the Archbishop of Canterbury, dressed in purple on the left of the window) - are still used to crown British kings and queens today.

The Anglo-Saxon monastery was know to be a "remarkable " building. In it, monks made the worship of God and the care of others the purpose of their lives. Christians across the world continue to do the same thing today.

The Great East Window of Bath Abbey

Hereford Palace at the time of Elizabeth 1.

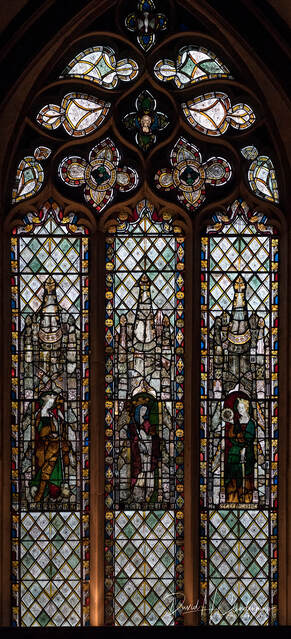

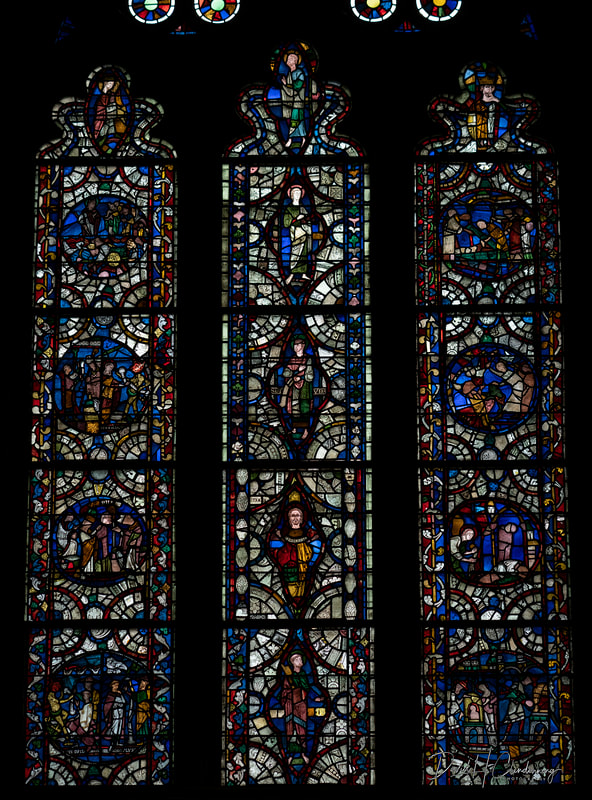

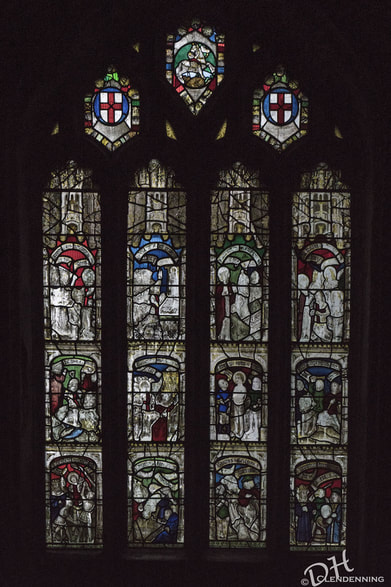

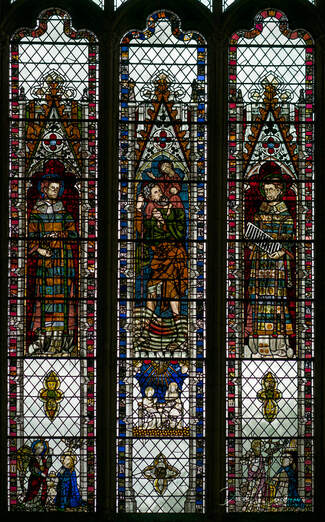

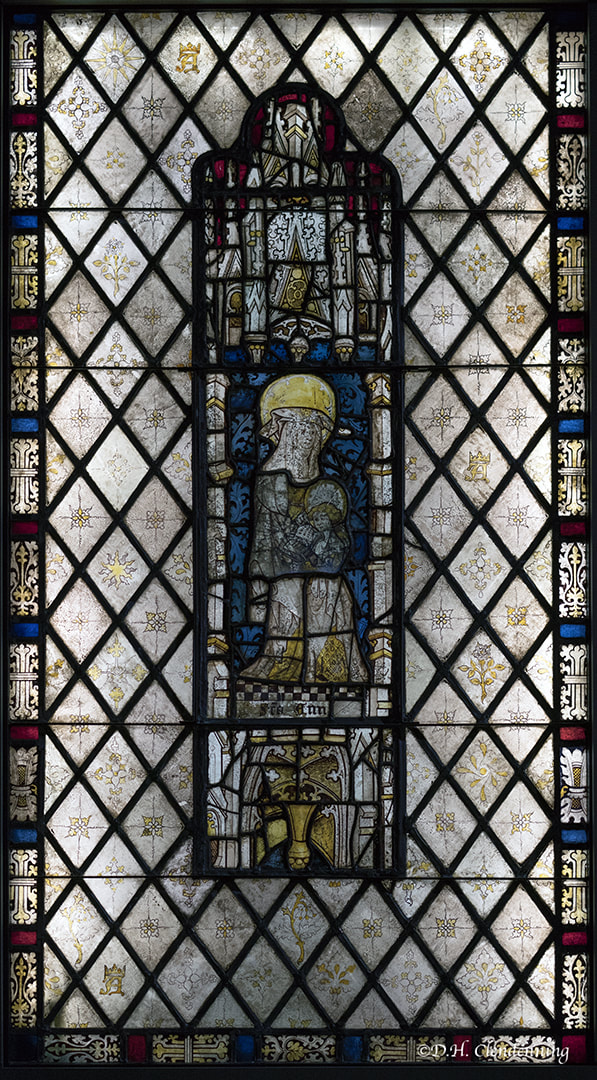

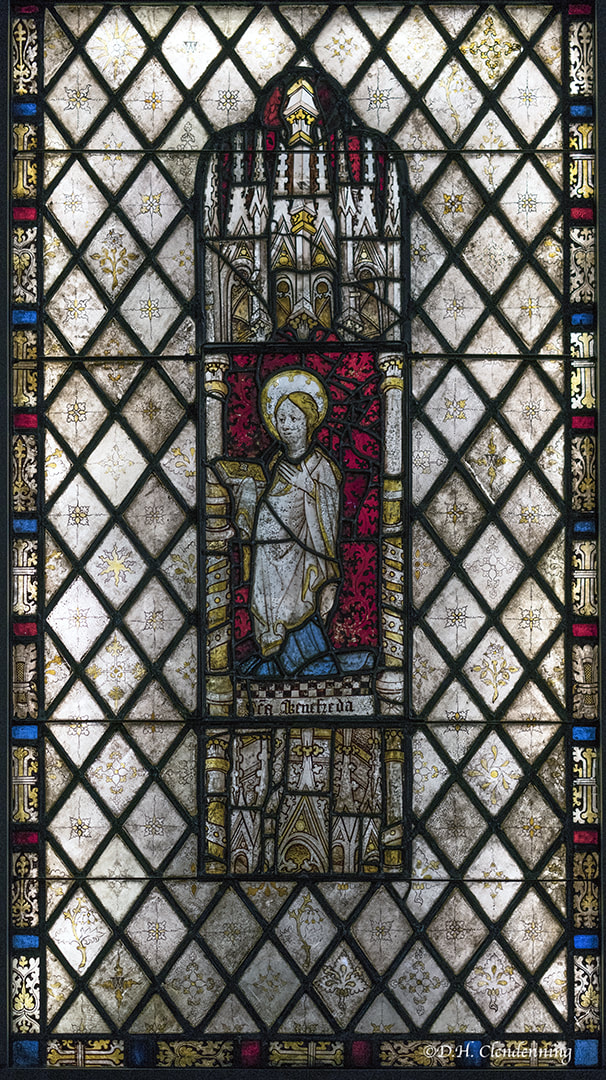

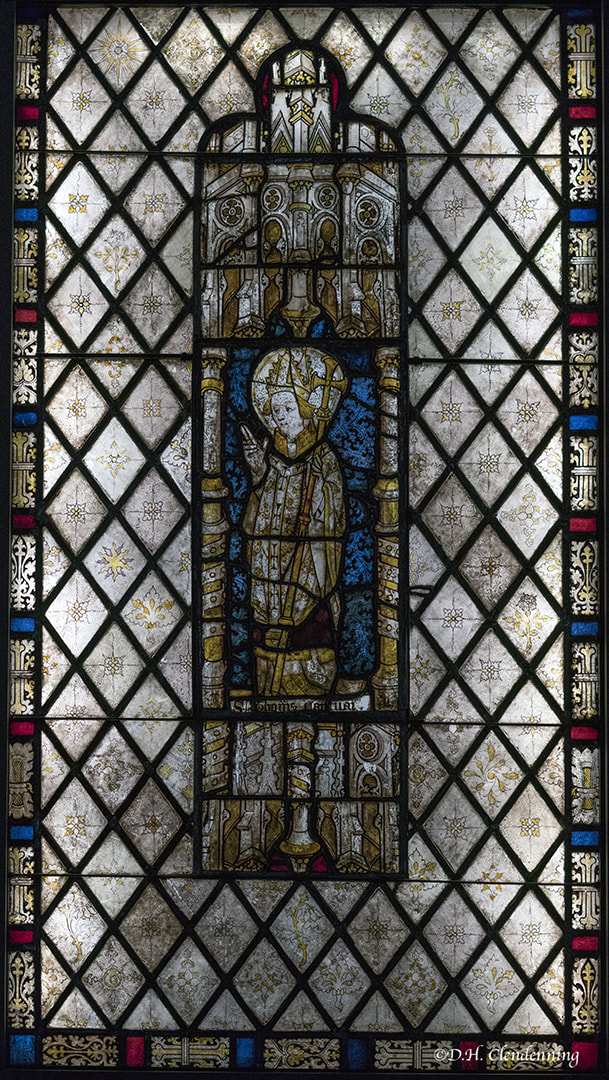

Three Lancet Medieval Windows, York School, Hereford, About 1435 - Pot-metal glass, clear glass with silver stain, leading.

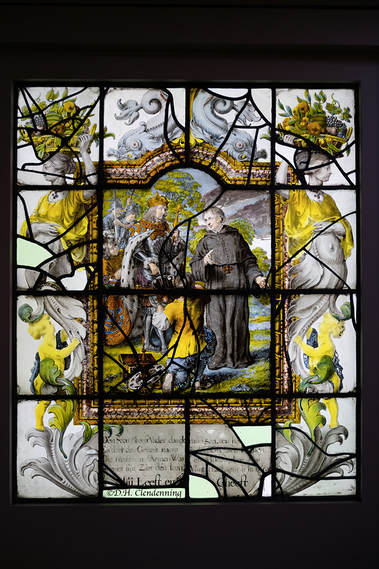

These three lancet windows, exceptional examples of fifteenth-century painted stained glass, are attributed to an artist from the region of Hereford. They have been traced to the domestic chapel of Hampton Court, near Leominster, Herefordshire. All three depict saints; Saint Anne teaching her daughter, the Virgin Mary to read; Saint Winifred, a Welsh saint who was admired in medieval Britain; and Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was murdered by Henry 11 in 1170.

The colours of the glass are restricted to red and blue, with yellow highlights that resulted from the application of a fiver stain to the white glass. The emphasis in on painted line rather than pure colour, and the draftsmanship, modelling of the figures and fluid lines of the drapery are extremely skillful. The placement of the figures under an architectural canopy against a ground of vegetal motifs or textile patterns was a common feature of fifteenth-century English stained glass.

- Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

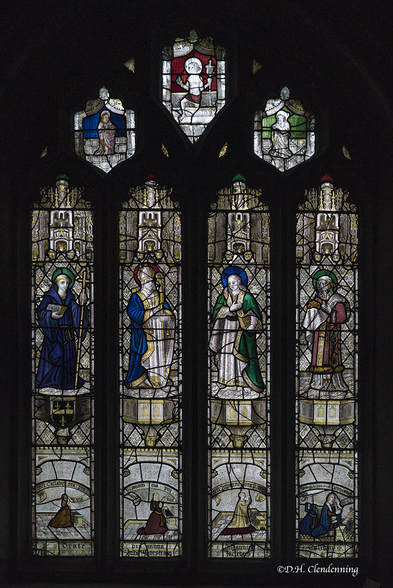

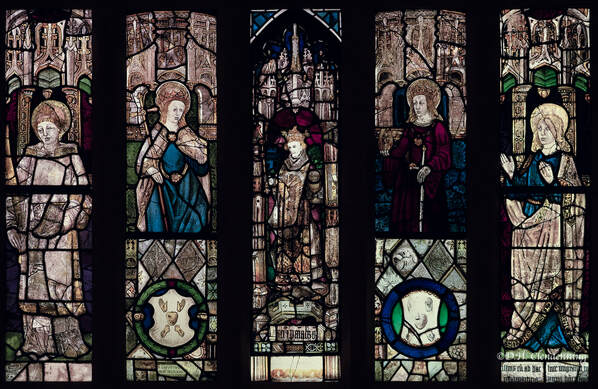

Composite Window of English Stained Glass

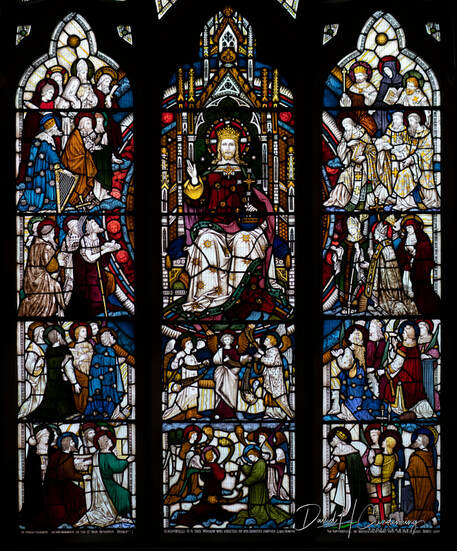

c. 1450-60, Pot-metal glass, colourless glass, vitreous paint, and silver stain. King Edward the Confessor (above centre)

c. 1450-60, Pot-metal glass, colourless glass, vitreous paint, and silver stain. King Edward the Confessor (above centre)

The Stained Glass Museum, Ely Cathedral, England - Display Notations

See notes below on Ely Stained Glass Musuem, England.

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

SGM contains a major collection of stained-glass panels from ancient to modern times, plus glassmaking tools & Materials

Comments are based on individual research for educational purposes only. From display materials at the Stained Glass Museum (SGM), one gains an unique insight into the fascinating history of stained glass, an art-form that has been practised in Britain for at least thirteen hundred years. Photographs are not for sale.

Click to enlarge and read

Changing Styles

The style of stained glass, known as Gothic, developed during the Medieval period, reflecting the elegant soaring architecture of the same name used in churches and cathedrals.

During 1600-1800, the Gothic style of stained glass declined in popularity. Circumstances in the early 1800s favoured a revival.

The Industrial Revolution resulted in the rapid expansion of towns and cities, which required new churches for their growing populations. From 1829 Roman Catholics could worship freely, further boasting demand for new churches.

Initially, a variety of different architectural styles competed for popularity aiming to reflect the country's growing self-confidence. When a medieval design was chosen for the new Houses of Parliament in 1835, the balance tipped in favour of the Gothic style.

New building required new furnishing to match. The brilliant pioneering architect and designer, N. W. N. Pugin who worked with Charles Barrie on the design for the new Houses of Parliament, led the revival in stained glass. His designs recaptured the style of medieval work, while artist-craftsmen like Thomas Willement, William Wailes, William Warrington and John Hardman revived the 'mosaic' craft techniques of the Middle Ages.

The style of stained glass, known as Gothic, developed during the Medieval period, reflecting the elegant soaring architecture of the same name used in churches and cathedrals.

During 1600-1800, the Gothic style of stained glass declined in popularity. Circumstances in the early 1800s favoured a revival.

The Industrial Revolution resulted in the rapid expansion of towns and cities, which required new churches for their growing populations. From 1829 Roman Catholics could worship freely, further boasting demand for new churches.

Initially, a variety of different architectural styles competed for popularity aiming to reflect the country's growing self-confidence. When a medieval design was chosen for the new Houses of Parliament in 1835, the balance tipped in favour of the Gothic style.

New building required new furnishing to match. The brilliant pioneering architect and designer, N. W. N. Pugin who worked with Charles Barrie on the design for the new Houses of Parliament, led the revival in stained glass. His designs recaptured the style of medieval work, while artist-craftsmen like Thomas Willement, William Wailes, William Warrington and John Hardman revived the 'mosaic' craft techniques of the Middle Ages.

Looking Back

A number of influential historical studies in 1840-50 gave craftsmen and designers invaluable information about the Middle Ages. The most important were by Charles Winston, a patent lawyer and amateur historian. His studies made him aware of the short-comings of the glass available to artist of his own day, which was often thin and garish in colour.

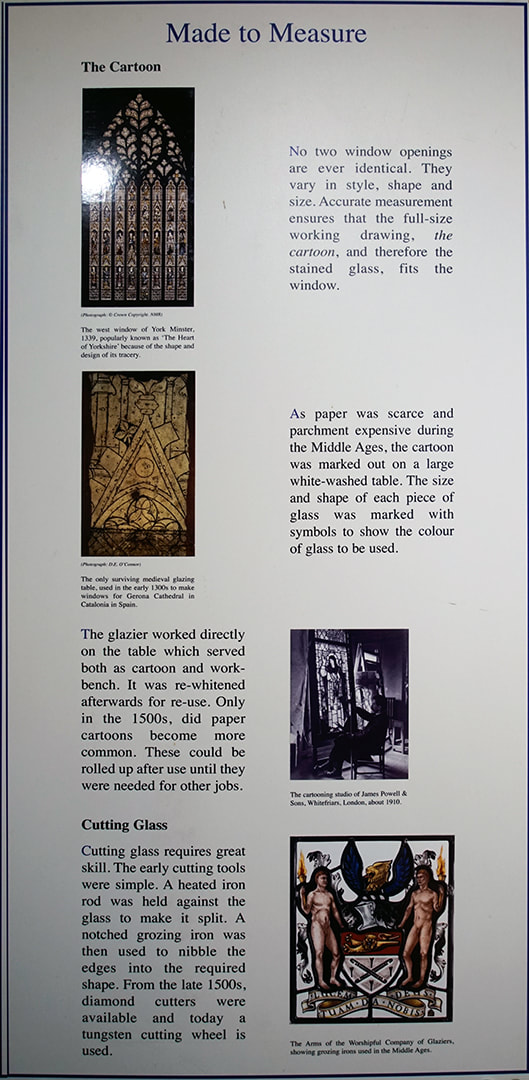

In 1847 he encouraged experiments designed to rediscover the chemical components of medieval glass and persuaded the London firm of James Powell $ Sons to make 'antique' glass to his recipes. . At the same time Pugin was encouraging similar experiments by the Birmingham firm of John Hardman.

A series of important restorations of medieval windows, including those in Bristol and Glouscester Cathedrals, gave stained glass artists valuable first-ham experience of old glass. By 1850, stained glass artists were at last able to obtain glass of a quality matching that of the Middle Ages.

A number of influential historical studies in 1840-50 gave craftsmen and designers invaluable information about the Middle Ages. The most important were by Charles Winston, a patent lawyer and amateur historian. His studies made him aware of the short-comings of the glass available to artist of his own day, which was often thin and garish in colour.

In 1847 he encouraged experiments designed to rediscover the chemical components of medieval glass and persuaded the London firm of James Powell $ Sons to make 'antique' glass to his recipes. . At the same time Pugin was encouraging similar experiments by the Birmingham firm of John Hardman.

A series of important restorations of medieval windows, including those in Bristol and Glouscester Cathedrals, gave stained glass artists valuable first-ham experience of old glass. By 1850, stained glass artists were at last able to obtain glass of a quality matching that of the Middle Ages.

A working Studio in the 19th century

The diversity of a firm's offering would include figures under canopies, memorial windows, coats of arms, ornamental stencilled windows, embossed and enamelled work, landscape windows for hall and stairways, and bent glass.

The diversity of a firm's offering would include figures under canopies, memorial windows, coats of arms, ornamental stencilled windows, embossed and enamelled work, landscape windows for hall and stairways, and bent glass.

Victorian Revival

The full extent of the revival of the Medieval style, known as Gothic Revival, was illustrated at the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851. One of the most spectacular displays was the Gothic Court where twenty-five stained glass studios exhibited. However, with the exception of the works by Pugin and Hardman, British works were generally considered inferior to the European exhibits. Windows based on a wide variety of different medieval styles were n display and a number of firms were still offering enamel glass-paintings in the 18th-century fashion.

A decade later the situation was transformed, windows based on the art of the 13th and early 14th centuries dominated the scene. This transformation had been brought about by a younger generation of architects. Under their enthusiastic influence, new stained glass studios were formed - Clayton & Bell, Heaton & Butler and Lavers & Barraud were all established in 1855. In terms of design and the quality of manufacture, British stained glass was now second to none.

The full extent of the revival of the Medieval style, known as Gothic Revival, was illustrated at the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851. One of the most spectacular displays was the Gothic Court where twenty-five stained glass studios exhibited. However, with the exception of the works by Pugin and Hardman, British works were generally considered inferior to the European exhibits. Windows based on a wide variety of different medieval styles were n display and a number of firms were still offering enamel glass-paintings in the 18th-century fashion.

A decade later the situation was transformed, windows based on the art of the 13th and early 14th centuries dominated the scene. This transformation had been brought about by a younger generation of architects. Under their enthusiastic influence, new stained glass studios were formed - Clayton & Bell, Heaton & Butler and Lavers & Barraud were all established in 1855. In terms of design and the quality of manufacture, British stained glass was now second to none.

Scottish Glass

Scotland had now surviving stained-glass tradition to pass on to its artists of the 19th century. Religious strife, neglect and a gradual loss of skill in the craft resulted over a period of 250 years in the virtual elimination of medieval stained glass from Scotland.

A revival began relatively late in the 19th century and from the outset, Scottish artists were far more responsive to Continental Art Nouveau than their English counterparts. By the 1890s, Glasgow had emerged as Scoltland's foremost city of art.

Daniel Cottier and then Charles Rennie Mackintosh were artist with international regulations and an influence that extended beyond Scotland's borders. The firm of J & W Guthrie employed a succession of talented freelance designers who produced exciting and distinctive stained glass. Two of the most highly regarded artists are David Gault and J. Harrington Mann.

Scotland had now surviving stained-glass tradition to pass on to its artists of the 19th century. Religious strife, neglect and a gradual loss of skill in the craft resulted over a period of 250 years in the virtual elimination of medieval stained glass from Scotland.

A revival began relatively late in the 19th century and from the outset, Scottish artists were far more responsive to Continental Art Nouveau than their English counterparts. By the 1890s, Glasgow had emerged as Scoltland's foremost city of art.

Daniel Cottier and then Charles Rennie Mackintosh were artist with international regulations and an influence that extended beyond Scotland's borders. The firm of J & W Guthrie employed a succession of talented freelance designers who produced exciting and distinctive stained glass. Two of the most highly regarded artists are David Gault and J. Harrington Mann.

Growing Stylistic Freedom

From about 1870, artists felt much more freedom to experiement with new styles. Japanese art arrived in the West, intoducing an exotic element to European design. The established Victorian studios continued to work in Gothic style, but a number of influential free-lance designers, including Harry Ellis Wooldridge and Henry Holiday, began to transform the work of the older studios.

Holiday's work introduced more natural figure drawing and brought back the sculptural styles of Greece, Rome and 15-16th century Italy to the firm of James Powell & Sons and Lavers & Barraud. The painting of the 15th and early 16th centuries in the Netherlands and in Germany influenced the firms of Charles Earner Kempe and Burlison & Grylls. Their windows make more use of white glass and yellow stain and a far lighter painting style.

Following a period in which stained glass had slavishly copied the art of the medieval past, artists were now free from these limitations in the style of their work.

From about 1870, artists felt much more freedom to experiement with new styles. Japanese art arrived in the West, intoducing an exotic element to European design. The established Victorian studios continued to work in Gothic style, but a number of influential free-lance designers, including Harry Ellis Wooldridge and Henry Holiday, began to transform the work of the older studios.

Holiday's work introduced more natural figure drawing and brought back the sculptural styles of Greece, Rome and 15-16th century Italy to the firm of James Powell & Sons and Lavers & Barraud. The painting of the 15th and early 16th centuries in the Netherlands and in Germany influenced the firms of Charles Earner Kempe and Burlison & Grylls. Their windows make more use of white glass and yellow stain and a far lighter painting style.

Following a period in which stained glass had slavishly copied the art of the medieval past, artists were now free from these limitations in the style of their work.

William Morris & his Circle

William Morris and Edward Burn-Jones were two of the most influential figures in Victorian art and design who met as theological students in Oxford in the 1850s. They gave up their plans to enter the Church and took up art instead. In 1861, in partnership with artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Made Brown, the architect Philip Webb and others, they established the firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Company.

Although the firm made furniture, tiles and textiles, stained glass was always an important part of their output. A subtile and original approach to colour and a fresh approach to design characterized their work. Their windows evolved the romance and pageantry of the Middle Ages.

In the mid-170s, Burn-Jones became the firm's chief designer. His work was increasingly influenced by Italian Renaissance art. This was combined with Morris's genius for pattern, familiar in this designs for wallpaper and textiles and in the colourful rich foliage in the glass in the firm's windows. Some of their finest work can still seen at Jesus College and Peterhouse in Cambridge.

William Morris and Edward Burn-Jones were two of the most influential figures in Victorian art and design who met as theological students in Oxford in the 1850s. They gave up their plans to enter the Church and took up art instead. In 1861, in partnership with artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Made Brown, the architect Philip Webb and others, they established the firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Company.

Although the firm made furniture, tiles and textiles, stained glass was always an important part of their output. A subtile and original approach to colour and a fresh approach to design characterized their work. Their windows evolved the romance and pageantry of the Middle Ages.

In the mid-170s, Burn-Jones became the firm's chief designer. His work was increasingly influenced by Italian Renaissance art. This was combined with Morris's genius for pattern, familiar in this designs for wallpaper and textiles and in the colourful rich foliage in the glass in the firm's windows. Some of their finest work can still seen at Jesus College and Peterhouse in Cambridge.

The Arts and Crafts Movement

Although William Morris had seen the medieval artist-craftsman as an ideal, pressure for the firm to be profitable frustrated his efforts to copy medieval studio conditions. A younger generation of artists and craft-workers emerged in the 1890s - working independently in small-scale studios. In an industrial age, they were committed to 'honest' simple design. Their inspiration was often drawn from the ordinary object to be found in simple rural homes.

The stained glass artist and teacher, Christopher Hall, was a leading figure. His influential manual Stained Glass Work was published in 1905 and is still read and admired to this day.

Arts and Crafts stained glass is characterized by the quality and colour of the glass, the naturalistic figure style and canopy and border decoration inspired by the natural world.

Although William Morris had seen the medieval artist-craftsman as an ideal, pressure for the firm to be profitable frustrated his efforts to copy medieval studio conditions. A younger generation of artists and craft-workers emerged in the 1890s - working independently in small-scale studios. In an industrial age, they were committed to 'honest' simple design. Their inspiration was often drawn from the ordinary object to be found in simple rural homes.

The stained glass artist and teacher, Christopher Hall, was a leading figure. His influential manual Stained Glass Work was published in 1905 and is still read and admired to this day.

Arts and Crafts stained glass is characterized by the quality and colour of the glass, the naturalistic figure style and canopy and border decoration inspired by the natural world.

Slab Glass

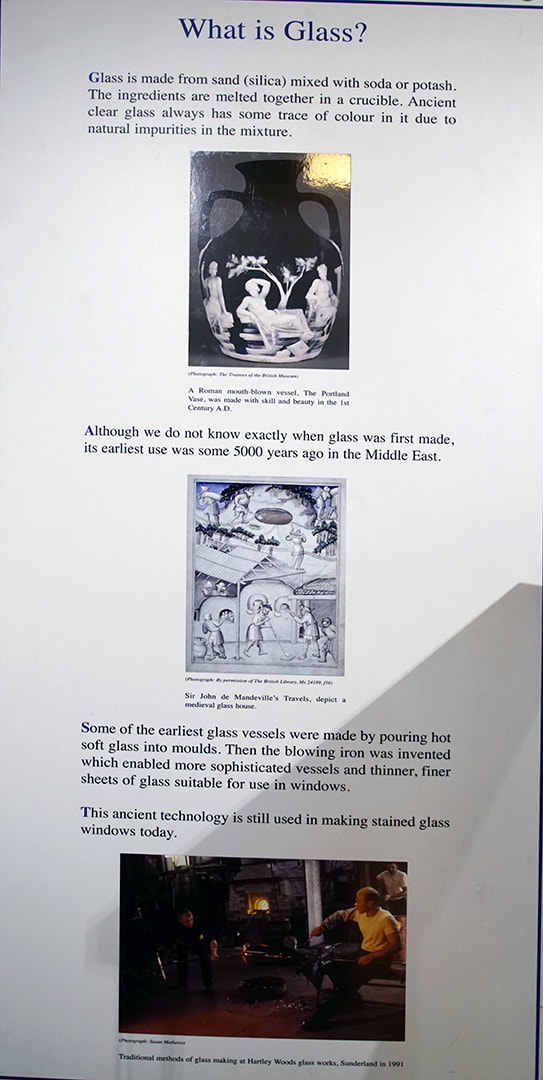

In 1889, the architect E.S. Prior encouraged the London glass firm of Britten and Gilson to make a new kind of glass for the windows he was designing and restoring. The glass was blown into a box-shaped mould, producing a five-sided rectangular bottle. Cutting the bottle along its edges produced five small sheets of uneven thickness.

Prior's Early English Slab soon had its imitators, and it was still being produced well into the 1940s. W. E Chance in Birmingham made Norman Slabs, as did James Powell & Sons of London and Hartley Woods of Sunderland.

Slab glass became closely associated with Arts and Crafts stained glass. Its very uneven thickness gives it colour of an exceptional intensity and a sparkling, jewel-like quality. Streaky and pale tinted slabs were used in contrast with sumptuous colour, including the distinctive gold pink made by adding gold dust to the molten glass mixture.

In 1889, the architect E.S. Prior encouraged the London glass firm of Britten and Gilson to make a new kind of glass for the windows he was designing and restoring. The glass was blown into a box-shaped mould, producing a five-sided rectangular bottle. Cutting the bottle along its edges produced five small sheets of uneven thickness.

Prior's Early English Slab soon had its imitators, and it was still being produced well into the 1940s. W. E Chance in Birmingham made Norman Slabs, as did James Powell & Sons of London and Hartley Woods of Sunderland.

Slab glass became closely associated with Arts and Crafts stained glass. Its very uneven thickness gives it colour of an exceptional intensity and a sparkling, jewel-like quality. Streaky and pale tinted slabs were used in contrast with sumptuous colour, including the distinctive gold pink made by adding gold dust to the molten glass mixture.

The Glass House

In 1897, the artist and compaigner for women's suffrage, Mary Lowndes, formed a partnership with craftsman Alfred Drury. In 1906, the firm of Lowndes & Drury moved to custom-built premises in Lettice Street in Fulham in London.

The Glass House, as it was known, became an inspirational centre for Arts and Crafts stained glass in Britain. Any freelance designer could rent one of the first-floor studios and make use of the workshop facilities and expertise of the staff. The company also stocked an enormous range and variety of glass. Victorian stained glass studiounswere usefully managed by men so the Glass House was especially encouraging to the growing number of talented women artists drawn to stained glass.

Among the artists represented in the Museum's collection, Karl Parsons, Henry Holiday, Margaret Aldrich Rope, Evie Hone, Moira Forsyth, Hugh Arnold, Francis Spear and Carl Edwards all worked at the Glass House. The last stained glass artists left Lettice Street in 1992.

In 1897, the artist and compaigner for women's suffrage, Mary Lowndes, formed a partnership with craftsman Alfred Drury. In 1906, the firm of Lowndes & Drury moved to custom-built premises in Lettice Street in Fulham in London.

The Glass House, as it was known, became an inspirational centre for Arts and Crafts stained glass in Britain. Any freelance designer could rent one of the first-floor studios and make use of the workshop facilities and expertise of the staff. The company also stocked an enormous range and variety of glass. Victorian stained glass studiounswere usefully managed by men so the Glass House was especially encouraging to the growing number of talented women artists drawn to stained glass.

Among the artists represented in the Museum's collection, Karl Parsons, Henry Holiday, Margaret Aldrich Rope, Evie Hone, Moira Forsyth, Hugh Arnold, Francis Spear and Carl Edwards all worked at the Glass House. The last stained glass artists left Lettice Street in 1992.

The Twentieth Century - Style and Influences

The early twentieth century was a time when many styles and influences converged. It was an era of unprecedented artistic diversity. In Ireland, the Celtic revival in arts and literature championed Irish folklore and language. In Britain, the Arts and Crafts movement followed in the footsteps of the pre-Raphaelites, espousing fine craftsmanship in the face of increased industrialization. In Europe he style of art nouveau placed importance on ornamentation and quality craftsmanship. In France, symbolism emerged as a highly imaginative art form, rooted in fantasy and imagination. In Vienna, the secessionists, including Klimt, experimented with highly decorative artworks. In the mid 1920s the international style for decorative arts became known as art deco, where elegance and functionality were espoused.

In the 1920s and 1930s, architects influenced by the Bauhaus in Germany and Frank Lloyd Wright in America, created a new architectural language that owed little to the styles of the past. Buildings of the modern movement were characterized by clean lines and an absence of surface decoration.

Large areas of glass combined with rhythmic lead-lines, and the acid-etching and sand blasting of plate glass, provided a cheaper method of glazing large areas, suitable for modern offices and commercial buildings. The use of painted decoration declined.

In France, use of dalles de verse became popular. Thick, cast slabs of glass unpainted but facetted with a tungsten hammer, were held in a web of epoxy resin or concrete. The best-known English examples are n Coventry and liverpool Metropolitan Cathedrals, designed by John Piper and made by Patrick Reyntiens.

Other noteworthy European artists have designed stained-glass windows, in both figurative and abstract veins, among them Chagall and Matisse (notably at Venice in the South of France). Trends in the United States appeared in the era when Louis Comfort Tiffany and John LaFarge were making radical technical innovations (See Stained Glass in the U.S.).

The early twentieth century was a time when many styles and influences converged. It was an era of unprecedented artistic diversity. In Ireland, the Celtic revival in arts and literature championed Irish folklore and language. In Britain, the Arts and Crafts movement followed in the footsteps of the pre-Raphaelites, espousing fine craftsmanship in the face of increased industrialization. In Europe he style of art nouveau placed importance on ornamentation and quality craftsmanship. In France, symbolism emerged as a highly imaginative art form, rooted in fantasy and imagination. In Vienna, the secessionists, including Klimt, experimented with highly decorative artworks. In the mid 1920s the international style for decorative arts became known as art deco, where elegance and functionality were espoused.

In the 1920s and 1930s, architects influenced by the Bauhaus in Germany and Frank Lloyd Wright in America, created a new architectural language that owed little to the styles of the past. Buildings of the modern movement were characterized by clean lines and an absence of surface decoration.

Large areas of glass combined with rhythmic lead-lines, and the acid-etching and sand blasting of plate glass, provided a cheaper method of glazing large areas, suitable for modern offices and commercial buildings. The use of painted decoration declined.

In France, use of dalles de verse became popular. Thick, cast slabs of glass unpainted but facetted with a tungsten hammer, were held in a web of epoxy resin or concrete. The best-known English examples are n Coventry and liverpool Metropolitan Cathedrals, designed by John Piper and made by Patrick Reyntiens.

Other noteworthy European artists have designed stained-glass windows, in both figurative and abstract veins, among them Chagall and Matisse (notably at Venice in the South of France). Trends in the United States appeared in the era when Louis Comfort Tiffany and John LaFarge were making radical technical innovations (See Stained Glass in the U.S.).

Title: Architectural Glass - Brookfield Court.

RN: A1-9867.

Location: Toronto.

Title: Architectural Glass - Brookfield Court.

RN: A1-9867.

Location: Toronto.

Architectural Glass - Printing on to glass with leading edge digital technology

Experimental techniques have also transformed approaches to the use of coloured glass in buildings. Double=glazing, artificial lighting and computer-generated design present new opportunities. New 2-D printers can etch designs in ceramic ink right onto giant panes of glass - company logos, artwork, really anything the creative mind can come up with.

Experimental techniques have also transformed approaches to the use of coloured glass in buildings. Double=glazing, artificial lighting and computer-generated design present new opportunities. New 2-D printers can etch designs in ceramic ink right onto giant panes of glass - company logos, artwork, really anything the creative mind can come up with.

Links

The J. Paul Getty Museum

Go to: www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/stained_glass/

Lamberts. The Glassmaking Company, Germany

Go to: www.lamberts.de/en/

Art History with Michelli

Go to: www.plinia.net

Go to: www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/stained_glass/

Lamberts. The Glassmaking Company, Germany

Go to: www.lamberts.de/en/

Art History with Michelli

Go to: www.plinia.net

19th - 20th Centuries

Ely Stained Glass Museum - Highlights from the Collection

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

Click to enlarge image.

Lacock Abbey, England

Photographic inventions

Lattice window at Lacock Abbey. In August 1835, a positive image of this window was taken by Henry Fox Talbot from what may be the oldest existing camera negative. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Fox_Talbot

Photographic inventions

Lattice window at Lacock Abbey. In August 1835, a positive image of this window was taken by Henry Fox Talbot from what may be the oldest existing camera negative. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Fox_Talbot

Click to enlarge image. Images for educational purposes only

Glass Heritage in France

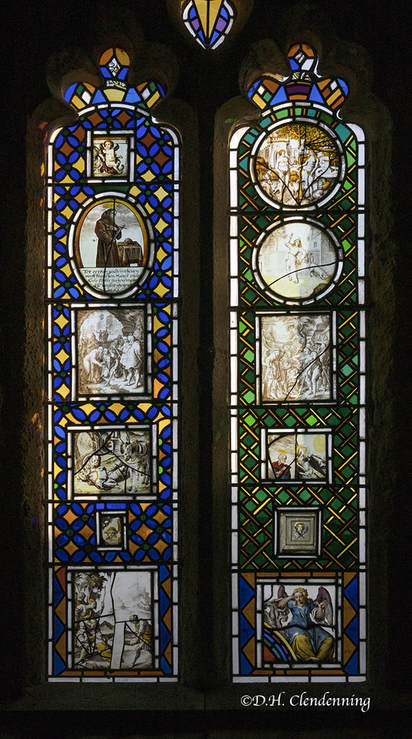

Glass from Germany

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) was a painter, printmaker, and theorist of the German Renaissance. Born in Nuremberg, Dürer established his reputation and influence across Europe when he was still in his twenties due to his high-quality woodcut prints. Wikipedia

Durer had his own glass workshop.

Durer had his own glass workshop.

Glass from Portugal & Spain

Glass in Switzerland

Glass from Sweden

Glass from New Zealand