Roman Empire

Throughout history, Italy has been the heart of the action: epicentre of the Roman Empire, intellectual hub of the Renaissance, and destination for trade goods from the Silk Road.

Ancient Rome

Urbs kaput mundi - the city at the center of the world.

Beginning of the Roman Empire

Rome from legend to empire

According to legend, Rome was founded in 753 BC by Romulus, the first of seven kings. Over the next 250 years Rome grew from scattered huts into a city.

In 509 BC Rome became a republic, ruled by the Senate and people. By 200 BC, the republic had established control over the whole of Italy. In 146 BC it destroyed the powerful cities of Carthage in Tunisia, and Corinth in Greece - Rome now controlled the Mediterranean.

Looted Greek gold poured into Rome, but aristocrats competing for this wealth destabilized the republic, and civil war broke out. Julius Caesar re-established order, but was assassinated in 44 BC. His adopted son, Octavian, defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra of Egypt at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC and became ruler of the republic. In 27 BC Octavian renamed himself Augustus, and the Roman Empire was born.

In the new imperial order, Rome and Italy were at the centre of the empire. Roman Italy was bigger than modern Italy, and included parts of France, Switzerland, Austria, Croatia and Slovenia.

Italy is naturally divided into many regions by its landscape. Before the rise of Rome, these regions were inhabited by different peoples, for example, the Etruscans of central Italy or the Celts of the north. Rome conquered these regions, linking them with a network of roads. Towns were focal points, centres of commerce and the Roman administration.

Some areas, such as the Greek cities of southern Italy and Sicily, kept their distinctive identity. But overall, Rome succeeded in bringing Romanitas (Roman-ness) to Italy, with a shared language and central authority. Economically, Italy was the engine of the empire with Italian estates and workshops sending foodstuffs and finished good all over the Roman world.

The empire, stretching across the Mediterranean lands and most of Europe, lasted over 400 years. In AD 410 Rome was burnt by Germanic tribes and the last western emperor was deposed in AD 476. A century later Italy disintegrated and was not reunited until 1870. But the empire survived in the east, as the Byzantine Empire, until AD 1453.

According to legend, Rome was founded in 753 BC by Romulus, the first of seven kings. Over the next 250 years Rome grew from scattered huts into a city.

In 509 BC Rome became a republic, ruled by the Senate and people. By 200 BC, the republic had established control over the whole of Italy. In 146 BC it destroyed the powerful cities of Carthage in Tunisia, and Corinth in Greece - Rome now controlled the Mediterranean.

Looted Greek gold poured into Rome, but aristocrats competing for this wealth destabilized the republic, and civil war broke out. Julius Caesar re-established order, but was assassinated in 44 BC. His adopted son, Octavian, defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra of Egypt at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC and became ruler of the republic. In 27 BC Octavian renamed himself Augustus, and the Roman Empire was born.

In the new imperial order, Rome and Italy were at the centre of the empire. Roman Italy was bigger than modern Italy, and included parts of France, Switzerland, Austria, Croatia and Slovenia.

Italy is naturally divided into many regions by its landscape. Before the rise of Rome, these regions were inhabited by different peoples, for example, the Etruscans of central Italy or the Celts of the north. Rome conquered these regions, linking them with a network of roads. Towns were focal points, centres of commerce and the Roman administration.

Some areas, such as the Greek cities of southern Italy and Sicily, kept their distinctive identity. But overall, Rome succeeded in bringing Romanitas (Roman-ness) to Italy, with a shared language and central authority. Economically, Italy was the engine of the empire with Italian estates and workshops sending foodstuffs and finished good all over the Roman world.

The empire, stretching across the Mediterranean lands and most of Europe, lasted over 400 years. In AD 410 Rome was burnt by Germanic tribes and the last western emperor was deposed in AD 476. A century later Italy disintegrated and was not reunited until 1870. But the empire survived in the east, as the Byzantine Empire, until AD 1453.

Imperial Rome

Most of the visible remains of ancient Rome date from the time of the emperors. Images on coins and the impressive ruins of many of Rome's monuments give an idea of their original appearance.

Augustus was the first emperor. He and his supporters remodelled Rome, leaving a lasting legacy. They rebuilt the Roman forum, the religious, political and administrative hear of the city, as well as theatres, temples, baths, basilicas and porticoes. These monuments, built in the extravagant Corinthian style of architecture, pleased the people, beautified the city and glorified the emperor.

Later emperors also left their mark on the city. Claudius rebuilt the Circus Maximus, Nero built his enormous palace the Domus Area (Golden House), Vespasian erected the Colosseum, Trajan constructed an immense Forum and the Basilica Ullpia and Hadrian built the Pantheon, Several emperors including Titus, Caracalla, and Diocletian built lavish public baths.

Most of the visible remains of ancient Rome date from the time of the emperors. Images on coins and the impressive ruins of many of Rome's monuments give an idea of their original appearance.

Augustus was the first emperor. He and his supporters remodelled Rome, leaving a lasting legacy. They rebuilt the Roman forum, the religious, political and administrative hear of the city, as well as theatres, temples, baths, basilicas and porticoes. These monuments, built in the extravagant Corinthian style of architecture, pleased the people, beautified the city and glorified the emperor.

Later emperors also left their mark on the city. Claudius rebuilt the Circus Maximus, Nero built his enormous palace the Domus Area (Golden House), Vespasian erected the Colosseum, Trajan constructed an immense Forum and the Basilica Ullpia and Hadrian built the Pantheon, Several emperors including Titus, Caracalla, and Diocletian built lavish public baths.

|

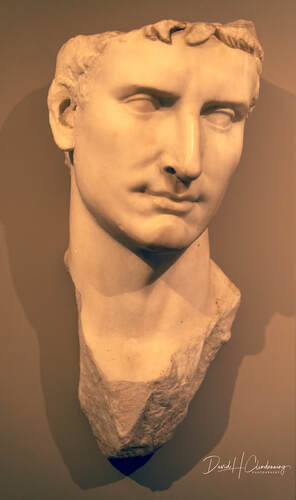

Augustus Caesar – Reigned 27 BC – 14 AD

While Julius Caesar set up the markings of a great empire, it was his great-nephew (and adopted son) who succeeded in implementing his dream. Born Gaius Octavius, Augustus Caesar formed the Second Triumvirate with Mark Antony and Marcus Lepidus, and when the Triumvirate separated the Republic into three divisions, Augustus gained great power and eventually founded the Roman Empire and became its first emperor. Augustus led the empire it its most prosperous period, doubling its size after defeating Cleopatra* and seizing Egypt. He also expanded the empire into Hungary, Croatia, Spain, and Gaul, and he was worshiped like a god amongst his people. *The death of Cleopatra ended the Hellenistic Age (323 - 31 BC) |

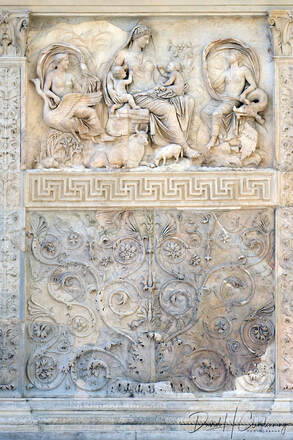

Altar of Augustus Peace in the Campus Martius

Title: Ara Pacis Frieze, Rome.

Order No.: A1-1452.

Title: Ara Pacis Frieze, Rome.

Order No.: A1-1452.

Ara Pacis Augustae, Rome. 9 BC. Frieze showing fragments with Vegetal Spirals (lily, rose, bellflower and date plams)

Augustus boasted that he found Rome a city of brick and left it of marble.

The Arch of Tiberius ("'Arcus Tiberi'") was a triumphal arch built in 16 AD in the ForumRomanum to celebrate the recovery of the eagle standards that had been lost to Germanic tribes by Varus in 9. The Roman general Germanicus had recovered the standards in 15 or 16.

|

The Arch of Titus (Italian: Arco di Tito; Latin: Arcus Titi) is a 1st-century AD honorific arch, located on the Via Sacra, Rome, just to the south-east of the Roman Forum. It was constructed in c. 81 AD by the Emperor Domitian shortly after the death of his older brother Titus to commemorate Titus's official deification or consecratio and the victory of Titus together with their father, Vespasian, over the Jewish rebellion in Judaea.The arch contains panels depicting the triumphal procession celebrated in 71 AD after the Roman victory culminating in the fall of Jerusalem,and provides one of the few contemporary depictions of artifacts of Herod's Temple. It became a symbol of the Jewish diaspora, and the menorah depicted on the arch served as the model for the menorah used as the emblem of the state of Israel.

The arch has provided the general model for many triumphal arches erected since the 16th century—perhaps most famously it is the inspiration for the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, France. |

Trajan's Column is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, that commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision of the architect Apollodorus of Damascus at the order of the Roman Senate.

Commemorating the dead

The Romans used facings of marble, terracotta and painted plaster to decorate not only public buildings and private homes but also tombs - the comes of the dead. Sculptures and inscriptions were central to these tombs. They showed the decreased and gave their name, family history and often their occupation.

Tombs were always sited away from where people lived, often along roads or in a special 'city of the dead' or necropolis. Tombs were sacred places, tended by relatives of the dead and protected by Roman law.

Tombs were always sited away from where people lived, often along roads or in a special 'city of the dead' or necropolis. Tombs were sacred places, tended by relatives of the dead and protected by Roman law.

This in one of the earliest reliefs to commemorate the legitimate marriage of former slaves. The couple are shown as Roman citizens, a dramatic illustration of their rise in wealth and status following the grant of their freedom.

|

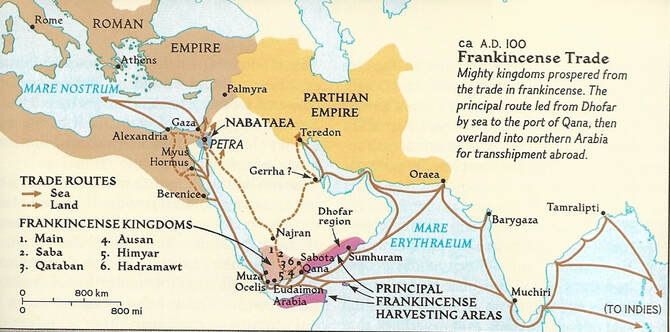

Early Trade Routes - Frankincense - AD 100

|

Iran - Persia

|

Palmyra and the Silk Road in the early Middle Ages

The ancient caravan city of Palmyra was a Roman provincial capital, which was an important trade centre on the Silk Road strategically situated between east and west connecting the Chinese, Persian and Roman empires. Merchants coming to or returning from Rome had to stop in Palmyra to pay taxes and simply to rest. Since around the year 227 AD, however, trade had been halted at intervals by the Sassanid Persians who periodically blocked the route to exact tribute. Silk had bee among the most popular commodities in Rome from before the time of Augustus (27 BC-14AD).

The World Between Empires – Rome and Partia

References from the Metropolitan Musuem of Art, New York City.

Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East

From the first century B.C. through the mid-third century A.D (100 B.C. – A.D. 250)., two superpowers defined the political map of the Middle East: The Roman Empire, with its base in the Mediterranean, and the Parthian Empire, which controlled Iran and much of Central Asia. The two empires competed over territories and trade routes across the Middle East, alternating between war and uneasy peace. Yet the region in which these events took place was distinct from both Rome and Iran, and its inhabitants had much in common with one another. They spoke related languages, traded along the same routes, and worshipped similar gods and goddesses. Their art draws from multiple traditions, expresses the complexity of their cultural, religious, and personal identities, and gives us a glimpse of ancient life at the meeting point of two empires.

The Middle East Between Rome and Parthia

The cultural histories of the cities along the ancient incense and silk trade routes that connect southwestern Arabia, Nabataea, Judaea, Syria, and Mesopotamia demonstrate how local life and culture were shaped by diverse cities and communities, and how identities were expressed through art.

The journey begins in southwestern Arabia, along caravan routes famous for incense and spices, then moves north along the eastern Mediterranean coast before ending in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), traveling through storied cities such as Petra, Jerusalem, Sidon, Baalbek, Palmyra, Hatra, and Babylon. Each had distinctive traditions, but they were also deeply interconnected, and their art often reveals the ways in which they influenced one another. This was a geographic area that formed the edge to the Parthian and Roman Empires but central to the political, economic, religious, and cultural life of both.

Themes shared across the regions: images of gods and goddesses, portraits of people, valuable commodities such as incense and textiles, luxury vessels for banqueting, and armour for war, all set against the backdrop of global trading networks and the struggle between the Roman and Parthian Empires for regional control. Rome, in the west, aimed to enhance its wealth through eastward expansion, while Parthia, in the east, sought to protect the western half of its empire against Roman incursions.

In terms modern states, this journey begins in Yemen, continues north across Saudi Arabia to Jordan, through Israel and the Palestinian territories, to Lebanon, east across Syria, and finally south and east through Iraq.

Southwestern Arabia

Frankincense, the fragrant resin offered to gods and burned in temples, palaces, and private housed across the ancient world, was harvested in southwestern Arabia and transported north by camel caravans, along with myrrh, spices, and other commodities that came via Indian Ocean trade

The kingdoms of southwestern Arabia were never conquered by either the Roman or the Parthian Empire and were separated by desert from both. However, commercial ties to the two empires were strong. Prosperity from the incense trade led to flourishing artistic traditions that encompassed abstract and cuboid forms alongside elaborated Hellenistic-style figures. Funerary and religious sculptures were carved in translucent calcite alabaster or cast in bronze. Each kingdom’s religious pantheon was distinct, and similar celestial or animal symbols were used to evoke different deities in different kingdoms.

Nabataea

Nabataea, the destination of many of the Arabian caravans, was a major commercial power that established far-reaching connections from its capital at Petra.

Petra, in present-day Jordan, was the capital of the kingdom of Nabataea. The city was built among steep hills, and its dramatic setting is marked by hundreds of tombs carved into the red sandstone cliffs.

Nabataean art included dramatic Hellenistic imagery alongside stylized and aniconic Arabian forms. Large temples dedicated to Nabataean gods and goddesses lined a colonnaded main street in Petra’s center. Sculptures of these deities reflect multiple religious and artistic traditions: Graeco-Roman-style busts were created alongside highly schematic images of gods. The actual cult images inside the temples were frequently plain stones, called baetyls.

Nabataea’s wealth was gained through control of the trade of incense, spices, and other good brought by caravans from southwestern Arabia that continued onward to the Mediterranean coast and overland across Syria. Sophisticated water engineering allowed Petra to thrive despite its desert location, bringing water from several miles away for the gardens, fountains, and pools that surrounded temples and palaces, as well as for drinking and agriculture.

Judaea

In neighbouring Judaea, the predominantly Jewish population struggled for political independence and religious freedom against the constraints of Roman rule. One source of tension was the cult of the divine Roman emperor, which for polytheists did not compromise existing religious practice, since the new cult could simply be added to the pantheon, but for monotheist created a fundamental conflict.

Some of the most serious rebellions against Roman rule occurred in Jerusalem in the province of Judaea, and the evocative imagery that developed around Jewish resistance to Rome continues to resonate today.

The Roman province was formed from the client kingdom of Judaea, ruled by Herod the Great (. 37-4 B.C.) and his descendants, and kingdoms to the north and south. The province proved difficult for Rome to control, with religious practices among the causes of conflict. In particular, the Roman requirement that subjects of the empire participate in the imperial cult-the worship of the emperor as a god- contradicted the core tenets of Judaism.

The First Roman-Jewish War, or Great Revolt, in 66-73/74 led to the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. Another major revolt, known as the Bar Kokhba rebellion (132-35) was supressed by the emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138), who expelled the Jewish population from Jerusalem and merged Judaea with the province of Syria to form a new province, Syria-Palaestina.

Tyre and Sidon

Sidon and Tyre, along with other cities along the Phoenician coast, were busy port that connected the trade routes of the Middle East with those that crossed the Mediterranean Sea. In additions, these cities were major centres of craft production:

Expensive purple dye, luxury clothing, perfumes, and cosmetics were at the core of Tyre and Sidon’s prosperity during the Roman period.

The thriving Phoenician cities along the eastern Mediterranean coast also exported cedar, olive oil, wheat, and wine, and they imported linen, jewels, and silk. Both had been major ports for many centuries, but their maritime trade was now enhanced by harbors greatly expanded wit concrete breakwaters built using Roman engineering techniques.

Sidon was renowned as a bronzeworking centre. Sidon was famed as the home of the greatest glassworkers of the age, most notably Ennion. Luxury glass vessels were produced at multiple cities in the eastern Mediterranean, but Sidon’s sand was reputedly the best quality for glassmaking. Its name carried a particular cachet: several ancient glassmakers identify themselves as “Sidonian” in signatures on their vessels. Funerary monuments from Tyre and Sidon combine local trends and Roman influences, expressing both strong civic identities and connections to the wider world.

Heliopolis-Baalbek

Worshippers travelled to the colossal sanctuary of Heliopolis-Baalbek devoted to the cult of Jupiter Heliopolitanus, a god who combined divine features from multiple Roman and Middle Eastern religious traditions, in the Beqaa Valley in present-day Lebanon, to offer dedications to the god Jupiter Heliopolitanus, to consult his oracle, and to celebrate festivals.

Jupiter Heliopolitanus was a powerful god of agriculture and the cosmos. His appearance is revealed by bronze and stone sculptures that are probably small-scale versions of the cult statue that originally stood in his main temple. His consort, Venus Heliopoltana, shown seated on a throne flanked by sphinxes, resembles the ancient Phoenician goddess Astarte. A third god, Mercury Heliopolitanus, was a protector of flocks.

The sanctuary was built in stages between the late first century B.C. and the early third century A.D. Its innovative design combined Graeco-Roman features, such as Corinthian column capitals, with distinctively Middle Eastern elements, including bull and lion protomes. Many of the worshippers and priest were descended from Roman military veterans who settled at Heliopolis when it became part of the newly established colony of Berytus (Beirut) in 15 B.C. The Roman emperor, Trajan (r. 98-117) famously received a prediction of his death from the sanctuary’s oracle.

Palmyra

To the east in the Syrian Desert, the prominent oasis city of Palmyra played a critical role at the western end of routes that for the first time connected the region to China, forming what would become the early Silk Road. The cosmopolitan oasis city of Palmyra gained immense wealth by levying tariffs on silk and other goods in return for protecting caravans crossing the Syrian Desert. Palmyra’s wealth was reflected in its lavish temples, tombs and sculptures.

Palmyra maintained a highly distinctive local identity despite being annexed by the Roman Empire, most likely in the first century A.D. A powerful elite dominated commercial, civic, and religious life, and these families were commemorated in lavish tombs on the city’s outskirts, where their funerary portraits were displayed. They financed the construction of civic monuments and sanctuaries, including the most important one, the Temple of Bel, and served as priests responsible for the rituals and banquets that were central to Palmyrene life.

Palmyra’s deities were unique to the city: some were specifically local, while others were adapted from Mesopotamian, Arabian, and Phoenician gods. Their representations in sculpture reveal the multifaceted cultural identities of the people who worshipped them.

Queen Zenobia and Palmyra’s Bid for Empire

In the third century Palmyra briefly created an empire of its own. At a time when Roman power in the Middle East was weakened by recent military defeats, the Palmyrene queen Zenobia, acting as regent for her son Vaballathus (r. 267-272), greatly expanded the territory under Palmyra’s control, and in 270 she launched a campaign that brought central Anatolia and even Egypt under Palmyrene rule. However, Palmyra’s imperial expansion coincided with a return of Roman military strength under the emperor Aurelian (r. 270-275), who campaigned across Anatolia and Syria to restore Rome’s lost territory. Zenobia was forced to flee and Aurelian captured Palmyra, restoring Rome’s eastern empire. Zenobia and Valballathus were eventually captured, but their subsequent fates are uncertain: accounts range from execution to long lives in comfortable exile. Zenobia’s story has inspired a range of legends, an opera, and representations in art antiquity to the present.

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq, was strategically critical to the Parthian Empire. Located near the frontier with Rome and agriculturally rich, it also formed the meeting point of overland and maritime trade networks.

The city of Hatra, dominated by a giant temple complex, was an important religious centre and effectively controlled commerce along a major route. When necessary, it also served as a Parthian bulwark against Roman military campaigns. Ctesiphon, a city on the Tigris River in Central Mesopotamia, was the main royal residence of the Parthian kings. Elsewhere, temples that had functioned for thousands of years in cities such as Babylon entered their final phases. The last texts written n cuneiform script were produced in their libraries, and images of their gods and goddesses changed as they incorporated Graeco-Roman forms.

Dura-Europos

Further east, on the bank of the Euphrates River that frequently formed the border between the tow empires, the settlement of Dur-Europos underwent a transformation from a Parthian regional capital into a Roman military frontier outpost, characterized by religouos and cultural diversity.

Dura-Europos, in eastern Syria, provides a vivid picture of how diverse religious communities coexisted in an ancient Middle Eastern town.

Polytheistic and monotheistic religions were practised alongside one another, as the wall paintings, sculptures of gods, and ceiling tiles illustrate. A house repurposed in about the 232 as a space for Christian worship is considered the world’s oldest surviving church, and its decoration included the earliest known images of Jesus. The city’s synagogue, also dated to the third century, is famous for wall paintings depicting biblical scenes. Both building were located near multiple temples where many deities of different origins were worshipped in the form of cult statues or reliefs.

The city was located on the Euphrates River at the border of the Roman and Parthian Empires. It was a regional capital under Parthian control for more than two centuries until around the year 165, when the Roman Empire gained control of the area and the city became a Roman military outpost. Archeological excavations in the 1920s and 1930s uncovered at least nineteen religious buildings, as well as a military camp, baths, and more than one hundred houses.

At Ashur, the central courtyard of a large Parthian palace was decorated extensively with false windows and half-columns and with numerous stucco (fine plaster) panels, originally painted in bright colours. Each wall of the courtyard centered on an iwan, a large vaulted portico leading into a wing of the palace. The use of the iwan began during the Parthian period, and the courtyard at Ashur is among the earliest examples of a design-four iwans arranged around a central courtyard-that would later become an important feature of Islamic architecture. The facades were decorated with stucco moldings and panels with elaborate three-dimensional geometric, floral, and sometimes figural designs. This form of decoration is also seen in Sasanian and Islamic architecture.

Changing Times: The Rise of the Sasanian Empire

Enormous political changes took place in the Middle East during the third century as a new empire emerged.

Ardashir 1 (r. ca. 224-241), a local ruler of the region of Tersis (Pars) in southern Iran, overthrew the last Parthian kings and established the Sasanian Empire. His son, Shapur 1 (r. ca. 242-271), almost drove Rome out of the Middle East. In conflicts with a series of Roman emperors, Shapur defeated Roman armies and exacted steep tributes in exchange for peace, culminating in his capture of the emperor Valerian (r. 253-260) in battle, the only time a Roman emperor had ever been taken prisoner. It was an event of great symbolic importance to both empires. These events were celebrated in Shapur’s propaganda, including depictions in rock-cut reliefs on cliffs in Iran. From this point forward, the Sasanian and Roman Empires began a new struggle for control in the Middle East.

Excavations at Ctesiphon show bricks decorated with grapevine motifs drawn originally from Dionysiac imagery, and the same motif continued in Sasanian art. Sasanian 6th century stuccos from Ctesiphon show the legacy of Parthian-period design with wall decoration with geometric and vegetal designs. Similar stucco designs are seen at the theatre at Babylon. By the Sasanian period motifs of grapes leaves, and vines were probably associated with Zoroastrian concepts of abundance, balance in nature, and seasonal regeneration, and no longer with Dionysos.

In recent years, three of the modern countries in this region Iraq, Syria, and Yemen have experienced damage to archaeological sites and museums in the context of war.

References from the Metropolitan Musuem of Art, New York City.

Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East

From the first century B.C. through the mid-third century A.D (100 B.C. – A.D. 250)., two superpowers defined the political map of the Middle East: The Roman Empire, with its base in the Mediterranean, and the Parthian Empire, which controlled Iran and much of Central Asia. The two empires competed over territories and trade routes across the Middle East, alternating between war and uneasy peace. Yet the region in which these events took place was distinct from both Rome and Iran, and its inhabitants had much in common with one another. They spoke related languages, traded along the same routes, and worshipped similar gods and goddesses. Their art draws from multiple traditions, expresses the complexity of their cultural, religious, and personal identities, and gives us a glimpse of ancient life at the meeting point of two empires.

The Middle East Between Rome and Parthia

The cultural histories of the cities along the ancient incense and silk trade routes that connect southwestern Arabia, Nabataea, Judaea, Syria, and Mesopotamia demonstrate how local life and culture were shaped by diverse cities and communities, and how identities were expressed through art.

The journey begins in southwestern Arabia, along caravan routes famous for incense and spices, then moves north along the eastern Mediterranean coast before ending in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), traveling through storied cities such as Petra, Jerusalem, Sidon, Baalbek, Palmyra, Hatra, and Babylon. Each had distinctive traditions, but they were also deeply interconnected, and their art often reveals the ways in which they influenced one another. This was a geographic area that formed the edge to the Parthian and Roman Empires but central to the political, economic, religious, and cultural life of both.

Themes shared across the regions: images of gods and goddesses, portraits of people, valuable commodities such as incense and textiles, luxury vessels for banqueting, and armour for war, all set against the backdrop of global trading networks and the struggle between the Roman and Parthian Empires for regional control. Rome, in the west, aimed to enhance its wealth through eastward expansion, while Parthia, in the east, sought to protect the western half of its empire against Roman incursions.

In terms modern states, this journey begins in Yemen, continues north across Saudi Arabia to Jordan, through Israel and the Palestinian territories, to Lebanon, east across Syria, and finally south and east through Iraq.

Southwestern Arabia

Frankincense, the fragrant resin offered to gods and burned in temples, palaces, and private housed across the ancient world, was harvested in southwestern Arabia and transported north by camel caravans, along with myrrh, spices, and other commodities that came via Indian Ocean trade

The kingdoms of southwestern Arabia were never conquered by either the Roman or the Parthian Empire and were separated by desert from both. However, commercial ties to the two empires were strong. Prosperity from the incense trade led to flourishing artistic traditions that encompassed abstract and cuboid forms alongside elaborated Hellenistic-style figures. Funerary and religious sculptures were carved in translucent calcite alabaster or cast in bronze. Each kingdom’s religious pantheon was distinct, and similar celestial or animal symbols were used to evoke different deities in different kingdoms.

Nabataea

Nabataea, the destination of many of the Arabian caravans, was a major commercial power that established far-reaching connections from its capital at Petra.

Petra, in present-day Jordan, was the capital of the kingdom of Nabataea. The city was built among steep hills, and its dramatic setting is marked by hundreds of tombs carved into the red sandstone cliffs.

Nabataean art included dramatic Hellenistic imagery alongside stylized and aniconic Arabian forms. Large temples dedicated to Nabataean gods and goddesses lined a colonnaded main street in Petra’s center. Sculptures of these deities reflect multiple religious and artistic traditions: Graeco-Roman-style busts were created alongside highly schematic images of gods. The actual cult images inside the temples were frequently plain stones, called baetyls.

Nabataea’s wealth was gained through control of the trade of incense, spices, and other good brought by caravans from southwestern Arabia that continued onward to the Mediterranean coast and overland across Syria. Sophisticated water engineering allowed Petra to thrive despite its desert location, bringing water from several miles away for the gardens, fountains, and pools that surrounded temples and palaces, as well as for drinking and agriculture.

Judaea

In neighbouring Judaea, the predominantly Jewish population struggled for political independence and religious freedom against the constraints of Roman rule. One source of tension was the cult of the divine Roman emperor, which for polytheists did not compromise existing religious practice, since the new cult could simply be added to the pantheon, but for monotheist created a fundamental conflict.

Some of the most serious rebellions against Roman rule occurred in Jerusalem in the province of Judaea, and the evocative imagery that developed around Jewish resistance to Rome continues to resonate today.

The Roman province was formed from the client kingdom of Judaea, ruled by Herod the Great (. 37-4 B.C.) and his descendants, and kingdoms to the north and south. The province proved difficult for Rome to control, with religious practices among the causes of conflict. In particular, the Roman requirement that subjects of the empire participate in the imperial cult-the worship of the emperor as a god- contradicted the core tenets of Judaism.

The First Roman-Jewish War, or Great Revolt, in 66-73/74 led to the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. Another major revolt, known as the Bar Kokhba rebellion (132-35) was supressed by the emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138), who expelled the Jewish population from Jerusalem and merged Judaea with the province of Syria to form a new province, Syria-Palaestina.

Tyre and Sidon

Sidon and Tyre, along with other cities along the Phoenician coast, were busy port that connected the trade routes of the Middle East with those that crossed the Mediterranean Sea. In additions, these cities were major centres of craft production:

Expensive purple dye, luxury clothing, perfumes, and cosmetics were at the core of Tyre and Sidon’s prosperity during the Roman period.

The thriving Phoenician cities along the eastern Mediterranean coast also exported cedar, olive oil, wheat, and wine, and they imported linen, jewels, and silk. Both had been major ports for many centuries, but their maritime trade was now enhanced by harbors greatly expanded wit concrete breakwaters built using Roman engineering techniques.

Sidon was renowned as a bronzeworking centre. Sidon was famed as the home of the greatest glassworkers of the age, most notably Ennion. Luxury glass vessels were produced at multiple cities in the eastern Mediterranean, but Sidon’s sand was reputedly the best quality for glassmaking. Its name carried a particular cachet: several ancient glassmakers identify themselves as “Sidonian” in signatures on their vessels. Funerary monuments from Tyre and Sidon combine local trends and Roman influences, expressing both strong civic identities and connections to the wider world.

Heliopolis-Baalbek

Worshippers travelled to the colossal sanctuary of Heliopolis-Baalbek devoted to the cult of Jupiter Heliopolitanus, a god who combined divine features from multiple Roman and Middle Eastern religious traditions, in the Beqaa Valley in present-day Lebanon, to offer dedications to the god Jupiter Heliopolitanus, to consult his oracle, and to celebrate festivals.

Jupiter Heliopolitanus was a powerful god of agriculture and the cosmos. His appearance is revealed by bronze and stone sculptures that are probably small-scale versions of the cult statue that originally stood in his main temple. His consort, Venus Heliopoltana, shown seated on a throne flanked by sphinxes, resembles the ancient Phoenician goddess Astarte. A third god, Mercury Heliopolitanus, was a protector of flocks.

The sanctuary was built in stages between the late first century B.C. and the early third century A.D. Its innovative design combined Graeco-Roman features, such as Corinthian column capitals, with distinctively Middle Eastern elements, including bull and lion protomes. Many of the worshippers and priest were descended from Roman military veterans who settled at Heliopolis when it became part of the newly established colony of Berytus (Beirut) in 15 B.C. The Roman emperor, Trajan (r. 98-117) famously received a prediction of his death from the sanctuary’s oracle.

Palmyra

To the east in the Syrian Desert, the prominent oasis city of Palmyra played a critical role at the western end of routes that for the first time connected the region to China, forming what would become the early Silk Road. The cosmopolitan oasis city of Palmyra gained immense wealth by levying tariffs on silk and other goods in return for protecting caravans crossing the Syrian Desert. Palmyra’s wealth was reflected in its lavish temples, tombs and sculptures.

Palmyra maintained a highly distinctive local identity despite being annexed by the Roman Empire, most likely in the first century A.D. A powerful elite dominated commercial, civic, and religious life, and these families were commemorated in lavish tombs on the city’s outskirts, where their funerary portraits were displayed. They financed the construction of civic monuments and sanctuaries, including the most important one, the Temple of Bel, and served as priests responsible for the rituals and banquets that were central to Palmyrene life.

Palmyra’s deities were unique to the city: some were specifically local, while others were adapted from Mesopotamian, Arabian, and Phoenician gods. Their representations in sculpture reveal the multifaceted cultural identities of the people who worshipped them.

Queen Zenobia and Palmyra’s Bid for Empire

In the third century Palmyra briefly created an empire of its own. At a time when Roman power in the Middle East was weakened by recent military defeats, the Palmyrene queen Zenobia, acting as regent for her son Vaballathus (r. 267-272), greatly expanded the territory under Palmyra’s control, and in 270 she launched a campaign that brought central Anatolia and even Egypt under Palmyrene rule. However, Palmyra’s imperial expansion coincided with a return of Roman military strength under the emperor Aurelian (r. 270-275), who campaigned across Anatolia and Syria to restore Rome’s lost territory. Zenobia was forced to flee and Aurelian captured Palmyra, restoring Rome’s eastern empire. Zenobia and Valballathus were eventually captured, but their subsequent fates are uncertain: accounts range from execution to long lives in comfortable exile. Zenobia’s story has inspired a range of legends, an opera, and representations in art antiquity to the present.

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq, was strategically critical to the Parthian Empire. Located near the frontier with Rome and agriculturally rich, it also formed the meeting point of overland and maritime trade networks.

The city of Hatra, dominated by a giant temple complex, was an important religious centre and effectively controlled commerce along a major route. When necessary, it also served as a Parthian bulwark against Roman military campaigns. Ctesiphon, a city on the Tigris River in Central Mesopotamia, was the main royal residence of the Parthian kings. Elsewhere, temples that had functioned for thousands of years in cities such as Babylon entered their final phases. The last texts written n cuneiform script were produced in their libraries, and images of their gods and goddesses changed as they incorporated Graeco-Roman forms.

Dura-Europos

Further east, on the bank of the Euphrates River that frequently formed the border between the tow empires, the settlement of Dur-Europos underwent a transformation from a Parthian regional capital into a Roman military frontier outpost, characterized by religouos and cultural diversity.

Dura-Europos, in eastern Syria, provides a vivid picture of how diverse religious communities coexisted in an ancient Middle Eastern town.

Polytheistic and monotheistic religions were practised alongside one another, as the wall paintings, sculptures of gods, and ceiling tiles illustrate. A house repurposed in about the 232 as a space for Christian worship is considered the world’s oldest surviving church, and its decoration included the earliest known images of Jesus. The city’s synagogue, also dated to the third century, is famous for wall paintings depicting biblical scenes. Both building were located near multiple temples where many deities of different origins were worshipped in the form of cult statues or reliefs.

The city was located on the Euphrates River at the border of the Roman and Parthian Empires. It was a regional capital under Parthian control for more than two centuries until around the year 165, when the Roman Empire gained control of the area and the city became a Roman military outpost. Archeological excavations in the 1920s and 1930s uncovered at least nineteen religious buildings, as well as a military camp, baths, and more than one hundred houses.

At Ashur, the central courtyard of a large Parthian palace was decorated extensively with false windows and half-columns and with numerous stucco (fine plaster) panels, originally painted in bright colours. Each wall of the courtyard centered on an iwan, a large vaulted portico leading into a wing of the palace. The use of the iwan began during the Parthian period, and the courtyard at Ashur is among the earliest examples of a design-four iwans arranged around a central courtyard-that would later become an important feature of Islamic architecture. The facades were decorated with stucco moldings and panels with elaborate three-dimensional geometric, floral, and sometimes figural designs. This form of decoration is also seen in Sasanian and Islamic architecture.

Changing Times: The Rise of the Sasanian Empire

Enormous political changes took place in the Middle East during the third century as a new empire emerged.

Ardashir 1 (r. ca. 224-241), a local ruler of the region of Tersis (Pars) in southern Iran, overthrew the last Parthian kings and established the Sasanian Empire. His son, Shapur 1 (r. ca. 242-271), almost drove Rome out of the Middle East. In conflicts with a series of Roman emperors, Shapur defeated Roman armies and exacted steep tributes in exchange for peace, culminating in his capture of the emperor Valerian (r. 253-260) in battle, the only time a Roman emperor had ever been taken prisoner. It was an event of great symbolic importance to both empires. These events were celebrated in Shapur’s propaganda, including depictions in rock-cut reliefs on cliffs in Iran. From this point forward, the Sasanian and Roman Empires began a new struggle for control in the Middle East.

Excavations at Ctesiphon show bricks decorated with grapevine motifs drawn originally from Dionysiac imagery, and the same motif continued in Sasanian art. Sasanian 6th century stuccos from Ctesiphon show the legacy of Parthian-period design with wall decoration with geometric and vegetal designs. Similar stucco designs are seen at the theatre at Babylon. By the Sasanian period motifs of grapes leaves, and vines were probably associated with Zoroastrian concepts of abundance, balance in nature, and seasonal regeneration, and no longer with Dionysos.

In recent years, three of the modern countries in this region Iraq, Syria, and Yemen have experienced damage to archaeological sites and museums in the context of war.

Eastern Turkey

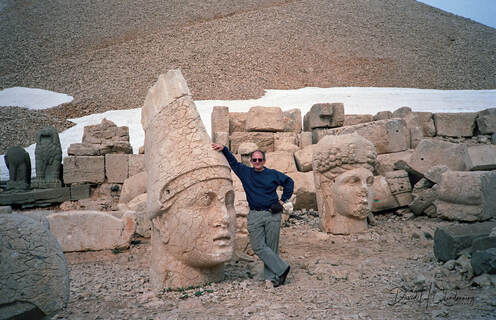

NEMRUT DAGI, TURKEY

The unique mountain top shrine was unknown to all but local herders until its discovery in1881 by a geologist in the employ of the Ottoman government. Archaeological excavations in 1953 by the American School of Oriental Research have conducted precise surveys of the site and instituted a preservation program but have provided little insight into the either the methods of construction or ancient use of the strange rock hill and its temples. History records that the kingdom of Commagene was situated on the border of the Seleucid Empire (which followed the empire of Alexander the Great in Anatolia) and the Parthian Empire. In 80 BC, with the Seleucid Empire weakening, the governor of Commagene declared his kingdom's independence. Soon thereafter, a Roman ally named Mithridates I Callinicus proclaimed himself king, set up his capital at Arsameia, and began the short-lived Commagene dynasty. Mithridates died in 64 BC and was succeeded by his son Antiochus I Epiphanes who ruled for 26 years. Commagene was thereafter ruled from Rome or by puppet kings until 72 AD when it was fully incorporated in the Roman Empire.

The unique mountain top shrine was unknown to all but local herders until its discovery in1881 by a geologist in the employ of the Ottoman government. Archaeological excavations in 1953 by the American School of Oriental Research have conducted precise surveys of the site and instituted a preservation program but have provided little insight into the either the methods of construction or ancient use of the strange rock hill and its temples. History records that the kingdom of Commagene was situated on the border of the Seleucid Empire (which followed the empire of Alexander the Great in Anatolia) and the Parthian Empire. In 80 BC, with the Seleucid Empire weakening, the governor of Commagene declared his kingdom's independence. Soon thereafter, a Roman ally named Mithridates I Callinicus proclaimed himself king, set up his capital at Arsameia, and began the short-lived Commagene dynasty. Mithridates died in 64 BC and was succeeded by his son Antiochus I Epiphanes who ruled for 26 years. Commagene was thereafter ruled from Rome or by puppet kings until 72 AD when it was fully incorporated in the Roman Empire.