Tiles Across Time

Islamic Tiles

Moorish Architecture - Andalusia at its Zenith

710-912 The Islamic Conquest

The Emirate of the Umayyad Family

Architecture of the 8th and 9th Centuries

The Foundation of the Great Mosque at Cordova

The Extension of the Friday Mosque

Seville and Merida

Bobastro

Vitality and Richness of Form

912-1031 A Golden Age: The Caliphate

Andalusia at its Zenith

Architecture of the 10th Century

Madinat al-Zahra

The Great Mosque of Cordova

Smaller Mosques

The Babita de Guardamar

Fortresses and Bridges

Towns: the Example of Vascos

Ornamentation

1031-1091 The Age of the Petty Kings

Architecture of the Taifa Period

Fortresses and Castles

The Aljaferia in Saragossa

Balaguer

Other Palaces and Works of Art

1091-1248 The Period of Berber Domination

Almoravid and Almohad Architecture

Almoravid Remains in North Africa and Andalusia

Murcia and Monteagudo

Crafts

New Directions in Religion and in Aesthetics

Seville, the Capital, and her Friday Mosque

Other Almohad Mosques in the South-Western Province

Palaces and Fortresses

Murcia Province: Cieza

Influences on the Christian North

1237-1492 The Rule of the Nasrids

Architectures of the Nasrids

The Alhambra: from Fortress to Palace City

Principal Architectural Themes of the Alhambra

Nasrid Architectural in the City and

Sultanate of Granada

Nasrid Architectural Ornamentation

The Emirate of the Umayyad Family

Architecture of the 8th and 9th Centuries

The Foundation of the Great Mosque at Cordova

The Extension of the Friday Mosque

Seville and Merida

Bobastro

Vitality and Richness of Form

912-1031 A Golden Age: The Caliphate

Andalusia at its Zenith

Architecture of the 10th Century

Madinat al-Zahra

The Great Mosque of Cordova

Smaller Mosques

The Babita de Guardamar

Fortresses and Bridges

Towns: the Example of Vascos

Ornamentation

1031-1091 The Age of the Petty Kings

Architecture of the Taifa Period

Fortresses and Castles

The Aljaferia in Saragossa

Balaguer

Other Palaces and Works of Art

1091-1248 The Period of Berber Domination

Almoravid and Almohad Architecture

Almoravid Remains in North Africa and Andalusia

Murcia and Monteagudo

Crafts

New Directions in Religion and in Aesthetics

Seville, the Capital, and her Friday Mosque

Other Almohad Mosques in the South-Western Province

Palaces and Fortresses

Murcia Province: Cieza

Influences on the Christian North

1237-1492 The Rule of the Nasrids

Architectures of the Nasrids

The Alhambra: from Fortress to Palace City

Principal Architectural Themes of the Alhambra

Nasrid Architectural in the City and

Sultanate of Granada

Nasrid Architectural Ornamentation

Islamic Geometric Design and Architectural Details

Madinat al-Zahra is located some five Kilometres to the north-west of Cordova. The job of site foreman, so to speak, was entrusted to the Crown Prince, the later Caliph al-Hakam 11.

|

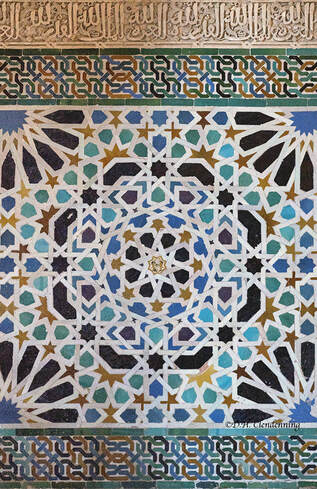

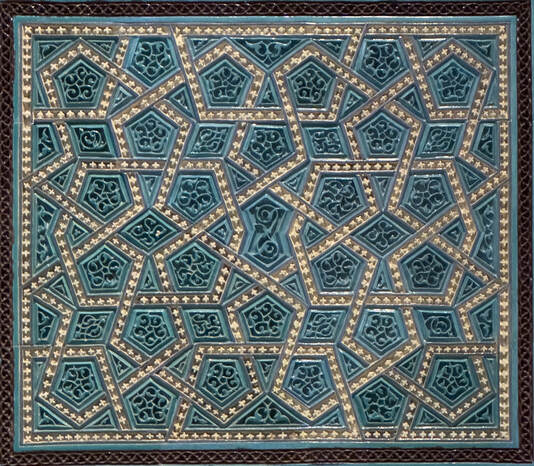

Prohibited by religious strictures from creating representational art, Muslim artists relied heavily on abstract patterns. Geometry, in particular, provided craftsmen with a fertile source of designs.

In the tile mosaic shown here, the artist started with the 12-pointed star in the centre of the panel, which is about five inches in diameter and is made of white tile inlaid with on continuous, delicately carved piece of black tile; it is regarded at the finest example of inlaid ceramic art in the Alhambra. By extending patterns from the star, the artist was able to generate the rest of his design, and by a careful arrangement of straight lines, he created figures that give the brilliant illustration of star shapes, circles and curves. LEFT: Detail of a glazed ceramic geometric composition from the Alhambra, Granada, Spain |

Mudejar Style Design in Andalusia Spain

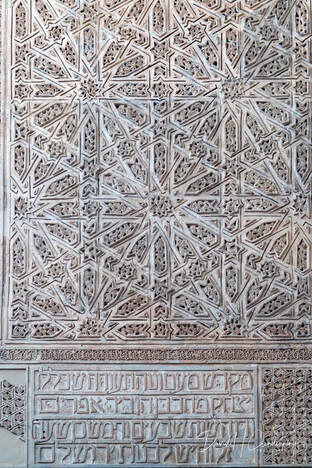

Cordoba Synagogue, c. 1315, is an historic edifice in the Jewish Quarter and it was decorated according to the best Mudejar tradition. It is the only synagogue in Cordoba to escape destruction during the years of persecution after the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. Although it now longer functions as a Jewish house of worship, it is open to the public.

|

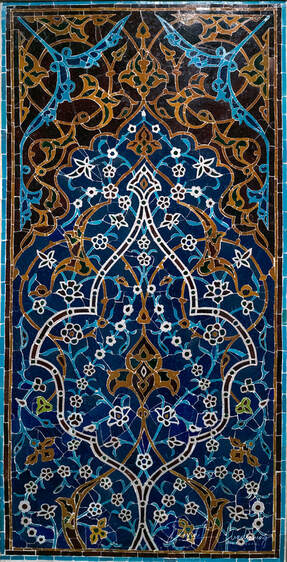

A Timurid tile panel (14th to 15th century) from Central Asia. The geometric composition has been skilfully designed, combining different sixfold patterns so that its design elements, such as the stars and hexagons, work together with the survey components in the tile panel.

|

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

Architectural Wall Tiles

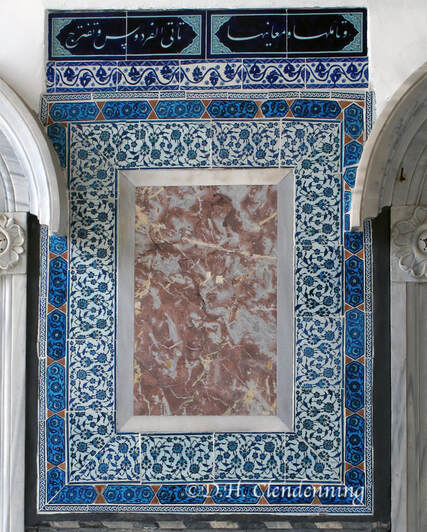

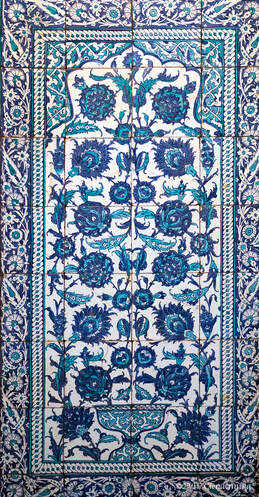

In the Middle East, tilework was originally developed as a decorative cladding for brick structures. By 1160, it was in use in Turkey, where tiles were later applied to stone buildings using mortar. The most accomplished type had colourful design painted on a brilliant white background. These were produced in the town of Iznik from about 1550.

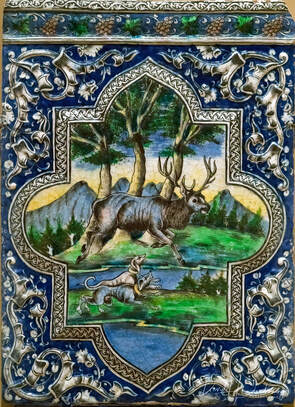

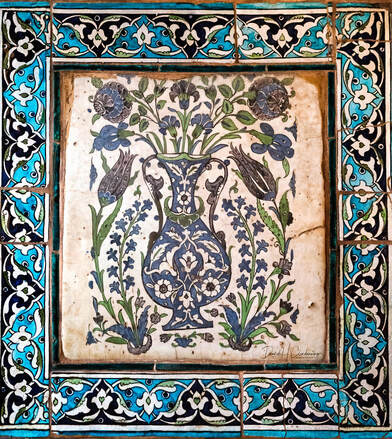

Wall Tiles from Turkey - Iznik style

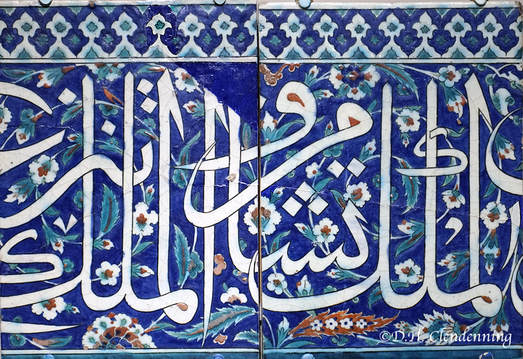

This panel of tiles may once have appeared over a door or window in an Istanbul palace or mosque. With its crisp and vividly coloured forms against a brilliant white background, its exemplifies the finest work made by Ottoman ceramicists in the town of Iznik, fifty miles from Istanbul.

CREATING THE COLOURS

Iznik potters made their colourful works using several key techniques. First, they created a white artificial clay and covered it with a thin layer of white slip to create a brilliant surface. Second, they developed a range of vividly coloured glazes and used contour lines to prevent them from running during firing. The deep blue was made from cobalt, probably mined in Iran, while the green came from copper filings. The coral red came from an iron-rich local clay called Armenian bole, it stands our in slight relief after firing, giving extra depth to forms in that colour.

CREATING THE COLOURS

Iznik potters made their colourful works using several key techniques. First, they created a white artificial clay and covered it with a thin layer of white slip to create a brilliant surface. Second, they developed a range of vividly coloured glazes and used contour lines to prevent them from running during firing. The deep blue was made from cobalt, probably mined in Iran, while the green came from copper filings. The coral red came from an iron-rich local clay called Armenian bole, it stands our in slight relief after firing, giving extra depth to forms in that colour.

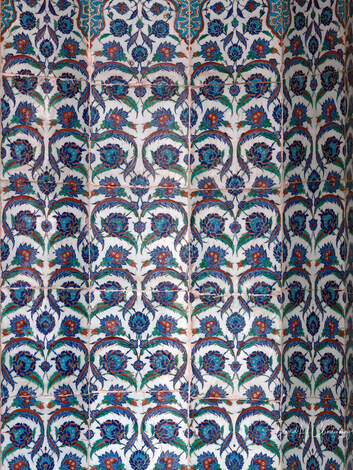

Iznik Tiles, Ottoman, Rusrem Pasa Cami (Mosque), 16th C, decorated famous floral and geometric tile designs, Istanbul

|

An illustrative book was produced for the exhibition on The Age of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, 25 January - 17 May 1987.

The reign of Sultan Suleyman 1 (1520-1566) marked the zenith of Ottoman political and economic power as well as the golden age of Turkish art and architecture. Suleyman was the tenth ruler of the house of Osman, the sultan who founded the Ottoman dynasty in northwestern Anatolia around 1300. Osman's descendants expanded into western Asia, eastern Europe, and northern Africa and established a powerful state. During his forty-six-year reign Suleyman double the territories of his realm, extending its boundaries from Iran to Austria. |

Title: Iznik Tile, Topkapi, 16th century.

Order No.: A1-0981

Title: Iznik Tile, Topkapi, 16th century.

Order No.: A1-0981

On the Tulip

The tulip is an exceptional flower that has accompanied the Turks during their migrations from Central Asia through to Anatolia, whence it has spread to Europe. This survivor adapts to every imaginable condition; it trives on arid rocky hillsides, mountains and meadows. Its distinctive, graceful lines make it perfectly suited to design and pattern creation, be it bud or full bloom. In the 16th century Ottoman art world, roses and tulips came to symbolize beauty and love. Wild tulips were domesticated into countless new cultivars, the vanguard of the tall and slender perfection that is the Ottoman 'Istanbul' tulip emerged, and names were conferred upon these new varieties.

The tulip is an exceptional flower that has accompanied the Turks during their migrations from Central Asia through to Anatolia, whence it has spread to Europe. This survivor adapts to every imaginable condition; it trives on arid rocky hillsides, mountains and meadows. Its distinctive, graceful lines make it perfectly suited to design and pattern creation, be it bud or full bloom. In the 16th century Ottoman art world, roses and tulips came to symbolize beauty and love. Wild tulips were domesticated into countless new cultivars, the vanguard of the tall and slender perfection that is the Ottoman 'Istanbul' tulip emerged, and names were conferred upon these new varieties.

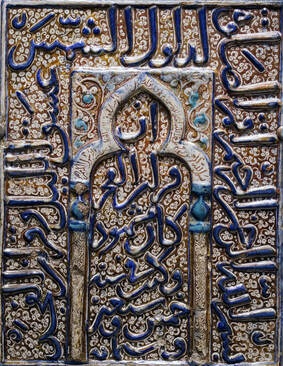

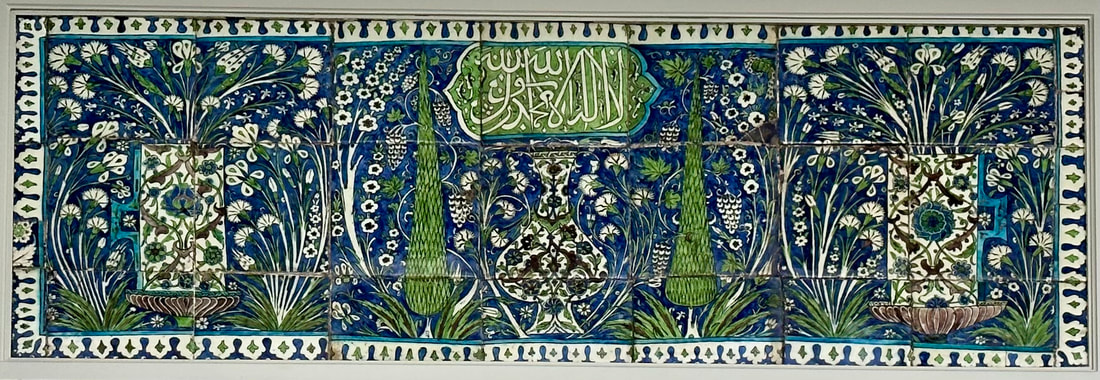

Syria - Damascus Tiles

The Ottoman Empire extended into Syria, where its artistic expressions were adopted. Syrian potters could not achieve the brilliant red of Iznik, but their designs were often more robust.

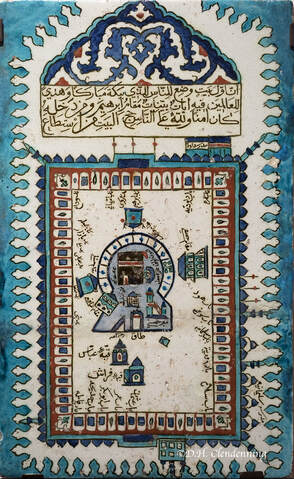

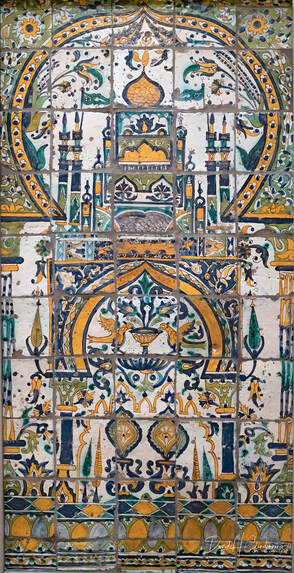

Tile panel: Syria (Damascus), about 1600. Fritware with polychrome decoration under transparent glaze.

Inside the arches on this tile panel appear hanging lamps like the glass on the right. They may symbolize God; the garden beyond the arches stands in for the garden paradise where the chosen will reside after Judgement Day. Arabic inscriptions make these sacred references clear: under the central arch one declares "Glory to God" and, at top and bottom, other name God, the Prophet Muhammad, and the first four leaders of Islam that succeeded Muhammad.

Inside the arches on this tile panel appear hanging lamps like the glass on the right. They may symbolize God; the garden beyond the arches stands in for the garden paradise where the chosen will reside after Judgement Day. Arabic inscriptions make these sacred references clear: under the central arch one declares "Glory to God" and, at top and bottom, other name God, the Prophet Muhammad, and the first four leaders of Islam that succeeded Muhammad.

Tunis - North Africa

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only