The Byzantine World

The term "Byzantine Empire"

There was not such a contemporary institution as the Byzantine Empire. The term was invented by a German historian in the 17th century as a convenient method of differentiation between the Latin speaking Roman Empire and the latter Greek speaking Roman Empire.

The question arises whether "Byzantium" enables a Eurocentric western-oriented narrative about Greed, Rome, Europe, and the Renaissance that does not want to recognize classically educated, Greek-speaking, Orthodox Romans in the east.

There was not such a contemporary institution as the Byzantine Empire. The term was invented by a German historian in the 17th century as a convenient method of differentiation between the Latin speaking Roman Empire and the latter Greek speaking Roman Empire.

The question arises whether "Byzantium" enables a Eurocentric western-oriented narrative about Greed, Rome, Europe, and the Renaissance that does not want to recognize classically educated, Greek-speaking, Orthodox Romans in the east.

The rise and fall of the Byzantine Empire

Go to: ed.ted.com/lessons/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-byzantine-empire-leonora-neville

Go to: ed.ted.com/lessons/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-byzantine-empire-leonora-neville

Turkey the Centre of Byzantium

A historic crossroads of culture and design, Turkey's landscape provides a prominent display of its conquering empires, Greek, Roman, Byzantium and Ottoman.

A historic crossroads of culture and design, Turkey's landscape provides a prominent display of its conquering empires, Greek, Roman, Byzantium and Ottoman.

|

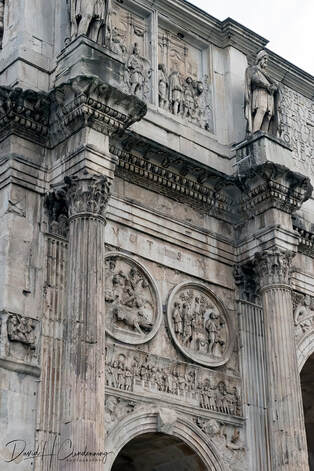

The Arch of Constantine (AD 312) is a triumphal arch in Rome dedicated to the emperor Constantine the Great. The arch was commissioned by the Roman Senate to commemorate Constantine’s victory over Maxentius at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in AD 312.

It is one of three surviving ancient Roman triumphal arches in Rome. Erected hastily to celebrate Constantine’s victory over Maxentius, it incorporates sculptures from many earlier buildings, including part of a battle frieze and figures of prisoners from the Forum of Trajan, a series of Hadrianic roundels, and a set of eight Aurelian panels. |

Christianity

Christianity became the dominant religion of the Roman Empire at the beginning of the fourth century, at about the same time the Roman Empire was divided into two separate but equal units: the Western Empire, with Rome as its administrative centre, and the Eastern Empire, with the ancient Greek city of Byzantium (later renamed Constantinople) as its capital and administrative centre.

Difference between the Eastern and Western Empires: Rome moved to backwater status in the fourth and fifth centuries. Milan supplanted Rome and then Ravenna became the third and final capital of the Western Roman Empire. This was necessitated due to the fact that the Emperor of the West was required at first to be close to the frontier dealing with the Barbarian invasions (i.e. Milan) and then in the fifth century to seek a stronger defence position in Ravenna.

The head of the Church in the East was next to the head of the Empire in Constantinople. But in the West, the head of the Church, the Bishop of Rome, never moved from Rome, even though the Western Emperor was later in residence in Milan and then in Ravenna. So Rome never lost its religious centricity. This in turn led to the development of the Papal estates following the collapse of the Western Empire itself under the weight of repeated and persistent attacks.

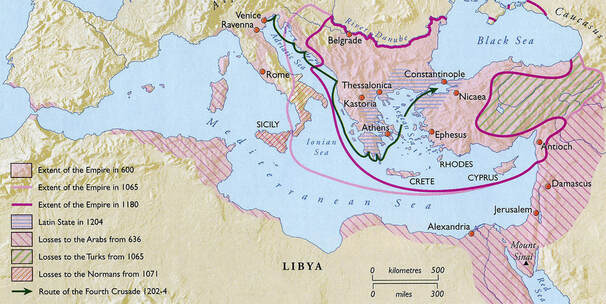

The Eastern Empire, by contrast, thrived. Constantinople assumed Rome's leading role in culture and art. Under its culture aegis, the peoples of the Hellenistic world and beyond became Christianized. Christian lands in the East included Greece, the Balkans, the Crimea and lands on the shores of the Black Sea, Asia Minor (today's Turkey), Palestine and Syria, Egypt and the Libyan coast, and the ancient land of Ethiopia, south of Egypt. The Eastern Church was divided for religious administrative purposes. Each division was ruled by a Patriarch, equal in status, with the Patriarch of Rome considered simply as "primus inter pares" ("a first among equals").

From the seventh century onward, many of these lands fell under Arabic rule, though Christians continued to live as a minority in these regions. Byzantium itself, however, continued to thrive and to convert new peoples in the north: the Slavs of the Balkans and Eastern Europe, who had arrived as invaders in the seventh century; the Bulgars, who settled in the area where Bulgaria is today; and the people of Ukraine and Russia, which included the Vikings, who had colonized the length of the Volga River and its Adjacent lands.

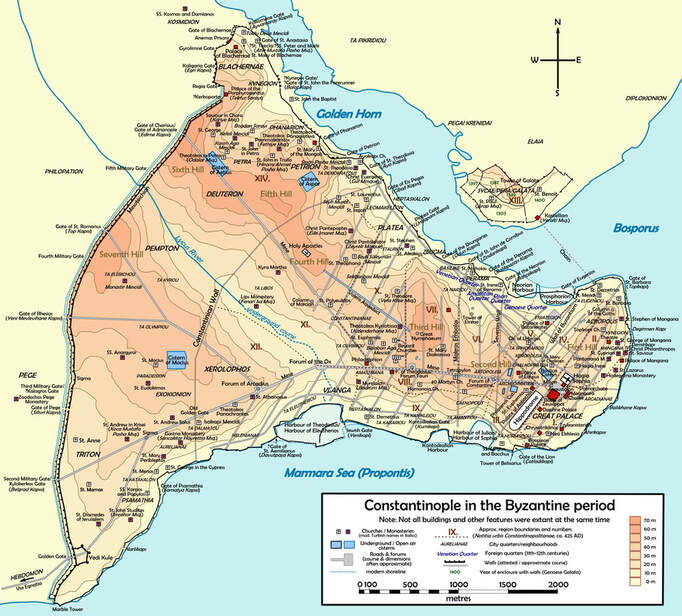

Constantinople remained the artistic, cultural and spiritual centre of all Orthodox Christians, even as they came under Islamic occupation. When, on May 29, 1453, Constantinople itself fell to the advancing armies of the Ottoman Turks, the Byzantine Empire came to an end. The Eastern Roman Empire had finally fallen after having continued the traditions of ancient Greece and Rome throughout more than a thousand years of shining cultural and artistic creation.

Difference between the Eastern and Western Empires: Rome moved to backwater status in the fourth and fifth centuries. Milan supplanted Rome and then Ravenna became the third and final capital of the Western Roman Empire. This was necessitated due to the fact that the Emperor of the West was required at first to be close to the frontier dealing with the Barbarian invasions (i.e. Milan) and then in the fifth century to seek a stronger defence position in Ravenna.

The head of the Church in the East was next to the head of the Empire in Constantinople. But in the West, the head of the Church, the Bishop of Rome, never moved from Rome, even though the Western Emperor was later in residence in Milan and then in Ravenna. So Rome never lost its religious centricity. This in turn led to the development of the Papal estates following the collapse of the Western Empire itself under the weight of repeated and persistent attacks.

The Eastern Empire, by contrast, thrived. Constantinople assumed Rome's leading role in culture and art. Under its culture aegis, the peoples of the Hellenistic world and beyond became Christianized. Christian lands in the East included Greece, the Balkans, the Crimea and lands on the shores of the Black Sea, Asia Minor (today's Turkey), Palestine and Syria, Egypt and the Libyan coast, and the ancient land of Ethiopia, south of Egypt. The Eastern Church was divided for religious administrative purposes. Each division was ruled by a Patriarch, equal in status, with the Patriarch of Rome considered simply as "primus inter pares" ("a first among equals").

From the seventh century onward, many of these lands fell under Arabic rule, though Christians continued to live as a minority in these regions. Byzantium itself, however, continued to thrive and to convert new peoples in the north: the Slavs of the Balkans and Eastern Europe, who had arrived as invaders in the seventh century; the Bulgars, who settled in the area where Bulgaria is today; and the people of Ukraine and Russia, which included the Vikings, who had colonized the length of the Volga River and its Adjacent lands.

Constantinople remained the artistic, cultural and spiritual centre of all Orthodox Christians, even as they came under Islamic occupation. When, on May 29, 1453, Constantinople itself fell to the advancing armies of the Ottoman Turks, the Byzantine Empire came to an end. The Eastern Roman Empire had finally fallen after having continued the traditions of ancient Greece and Rome throughout more than a thousand years of shining cultural and artistic creation.

|

Byzantine Coinage

|

The Byzantine Empire

|

Christian Church as the official Church of the Roman Empire

When one of the branches of the Christian Church became the official Church of the Roman Empire, the Emperor soon became its official head. He occupied a position as a sort of supreme patriarch among patriarchs, and supreme bishop among bishops. On 27 February 380, the Emperor Theodosius I formally established Nicene Christianity as the state church of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica. From now on, this one form of Christianity would be the sole permissible religion.

Justinian definitively established a system of church government, now called Caesaropapism, believing "he had the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the theological opinions to be held in the Church".

The Emperor exercised absolute control over the Church just as he exercised absolute control over the state, and it was not long before the arrangement was confirmed by declaring the Emperor to be infallible. For many centuries it was accepted Christian doctrine that the Emperor was the head of the Christian Church - Pontifex Maximus and Bishop of Bishops, that senior churchmen could be appointed by him, or at least appointed with his approval, that he alone convoked and presided over Universal Church Councils, that he enjoyed privileged direct communication with God, and that he was able to declare doctrine without reference to anyone else. Emperors such as Basiliscus, Zeno, Justinian I, Heraclius, and Constans II convoked councils to issue the edicts they had written, and in some cases they issued edicts themselves without reference to Church council or anyone else. The Emperor protected and favoured the Christian Church, and managed its administration. He not only appointed Patriarchs, but also set the territorial boundaries of their Patriarchies.

Justinian definitively established a system of church government, now called Caesaropapism, believing "he had the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the theological opinions to be held in the Church".

The Emperor exercised absolute control over the Church just as he exercised absolute control over the state, and it was not long before the arrangement was confirmed by declaring the Emperor to be infallible. For many centuries it was accepted Christian doctrine that the Emperor was the head of the Christian Church - Pontifex Maximus and Bishop of Bishops, that senior churchmen could be appointed by him, or at least appointed with his approval, that he alone convoked and presided over Universal Church Councils, that he enjoyed privileged direct communication with God, and that he was able to declare doctrine without reference to anyone else. Emperors such as Basiliscus, Zeno, Justinian I, Heraclius, and Constans II convoked councils to issue the edicts they had written, and in some cases they issued edicts themselves without reference to Church council or anyone else. The Emperor protected and favoured the Christian Church, and managed its administration. He not only appointed Patriarchs, but also set the territorial boundaries of their Patriarchies.

Hagia Sophia: Church of Divine Wisdom

Go to: www.thecollector.com/hagia-sophia-mosque/?utm_source=Flipboard&utm_medium=REFERRAL&utm_campaign=storyboards

Go to: www.thecollector.com/hagia-sophia-mosque/?utm_source=Flipboard&utm_medium=REFERRAL&utm_campaign=storyboards

The Importance of the Hagia Sophia and Recent Archeological Discoveries

Over the past 1500 years the Hagia Sophia has been a Greek Orthodox and Catholic cathedral, an Ottoman mosque, a museum and again now a mosque.

The Independent newspaper, in a January 2021 article, reported on recent archeological research that revealed the original design and subterranean mysteries of Europe's largest ancient landmark the former cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, which for almost a thousand years was the largest conventional building in the world.

The research has, for the first time, revealed the layout of the original sixth century cathedral complex and the existence of more than a kilometre of long-lost tunnels and subterranean chambers underneath the vast building.

The new discoveries are particularly important because, from a political and religious history perspective as well as an architectural one, Hagia Sophia is one of the most significant buildings in the world.

It was originally built to symbolise the establishment of a political philosophy which still dominates parts of the world today – namely the unity of church and state, the merging of ideological and political authority.

Hagia Sophia was constructed as a powerful symbol of that political concept and the more unified form of government it's builder, the late Roman (early Byzantine) emperor, Justinian, imposed.

Justinian, one of the greatest of Roman emperors, built Hagia Sophia and imposed his more centralized political system just two generations after the western European part of the Roman Empire had collapsed, leaving just south-eastern Europe and parts of the Middle East under imperial control.

As a result, Justinian's newly invigorated governmental system shaped aspects of subsequent East European history in ways that did not occur in Western Europe, where church and state became much more separate and politics consequently evolved in more pluralistic and less centralised ways.

The new discoveries at Hagia Sophia show that Justinian's great cathedral was part of a much larger complex of buildings at the heart of the late Roman (Byzantine) imperial capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul) - often dubbed 'the second Rome'. Prior to the investigation, apart from the cathedral itself, there was physical evidence for just two major structures on the site. However, archaeological survey work has revealed that there were at least five, including Hagia Sophia itself.

The newly re-discovered buildings include:

- The great palace that Justinian built for the most senior official of his empire's church, the Patriarch of Constantinople.

- The Great Baptistery – the sumptuous building where Justinian's successors had their children (often future emperors) baptised.

- The Patriarchal Council Chamber – where some of Christianity's most important theological and other decisions were taken (including the historically very significant decision to increase the religious status of the Virgin Mary). The same building also housed the great library of the patriarchs.

The archaeologists also discovered nine 6th century frescoes, two mosaics - and the previously unknown great north-western entrance complex of the cathedral.

The long and detailed investigation has, for the first time in more than five centuries, revealed physical evidence of how Hagia Sophia was part of a larger complex of high status religious buildings at the heart of the Byzantine imperial system. Indeed, Justinian's great cathedral was constructed as the physical representation of the religious and political ideology of his empire.

The archaeological survey has also, for the first time, established how secular imperial power was actually integrated into Hagia Sophia's spiritual rituals. In a seldom-visited part of the cathedral, the archaeologists discovered a 59cm diameter purple marble disc where the Emperor Justinian and his successors used to stand at key moments in religious services.

It's now thought that there was a whole series of such imperial purple discs (each made from purple marble imported from an Imperially-owned quarry in Egypt) at key locations across the cathedral. They seem to have marked the route taken by successive emperors as the Patriarch recited the liturgy a bit like imperial equivalents of the Stations of the Cross.

The investigation also discovered, for the first time, that Justinian had clad his great cathedral in glistening white marble – so that it would shine and shimmer in the rays of the sun. In both Roman and Greek traditions, white symbolised purity.

The new discoveries show how Hagia Sophia was constructed to quite literally shine over the imperial capital. As Justinian, established his new political system, unifying church and state, he seems to have been determined to embed the church at the heart of Roman/Byzantine imperial state identity in a way that never occurred politically in the West.

The new discoveries show how Hagia Sophia was constructed to quite literally shine over the imperial capital. As Justinian, established his new political system, unifying church and state, he seems to have been determined to embed the church at the heart of Roman/Byzantine imperial state identity in a way that never occurred politically in the West.

Other research have discovered how the Romans had built a huge network of tunnels and chambers underneath the cathedral. The Romans had built a huge network of tunnels and chambers underneath the cathedral. It is now estimated that there are more than a thousand metres of tunnels and hidden rooms under Hagia Sophia although most of them have not yet been explored. Archaeologists believe that some were used as water storage cisterns, while others may have functioned as underground chapels and burial areas. Water would have been crucial to the functioning of Justinian's great cathedral complex – partly because of the need to irrigate probable ornate gardens and sustain its once spectacular fountains.

In Roman Constantinople, there was intense and often very violent rivalry between the supporters of the two main teams of charioteers – civil discord that makes modern football rivalries look mild in comparison. What's more, the two charioteer team fan bases had different political identities and aspirations. One was relatively pro-establishment, while the other one was much less so.

Around five years after Justinian came to the imperial throne in AD 527, that rivalry ultimately generated an attempted revolution in which much of central Constantinople (including the city's cathedral) was burnt to the ground and a new anti-Justinian emperor was proclaimed and crowned by the rioters.

After initially preparing to flee the capital, Justinian (encouraged by his very remarkable wife, Theodora), decided to ruthlessly suppress the revolt. Some 30,000 rioters and others were slaughtered and Justinian decided to establish a much more autocratic form of government, unite church and state and create a brand new mega-cathedral, built on new revolutionary architectural principles.

The new Hagia Sophia (literally, 'Divine Wisdom') was in several ways unlike any other building ever constructed in the ancient world.

First of all, it enclosed an unprecedented amount of space some 175,000 cubic metres.

Secondly, it had and still has a vast roughly square floor covering some 5200 square metres of open space.

Now, for the first time, the archaeological investigations have allowed scholars to understand just what Justinian's great cathedral looked like and precisely how massive and politically important it's complex was.

The Independent newspaper, in a January 2021 article, reported on recent archeological research that revealed the original design and subterranean mysteries of Europe's largest ancient landmark the former cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, which for almost a thousand years was the largest conventional building in the world.

The research has, for the first time, revealed the layout of the original sixth century cathedral complex and the existence of more than a kilometre of long-lost tunnels and subterranean chambers underneath the vast building.

The new discoveries are particularly important because, from a political and religious history perspective as well as an architectural one, Hagia Sophia is one of the most significant buildings in the world.

It was originally built to symbolise the establishment of a political philosophy which still dominates parts of the world today – namely the unity of church and state, the merging of ideological and political authority.

Hagia Sophia was constructed as a powerful symbol of that political concept and the more unified form of government it's builder, the late Roman (early Byzantine) emperor, Justinian, imposed.

Justinian, one of the greatest of Roman emperors, built Hagia Sophia and imposed his more centralized political system just two generations after the western European part of the Roman Empire had collapsed, leaving just south-eastern Europe and parts of the Middle East under imperial control.

As a result, Justinian's newly invigorated governmental system shaped aspects of subsequent East European history in ways that did not occur in Western Europe, where church and state became much more separate and politics consequently evolved in more pluralistic and less centralised ways.

The new discoveries at Hagia Sophia show that Justinian's great cathedral was part of a much larger complex of buildings at the heart of the late Roman (Byzantine) imperial capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul) - often dubbed 'the second Rome'. Prior to the investigation, apart from the cathedral itself, there was physical evidence for just two major structures on the site. However, archaeological survey work has revealed that there were at least five, including Hagia Sophia itself.

The newly re-discovered buildings include:

- The great palace that Justinian built for the most senior official of his empire's church, the Patriarch of Constantinople.

- The Great Baptistery – the sumptuous building where Justinian's successors had their children (often future emperors) baptised.

- The Patriarchal Council Chamber – where some of Christianity's most important theological and other decisions were taken (including the historically very significant decision to increase the religious status of the Virgin Mary). The same building also housed the great library of the patriarchs.

The archaeologists also discovered nine 6th century frescoes, two mosaics - and the previously unknown great north-western entrance complex of the cathedral.

The long and detailed investigation has, for the first time in more than five centuries, revealed physical evidence of how Hagia Sophia was part of a larger complex of high status religious buildings at the heart of the Byzantine imperial system. Indeed, Justinian's great cathedral was constructed as the physical representation of the religious and political ideology of his empire.

The archaeological survey has also, for the first time, established how secular imperial power was actually integrated into Hagia Sophia's spiritual rituals. In a seldom-visited part of the cathedral, the archaeologists discovered a 59cm diameter purple marble disc where the Emperor Justinian and his successors used to stand at key moments in religious services.

It's now thought that there was a whole series of such imperial purple discs (each made from purple marble imported from an Imperially-owned quarry in Egypt) at key locations across the cathedral. They seem to have marked the route taken by successive emperors as the Patriarch recited the liturgy a bit like imperial equivalents of the Stations of the Cross.

The investigation also discovered, for the first time, that Justinian had clad his great cathedral in glistening white marble – so that it would shine and shimmer in the rays of the sun. In both Roman and Greek traditions, white symbolised purity.

The new discoveries show how Hagia Sophia was constructed to quite literally shine over the imperial capital. As Justinian, established his new political system, unifying church and state, he seems to have been determined to embed the church at the heart of Roman/Byzantine imperial state identity in a way that never occurred politically in the West.

The new discoveries show how Hagia Sophia was constructed to quite literally shine over the imperial capital. As Justinian, established his new political system, unifying church and state, he seems to have been determined to embed the church at the heart of Roman/Byzantine imperial state identity in a way that never occurred politically in the West.

Other research have discovered how the Romans had built a huge network of tunnels and chambers underneath the cathedral. The Romans had built a huge network of tunnels and chambers underneath the cathedral. It is now estimated that there are more than a thousand metres of tunnels and hidden rooms under Hagia Sophia although most of them have not yet been explored. Archaeologists believe that some were used as water storage cisterns, while others may have functioned as underground chapels and burial areas. Water would have been crucial to the functioning of Justinian's great cathedral complex – partly because of the need to irrigate probable ornate gardens and sustain its once spectacular fountains.

In Roman Constantinople, there was intense and often very violent rivalry between the supporters of the two main teams of charioteers – civil discord that makes modern football rivalries look mild in comparison. What's more, the two charioteer team fan bases had different political identities and aspirations. One was relatively pro-establishment, while the other one was much less so.

Around five years after Justinian came to the imperial throne in AD 527, that rivalry ultimately generated an attempted revolution in which much of central Constantinople (including the city's cathedral) was burnt to the ground and a new anti-Justinian emperor was proclaimed and crowned by the rioters.

After initially preparing to flee the capital, Justinian (encouraged by his very remarkable wife, Theodora), decided to ruthlessly suppress the revolt. Some 30,000 rioters and others were slaughtered and Justinian decided to establish a much more autocratic form of government, unite church and state and create a brand new mega-cathedral, built on new revolutionary architectural principles.

The new Hagia Sophia (literally, 'Divine Wisdom') was in several ways unlike any other building ever constructed in the ancient world.

First of all, it enclosed an unprecedented amount of space some 175,000 cubic metres.

Secondly, it had and still has a vast roughly square floor covering some 5200 square metres of open space.

Now, for the first time, the archaeological investigations have allowed scholars to understand just what Justinian's great cathedral looked like and precisely how massive and politically important it's complex was.

Eastern Turkey - Land of Battles

Eastern Turkey - Land of Battles

From Ankara Scene, Vol. XV, November 11, 1988, Ankara, Turkey

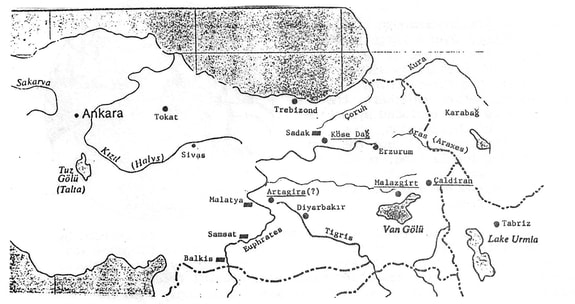

Eastern Turkey appeals because it is so different, even to the visitor coming from Ankara and Western Turkey. Cut off by mountains from the central Anatolian plateau, it lies open instead to Mesopotamia and Asia, and its great rivers-have served as pathways for invaders, its mountains in turn as places of refuge. In the past, as still today, on the border of major powers, it has been the site of great battles, and even one minor engagement, whose outcome has directly affected large parts of the western world.

Conquering and ruling this rugged land have always been two different matters, and although many empires have claimed it, none ever succeeded in bringing it totally under control. Achaemenid, Hellenistic, and Parthian kings, Roman emperors, even Ottoman sultans, were forced to govern not directly but through local rulers who owed, but aid not always give, fealty to the central authority.

Eastern Anatolia may seem especially different to the Western visitor because it lay outside the borders of the Graeco-Roman world, culturally as well as geographically. During most of the Classical period the local rulers owed their allegiance first to the Achaemenids, then to the Parthians, of Iran, who gave them members of the royal family as consorts as well as considerable autonomy. Their ultimate loyalties therefore lay with Parthia, even though they might at times pay homage to Rome during her centuries-long struggle for power in the East.

Attempts to make eastern Anatolia a province of the Roman Empire were thus doomed to failure, as Augustus learned to his great cost. Anxious to ensure that his own descendants would inherit his newly-established empire, Augustus formally adopted his grandson, Gaius Caesar, and made him his heir. When not yet twenty, Gaius was sent on an imperial grand tour of the eastern provinces, to prepare both himself and the East for his eventual rule.

The young man had progressed as far as Syria, everywhere receiving the adulation of loyal provinces, when the throne of Armenia fell vacant. Augustus immediately grasped this opportunity to influence the succession while adding to the prestige of his heir. He directly involved Gaius in the process of choosing a new monarch, then sent him to personally crown the prince deemed most loyal to Rome.

Gaius crossed the Euphrates, to be greeted not by loyal vassals but by civil war. Seeing that Rome's candidate would be king only by force of arms, he and the few troops at his command took part in the siege of a rebel stronghold, the small fortress of Artagira. Lured to a conference by the defenders and treacherously stabbed, Gaius managed to reach the coast and take ship for Rome. But "sick in mind as well as body," he broke his journey in Lycia and on February 21, AD 4, died in the city of Limyra, where German excavators have found and are now restoring his cenotaph.

Augustus's dream of an imperial dynasty died along with Gaius. "Bereaved by Fortune," as he states in the Res Gestae, engraved on the walls of his temple in Ankara, he had no choice but to name his hated stepson Tiberius as his successor. And while Rome continued its efforts to annex eastern Anatolia for another sixty years, it finally accepted that only "by consenting to recognize a Parthian prince as king of Armenia was it possible to maintain a Roman vassal on the throne."

Aside from a few attempts to extend the Empire to the Tigris, during the Pax Romana of the first and second centuries the border between Rome and Parthia ran from Trabzon to the upper Euphrates near Erzurum, then followed the west bank of the river into Syria. This border was guarded by imperial legions stationed at Satala (Sadak), Melitene (Malatya), Samosata (Samsat), and Zeugma (Balkis), with smaller forts in between.

From Ankara Scene, Vol. XV, November 11, 1988, Ankara, Turkey

Eastern Turkey appeals because it is so different, even to the visitor coming from Ankara and Western Turkey. Cut off by mountains from the central Anatolian plateau, it lies open instead to Mesopotamia and Asia, and its great rivers-have served as pathways for invaders, its mountains in turn as places of refuge. In the past, as still today, on the border of major powers, it has been the site of great battles, and even one minor engagement, whose outcome has directly affected large parts of the western world.

Conquering and ruling this rugged land have always been two different matters, and although many empires have claimed it, none ever succeeded in bringing it totally under control. Achaemenid, Hellenistic, and Parthian kings, Roman emperors, even Ottoman sultans, were forced to govern not directly but through local rulers who owed, but aid not always give, fealty to the central authority.

Eastern Anatolia may seem especially different to the Western visitor because it lay outside the borders of the Graeco-Roman world, culturally as well as geographically. During most of the Classical period the local rulers owed their allegiance first to the Achaemenids, then to the Parthians, of Iran, who gave them members of the royal family as consorts as well as considerable autonomy. Their ultimate loyalties therefore lay with Parthia, even though they might at times pay homage to Rome during her centuries-long struggle for power in the East.

Attempts to make eastern Anatolia a province of the Roman Empire were thus doomed to failure, as Augustus learned to his great cost. Anxious to ensure that his own descendants would inherit his newly-established empire, Augustus formally adopted his grandson, Gaius Caesar, and made him his heir. When not yet twenty, Gaius was sent on an imperial grand tour of the eastern provinces, to prepare both himself and the East for his eventual rule.

The young man had progressed as far as Syria, everywhere receiving the adulation of loyal provinces, when the throne of Armenia fell vacant. Augustus immediately grasped this opportunity to influence the succession while adding to the prestige of his heir. He directly involved Gaius in the process of choosing a new monarch, then sent him to personally crown the prince deemed most loyal to Rome.

Gaius crossed the Euphrates, to be greeted not by loyal vassals but by civil war. Seeing that Rome's candidate would be king only by force of arms, he and the few troops at his command took part in the siege of a rebel stronghold, the small fortress of Artagira. Lured to a conference by the defenders and treacherously stabbed, Gaius managed to reach the coast and take ship for Rome. But "sick in mind as well as body," he broke his journey in Lycia and on February 21, AD 4, died in the city of Limyra, where German excavators have found and are now restoring his cenotaph.

Augustus's dream of an imperial dynasty died along with Gaius. "Bereaved by Fortune," as he states in the Res Gestae, engraved on the walls of his temple in Ankara, he had no choice but to name his hated stepson Tiberius as his successor. And while Rome continued its efforts to annex eastern Anatolia for another sixty years, it finally accepted that only "by consenting to recognize a Parthian prince as king of Armenia was it possible to maintain a Roman vassal on the throne."

Aside from a few attempts to extend the Empire to the Tigris, during the Pax Romana of the first and second centuries the border between Rome and Parthia ran from Trabzon to the upper Euphrates near Erzurum, then followed the west bank of the river into Syria. This border was guarded by imperial legions stationed at Satala (Sadak), Melitene (Malatya), Samosata (Samsat), and Zeugma (Balkis), with smaller forts in between.

In Late Roman times, when the Sassanian dynasty had replaced the Parthian and was constantly on the attack, the system of defenses began to change from this set, fortified line to high, impregnable castles which could hold out even if the enemy passed through on raids.

The Byzantines managed to extend the border past the Euphrates, sharing eastern Anatolia with the Persians, but all was lost to the Arabs in the 8th century as they advanced north into the Caucasus and beyond. When Arab power weakened, the local rulers, many now Christian, claimed virtual independence, but in the 11th century a revitalized Byzantium expanded eastward again.

This time the rule was to be very short-lived. Turkmen nomads and Seljuk Turks began annual raids, following the classic invasion route westward along the Araxes (Aras) and upper Euphrates, then spreading out along tributary streams. But the Turkmen were interested only in grazing land, and the Seljuk Turks, it seems, even after taking the cities of Ani and Kars, had no intention of establishing permanent rule. Yet their periodic incursions, the classic confrontation between nomadic herders and settled peasantry and city dwellers, caused total disruption of the eastern provinces.

In response, the Byzantine emperor Romanus Diogenes raised a huge army, estimated at 100,000 men, and marched east from Constantinople. But many of his troops were foreign mercenaries--Frankish and Norman cavalry under their own commander, Roussel, and Cuman Turks from southern Russia--while his second in command, Andronicus Ducas, was a bitter enemy whom he did not dare leave behind.

The Empeoro had reached Manzikert (Turkish Malazgirt) when he received word that the Seljuks under Alp Arslan were coming north from Syria. Even thus forewarned, AlP Arslan took him by surprise in the plain of Manzikert on Friday, August 19, 1071. As Runcirnan descrites it, "The Cumans, remembering that they were Turks and in arrears with their pay, had gone over in a body on the previous night to join the enemy; and Roussel and his Franks decided to take no part in the battle. Andronicus Ducas … drew the reserve troops under his command away from the battlefield and marched them westward, leaving the Emperor to his fate. ...By evening the Byzantine army was destroyed and Romanus wounded and a prisoner. "

Although Alp Arslan demanded little more from his victory than a large ransom for the emperor, "that dreadful day," as later Byzantine historians always described it, had far-reaching consequences. After Manzikert, the West could claim to have replaced Byzantium as protector of Christendom, thus justifying the Crusades. But the most important, and long-lasting, result of Alp's victory was that Anatolia would change from Byzantine and Christian to Turkish and Moslem.

As Runciman notes, the Byzantines made this change even more certain by their immediate actions. Set free by Alp Arslan, Romanus Diogenes was deposed at Constantinople, his eyes put out "so savagely that he died a few days later." In the resulting civil war, Roussel tried to establish a Frankish state in western Anatolia and was stopped only when the Byzantine emperor called in the Seljuks, who alone had an army strong enough to defeat him. Within a few years the Seljuks, almost despite themselves, had formed the Sultanate of Rum in what had been "Roman" (i.e., Byzantine) Anatolia.

Today, the main monuments of this Seljuk state are the stone caravansaries which do the countryside of central Anatolia. Almost all have elaborately carved entrance portals, refectling the influence of various cultures. An additional charm, at least to the pedant, is that they are easy to date, because Seljuk rule was brief, cut of in its prime by the Mongols.

Preceded by their dreadful reputation for invincibility in battle and delight in mindless slaughter, the Mongols took Erzurum in the winter of 1243-4, and used it as a base of attack the following spring. The Seljuk Sultan Kaykhusraw II called upon not only his vassals, allies, and Frankish mercenaries but also former enemies such as the Armenians to muster at Sivas against the common enemy.

"Around him, " says Cahen, "people alternated between the usual panic whenever the Mongols approached, and impatience to go out to halt them, rather than wait until they had occupied or devastated half the realm." Kaykhusraw marched east without waiting for those troops who were delayed (some deliberately), and took up a position at the pass of Kose Dag. The Mongol army, although trapped, relied once again on its famous ruse, pretending to flee in panic and defeat, then suddenly wheeling upon an enemy strung out in pursuit and careless in presumed victory. By the evening of June 26, 1243, the Seljuk army had been totally destroyed. The Sultan fled all the way to Ankara, stopping only to pick up his treasure which had been left for safety in Tokat. "In one day, the course of the history of Asia Minor had been changed beyond recall."

Rarely has one battle been so decisive. Because of Kose Dag, the Turkish dynasty which was to rule Anatolia and well beyond for 500 years was not Seljuk but Ottoman. After taking Constantinople in 1453 the Ottoman Turks, now themselves the established rulers of an empire, tried in their turn to bring eastern Anatolia and its nomadic tribes under direct control. The nomads, however, were no more anxious to submit to the Ottomans than to any other central authority. Their resistance made them ready converts to the Safavid movement, a militant Shi'i heresy and thus anathema to the orthodox Sunnism of the Ottanan state. "Then, as later," explains Shaw, "religion in the Middle East served as a vehicle for the expression of political feelings and ambitions."

The Safavid leader Ismail (1487-1524) was driven into Iran, but within a few years he had eliminated the local dynasts there and gained control of the entire country. From this safe haven the Safavids sent itinerant preachers to the nomads of eastern Anatolia, who became a focus of all discontent. Selim, the grandson of Mehmet the Conqueror, came to know and fear the Safavids while governor of Trabzon, and as soon as he became sultan determined to eliminate them.

As Selim led his army eastward, Ismail retreated, trying to draw the Ottomans into the rugged mountains of northwest Iran. But when Selim made clear his intention of marching directly to the Safavid capital at Tabriz, the two armies met half-way, on August, 23, 1514, in the plain of Caldiran. Casualties were heavy on both sides, but the Ottomans succeeded in turning almost a certain defeat into victory, and Ismail barely managed to escape, wounded and almost alone.

The Ottomans then proceeded to take Tabriz, but because of difficulties in supply Selim withdrew to Karabag in the Caucasus, "the favorite wintering place of the nomadic hordes of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane before him,". But in early winter he was forced to lead his army back to Anatolia, and suffered great losses on the march.

Claimed as an Ottoman victory, Caldiran was more of a standoff. The Safavids accepted that trey could not defeat the Ottoman armies in the plain, although they did not cease their propaganda among the tribes of eastern Anatolia, especially at times of Ottoman weakness. For his part, Selim abandoned his attempt to extirpate the Safavids and instead turned south to add the Arab lands, including the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina, to the empire. And though his son, Suleyman the Magnificent, was to extend the border even further east, adding Van and Kars and Karabag, he too was forced to accept the existence of the Safavids, and with them the division of Islam into two, often warring, sects.

To administer their vast new empire, Selim and his immediate successors replaced the feudal rule of the old Ottoman aristocracy with a centralized government, run by a new bureaucracy and army loyal only to themselves. But in order to retain even nominal control of eastern Anatolia, the Sultans accepted that they must here rule not directly but through the local lords, the famous (and infamously unreliable) feudal agas, some of whom, in title at least, remain to this day.

By Toni M. Cross

ARIT - Ankara Director (1979-2002)

The American Research Institute in Turkey

The Byzantines managed to extend the border past the Euphrates, sharing eastern Anatolia with the Persians, but all was lost to the Arabs in the 8th century as they advanced north into the Caucasus and beyond. When Arab power weakened, the local rulers, many now Christian, claimed virtual independence, but in the 11th century a revitalized Byzantium expanded eastward again.

This time the rule was to be very short-lived. Turkmen nomads and Seljuk Turks began annual raids, following the classic invasion route westward along the Araxes (Aras) and upper Euphrates, then spreading out along tributary streams. But the Turkmen were interested only in grazing land, and the Seljuk Turks, it seems, even after taking the cities of Ani and Kars, had no intention of establishing permanent rule. Yet their periodic incursions, the classic confrontation between nomadic herders and settled peasantry and city dwellers, caused total disruption of the eastern provinces.

In response, the Byzantine emperor Romanus Diogenes raised a huge army, estimated at 100,000 men, and marched east from Constantinople. But many of his troops were foreign mercenaries--Frankish and Norman cavalry under their own commander, Roussel, and Cuman Turks from southern Russia--while his second in command, Andronicus Ducas, was a bitter enemy whom he did not dare leave behind.

The Empeoro had reached Manzikert (Turkish Malazgirt) when he received word that the Seljuks under Alp Arslan were coming north from Syria. Even thus forewarned, AlP Arslan took him by surprise in the plain of Manzikert on Friday, August 19, 1071. As Runcirnan descrites it, "The Cumans, remembering that they were Turks and in arrears with their pay, had gone over in a body on the previous night to join the enemy; and Roussel and his Franks decided to take no part in the battle. Andronicus Ducas … drew the reserve troops under his command away from the battlefield and marched them westward, leaving the Emperor to his fate. ...By evening the Byzantine army was destroyed and Romanus wounded and a prisoner. "

Although Alp Arslan demanded little more from his victory than a large ransom for the emperor, "that dreadful day," as later Byzantine historians always described it, had far-reaching consequences. After Manzikert, the West could claim to have replaced Byzantium as protector of Christendom, thus justifying the Crusades. But the most important, and long-lasting, result of Alp's victory was that Anatolia would change from Byzantine and Christian to Turkish and Moslem.

As Runciman notes, the Byzantines made this change even more certain by their immediate actions. Set free by Alp Arslan, Romanus Diogenes was deposed at Constantinople, his eyes put out "so savagely that he died a few days later." In the resulting civil war, Roussel tried to establish a Frankish state in western Anatolia and was stopped only when the Byzantine emperor called in the Seljuks, who alone had an army strong enough to defeat him. Within a few years the Seljuks, almost despite themselves, had formed the Sultanate of Rum in what had been "Roman" (i.e., Byzantine) Anatolia.

Today, the main monuments of this Seljuk state are the stone caravansaries which do the countryside of central Anatolia. Almost all have elaborately carved entrance portals, refectling the influence of various cultures. An additional charm, at least to the pedant, is that they are easy to date, because Seljuk rule was brief, cut of in its prime by the Mongols.

Preceded by their dreadful reputation for invincibility in battle and delight in mindless slaughter, the Mongols took Erzurum in the winter of 1243-4, and used it as a base of attack the following spring. The Seljuk Sultan Kaykhusraw II called upon not only his vassals, allies, and Frankish mercenaries but also former enemies such as the Armenians to muster at Sivas against the common enemy.

"Around him, " says Cahen, "people alternated between the usual panic whenever the Mongols approached, and impatience to go out to halt them, rather than wait until they had occupied or devastated half the realm." Kaykhusraw marched east without waiting for those troops who were delayed (some deliberately), and took up a position at the pass of Kose Dag. The Mongol army, although trapped, relied once again on its famous ruse, pretending to flee in panic and defeat, then suddenly wheeling upon an enemy strung out in pursuit and careless in presumed victory. By the evening of June 26, 1243, the Seljuk army had been totally destroyed. The Sultan fled all the way to Ankara, stopping only to pick up his treasure which had been left for safety in Tokat. "In one day, the course of the history of Asia Minor had been changed beyond recall."

Rarely has one battle been so decisive. Because of Kose Dag, the Turkish dynasty which was to rule Anatolia and well beyond for 500 years was not Seljuk but Ottoman. After taking Constantinople in 1453 the Ottoman Turks, now themselves the established rulers of an empire, tried in their turn to bring eastern Anatolia and its nomadic tribes under direct control. The nomads, however, were no more anxious to submit to the Ottomans than to any other central authority. Their resistance made them ready converts to the Safavid movement, a militant Shi'i heresy and thus anathema to the orthodox Sunnism of the Ottanan state. "Then, as later," explains Shaw, "religion in the Middle East served as a vehicle for the expression of political feelings and ambitions."

The Safavid leader Ismail (1487-1524) was driven into Iran, but within a few years he had eliminated the local dynasts there and gained control of the entire country. From this safe haven the Safavids sent itinerant preachers to the nomads of eastern Anatolia, who became a focus of all discontent. Selim, the grandson of Mehmet the Conqueror, came to know and fear the Safavids while governor of Trabzon, and as soon as he became sultan determined to eliminate them.

As Selim led his army eastward, Ismail retreated, trying to draw the Ottomans into the rugged mountains of northwest Iran. But when Selim made clear his intention of marching directly to the Safavid capital at Tabriz, the two armies met half-way, on August, 23, 1514, in the plain of Caldiran. Casualties were heavy on both sides, but the Ottomans succeeded in turning almost a certain defeat into victory, and Ismail barely managed to escape, wounded and almost alone.

The Ottomans then proceeded to take Tabriz, but because of difficulties in supply Selim withdrew to Karabag in the Caucasus, "the favorite wintering place of the nomadic hordes of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane before him,". But in early winter he was forced to lead his army back to Anatolia, and suffered great losses on the march.

Claimed as an Ottoman victory, Caldiran was more of a standoff. The Safavids accepted that trey could not defeat the Ottoman armies in the plain, although they did not cease their propaganda among the tribes of eastern Anatolia, especially at times of Ottoman weakness. For his part, Selim abandoned his attempt to extirpate the Safavids and instead turned south to add the Arab lands, including the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina, to the empire. And though his son, Suleyman the Magnificent, was to extend the border even further east, adding Van and Kars and Karabag, he too was forced to accept the existence of the Safavids, and with them the division of Islam into two, often warring, sects.

To administer their vast new empire, Selim and his immediate successors replaced the feudal rule of the old Ottoman aristocracy with a centralized government, run by a new bureaucracy and army loyal only to themselves. But in order to retain even nominal control of eastern Anatolia, the Sultans accepted that they must here rule not directly but through the local lords, the famous (and infamously unreliable) feudal agas, some of whom, in title at least, remain to this day.

By Toni M. Cross

ARIT - Ankara Director (1979-2002)

The American Research Institute in Turkey

LATE ROMAN TETRARCHY

|

Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 286 and 293. The division of the Roman Empire into four parts.

The Tetrarchs, porphyry sculpture, ca. 300 AD, of the four emperors of the first Tetrarchy ("rule of four"instituted by Emperor Diocletian. It show the four rulers (Diocletian, co-augustus Maximian and Galerius and Constantius 1 as their caesars; Constantius was father to Constantine the Great) in a cordial embrace intended as an expression of concordia, or agreement. Originally located in Byzantine Philadelphion palace, Constantinople, the sculpture was plundered during the Crusade of 1204, taken back to Venice and incorporated into the facade of the Treasury of St. Marks, Venice. A shift in orientation of style The sculpture of the Tetrarchs exemplifies and marks the change in approach to representation from a classical to a medieval mentality. |

The tetrarchy (literally "rule of four") led the Roman Empire from 293 to 313. Established by Emperor Diocletian to share the responsibilities of government fro the Empire and to prepare the next leaders for rule, it could not survive the bellicose jealousies of its second generation, with Constantine the surviving emperor. The statue, carved around the time, depicts the unity of the then peaceful four leaders. As they were also military leaders, they are dressed in lorica segmental armour, a bronze breastplate from which bronze strips descend in a skirt of two connected layers to the knees. The shoulders and upper arms are covered with three layers of bronze strips. (Layering aids in the movement of the arms and lower torso). An undergarment to which this armour may be connected can be seen on the arms and slightly below the skirt. Their scabbarded weapons are spats, long swords especially populare among Roman cavalry, although the long hilts may also indicate that they could be grasped by two hands and used fro fighting when the soldier had dismounted.

Currently the statue is outside the Basilica of San Marco, brought there from Constantinople by the Venetian Fourth Crusaders after the sack of the city in 1204.

Reference:

DeVries, Kelly andSmith, Robert D. Medieval Weapons - An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO Press, Santa Barbara, CA.. page 169 and 219.

Currently the statue is outside the Basilica of San Marco, brought there from Constantinople by the Venetian Fourth Crusaders after the sack of the city in 1204.

Reference:

DeVries, Kelly andSmith, Robert D. Medieval Weapons - An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO Press, Santa Barbara, CA.. page 169 and 219.

Understanding Byzantine Economy: The Collapse of a Medieval Powerhouse

Understanding Byzantine Economy: The Collapse of a Medieval Powerhouse

As the successors of the Romans, the Byzantines maintained one of the most advanced economies in medieval times. However, this great wealth dramatically collapsed in the 13th century.

From the first partition of the Roman Empire in 284, the Eastern or ‘Byzantine’ Empire as it came to be known, was an economic powerhouse. With an advanced state tax system and trade links reaching across Eurasia, the Byzantine economy maintained an important position into medieval times, projecting an image of great wealth and prestige. However, the 1204 Fourth Crusade proved to be a catastrophe, plunging Byzantium into an economic decline from which it never recovered. Upon the eve of the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the once-great Byzantine Empire was effectively destitute, a pitiable shell of its former glory.

The power of the Byzantine Empire’s early economy was largely predicated upon the land. Anatolia, the Levant, and Egypt were well developed agricultural regions which yielded huge amounts of tax revenues for the state – some estimate that Egypt alone may have contributed up to 30% of the annual tax take.

The climate across the empire was excellent for various types of farming activity. In coastal areas cereal crops, vines and olives were produced in vast quantities, whereas interior areas were mainly given over to raising livestock of various kinds. Fruits and vegetables were also widely produced, including in urban centers – there were large sections of Constantinople given over to gardening.

Agricultural production was based around the village. Villages were occupied by a variety of inhabitants, many of them landholding farmers who owned their land and therefore paid taxes directly to the state. Gradually, this system was replaced by a network of large estates worked by a mixture of slaves, wage laborers and tenant farmers.

From the 10th century, the concentration of land in the hands of fewer and fewer powerful noble families accelerated, and successive emperors passed a series of ‘land laws’ attempting to prevent the alienation of land from small landholding farmers. Despite this legislation, by the high middle ages, the rural landscape of Byzantium had changed completely – the patchwork of small villages that had previously made up the agricultural economy had been almost entirely replaced by large estates.

These powerful landowning families (particularly concentrated in Anatolia) represented a political threat to the imperial crown in Constantinople, as they were essentially self-sufficient, with their own tenants and retinues. For example, Bardas Skleros, Byzantine general and member of the Skleroi family who held vast estates in the east led a revolt against Basil II that lasted from 976-79.

As the successors of the Romans, the Byzantines maintained one of the most advanced economies in medieval times. However, this great wealth dramatically collapsed in the 13th century.

From the first partition of the Roman Empire in 284, the Eastern or ‘Byzantine’ Empire as it came to be known, was an economic powerhouse. With an advanced state tax system and trade links reaching across Eurasia, the Byzantine economy maintained an important position into medieval times, projecting an image of great wealth and prestige. However, the 1204 Fourth Crusade proved to be a catastrophe, plunging Byzantium into an economic decline from which it never recovered. Upon the eve of the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the once-great Byzantine Empire was effectively destitute, a pitiable shell of its former glory.

The power of the Byzantine Empire’s early economy was largely predicated upon the land. Anatolia, the Levant, and Egypt were well developed agricultural regions which yielded huge amounts of tax revenues for the state – some estimate that Egypt alone may have contributed up to 30% of the annual tax take.

The climate across the empire was excellent for various types of farming activity. In coastal areas cereal crops, vines and olives were produced in vast quantities, whereas interior areas were mainly given over to raising livestock of various kinds. Fruits and vegetables were also widely produced, including in urban centers – there were large sections of Constantinople given over to gardening.

Agricultural production was based around the village. Villages were occupied by a variety of inhabitants, many of them landholding farmers who owned their land and therefore paid taxes directly to the state. Gradually, this system was replaced by a network of large estates worked by a mixture of slaves, wage laborers and tenant farmers.

From the 10th century, the concentration of land in the hands of fewer and fewer powerful noble families accelerated, and successive emperors passed a series of ‘land laws’ attempting to prevent the alienation of land from small landholding farmers. Despite this legislation, by the high middle ages, the rural landscape of Byzantium had changed completely – the patchwork of small villages that had previously made up the agricultural economy had been almost entirely replaced by large estates.

These powerful landowning families (particularly concentrated in Anatolia) represented a political threat to the imperial crown in Constantinople, as they were essentially self-sufficient, with their own tenants and retinues. For example, Bardas Skleros, Byzantine general and member of the Skleroi family who held vast estates in the east led a revolt against Basil II that lasted from 976-79.

|

Taxation in The Byzantine Empire

Thanks to its Roman history, Byzantium possessed an advanced bureaucracy and tax collection system that had been introduced by the emperor Diocletian (284-305 AD), based around capita(‘heads’) and iugera (‘land’). Constantine (306-37 AD), emperor and founder of Constantinople, had sought to combat inflation by minting a large amount of high-quality, high-carat gold pieces. It was this currency, known as Nomisma or Solidus that formed the monetary basis of the Byzantine economy, and stayed fairly stable until the 11th century. Later emperors instituted further fiscal reforms, and the period up until 7th-century was a time of considerable growth. Anastasius I (491-518) introduced a bronze coinage and abolished the chrysargyron, an imperial tax on merchants. He also removed tax-collecting powers from the hands of local dignitaries and instead gave them to state-appointed officials, whilst also formalizing military payrolls, thereby reducing corruption and increasing the state treasury. This great wealth allowed subsequent emperors such as Justinian I (527-65) to expand the empire through conquest. The most important of Byzantine taxes was the land tax, which was calculated based on the value of the land that each person owned. The division used was a modius (roughly equivalent to ¼ of an acre): high-quality land was valued at 1 gold coin, second-rate land was worth ½ a gold coin, and pasture 1/3, while vineyards were valued much higher than other lands. Peasants also paid a personal tax which later on became a household tax, known as the kapnikos. |

Trade

Aside from agriculture, trade was an important element of the Byzantine economy. Constantinople was positioned along both the east-west and north-south trade routes, and the Byzantines took advantage of this by taxing imports and exports at a 10% rate. Grain was a key import, particularly after the Arab conquests of Egypt and the Levant meant the empire lost its primary sources of grain.

Silk was also an important Byzantine import, as it was crucial to the state for diplomatic and prestigious purposes. However, after silkworms were smuggled into the empire from China, the Byzantines developed their own silk industry and no longer had to rely on foreign supplies.

Various other commodities were also traded, both internally within the empire, and internationally beyond its borders. Oil, wine, salt, fish, meat and other foods were all traded, as were materials such as timber and wax. Manufactured items such as ceramics, linens and cloth were also exchanged, as well as luxuries such as spices, silks and perfumes.

Trade was also important to Byzantine diplomacy – through maintaining trade relations, the Byzantines could bring various peoples and nations into their sphere of influence and potentially use them in regional alliances. Bulgarian and Russian merchants brought wax, honey, furs and linen, while hides and wax were purchased from the Pechenegs, a nomadic people who lived north of the Black Sea in the 10th century. Spices and manufactured goods entered the empire from the east, usually in trade caravans that passed through the cities of Anatolia. Venice was also a trading partner, and by 992 Venetian naval power was considerable enough to warrant Venetian merchants being granted a reduction in customs duties in Constantinople.

Aside from agriculture, trade was an important element of the Byzantine economy. Constantinople was positioned along both the east-west and north-south trade routes, and the Byzantines took advantage of this by taxing imports and exports at a 10% rate. Grain was a key import, particularly after the Arab conquests of Egypt and the Levant meant the empire lost its primary sources of grain.

Silk was also an important Byzantine import, as it was crucial to the state for diplomatic and prestigious purposes. However, after silkworms were smuggled into the empire from China, the Byzantines developed their own silk industry and no longer had to rely on foreign supplies.

Various other commodities were also traded, both internally within the empire, and internationally beyond its borders. Oil, wine, salt, fish, meat and other foods were all traded, as were materials such as timber and wax. Manufactured items such as ceramics, linens and cloth were also exchanged, as well as luxuries such as spices, silks and perfumes.

Trade was also important to Byzantine diplomacy – through maintaining trade relations, the Byzantines could bring various peoples and nations into their sphere of influence and potentially use them in regional alliances. Bulgarian and Russian merchants brought wax, honey, furs and linen, while hides and wax were purchased from the Pechenegs, a nomadic people who lived north of the Black Sea in the 10th century. Spices and manufactured goods entered the empire from the east, usually in trade caravans that passed through the cities of Anatolia. Venice was also a trading partner, and by 992 Venetian naval power was considerable enough to warrant Venetian merchants being granted a reduction in customs duties in Constantinople.

Bureaucracy and Organization

The state held a monopoly on coinage and intervened in the economy in various ways. It controlled interest rates and carefully orchestrated economic activity in Constantinople, setting stringent regulations for the city’s guilds to follow (which can be seen in the 10th-century text, the Book of the Eparch). The state also intervened to ensure that the capital was provisioned with grain and to drive down the cost of bread – riots could occur that threatened the emperor’s reign if food was not cheap and readily available in Constantinople.

Despite the upheaval of the early medieval period, the Byzantine Empire still maintained a wide-reaching bureaucracy and powerful state mechanisms, which allowed it to have standing armies and effective tax collection. As it was so large, the state also created a huge amount of economic demand, meaning market forces had little effect on the Byzantine economy. Soldiers and bureaucrats were paid in gold coin, which they used to purchase goods, ensuring coinage was effectively recycled through the economy and ended up back in the hands of the state through taxation of the peasantry and rural elite.

The state held a monopoly on coinage and intervened in the economy in various ways. It controlled interest rates and carefully orchestrated economic activity in Constantinople, setting stringent regulations for the city’s guilds to follow (which can be seen in the 10th-century text, the Book of the Eparch). The state also intervened to ensure that the capital was provisioned with grain and to drive down the cost of bread – riots could occur that threatened the emperor’s reign if food was not cheap and readily available in Constantinople.

Despite the upheaval of the early medieval period, the Byzantine Empire still maintained a wide-reaching bureaucracy and powerful state mechanisms, which allowed it to have standing armies and effective tax collection. As it was so large, the state also created a huge amount of economic demand, meaning market forces had little effect on the Byzantine economy. Soldiers and bureaucrats were paid in gold coin, which they used to purchase goods, ensuring coinage was effectively recycled through the economy and ended up back in the hands of the state through taxation of the peasantry and rural elite.

The Early Byzantine Economy To 7th Century Crisis

The Eastern Roman Empire suffered far less than the Western half of the empire during the 4th and 5th centuries when the Western Empire was subjected to repeated barbarian raids and eventually collapsed altogether in 476. Figures actually suggest that urban centers in the east grew, and the imperial revenues remained consistently high, allowing Justinian I to embark upon wars of expansion, as well as imperial building projects such as the great cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

The 6th and 7th centuries were disastrous for the Byzantine economy. The great plague of 541/2 ravaged the empire and may have reduced the population by up to 30%. Subsequent recurrences of the pestilence were common and lasted well into the 8th century. A costly war with Persia also drained the state coffers during the 6th century. Annual revenue, which stood at around 11 million solidi in 540 dropped to just 6 million in 555.

Furthermore, the empire lost a great deal of land to foreign conquest: Arab invaders captured the Levant, Egypt and North Africa as part of the first Muslim conquests; the Lombards moved into Italy; the Balkans were taken by Slavic peoples. The losses of the eastern provinces were the greatest blow, as they may have accounted for as much as 75% of the Byzantine economy. Population loss was also enormous – over a 40-year period, the population of the empire may have shrunk by as much as 6.5 million, from 17 million in 600 to 10.5 million in 641. Revenues also dropped drastically to just 2 million nomismata in 668.

The Eastern Roman Empire suffered far less than the Western half of the empire during the 4th and 5th centuries when the Western Empire was subjected to repeated barbarian raids and eventually collapsed altogether in 476. Figures actually suggest that urban centers in the east grew, and the imperial revenues remained consistently high, allowing Justinian I to embark upon wars of expansion, as well as imperial building projects such as the great cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

The 6th and 7th centuries were disastrous for the Byzantine economy. The great plague of 541/2 ravaged the empire and may have reduced the population by up to 30%. Subsequent recurrences of the pestilence were common and lasted well into the 8th century. A costly war with Persia also drained the state coffers during the 6th century. Annual revenue, which stood at around 11 million solidi in 540 dropped to just 6 million in 555.

Furthermore, the empire lost a great deal of land to foreign conquest: Arab invaders captured the Levant, Egypt and North Africa as part of the first Muslim conquests; the Lombards moved into Italy; the Balkans were taken by Slavic peoples. The losses of the eastern provinces were the greatest blow, as they may have accounted for as much as 75% of the Byzantine economy. Population loss was also enormous – over a 40-year period, the population of the empire may have shrunk by as much as 6.5 million, from 17 million in 600 to 10.5 million in 641. Revenues also dropped drastically to just 2 million nomismata in 668.

Renewal: Byzantium As A Medieval Economic Powerhouse

The failed siege of Constantinople by the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate in 717-18 marked something of a turning point for Byzantine fortunes, and emperors such as Constantine V (741-75) were able to secure the borders of Byzantium and pave the way for an economic recovery.

Although international commerce had declined dramatically during the 7th century, it slowly recovered during the following centuries thanks to increased political and military stability, until in 850 trade accounted for 400,000 of the total 2.9 million nomismata state revenue. Successive emperors were able to accumulate increasingly larger reserves in the state treasury – these totaled 4.3 million nomismata during the reign of Basil I (867-86).

From the 10th until the 12th century, Byzantium enjoyed considerable economic prosperity, with annual revenues in 1025 standing at 5.9 million nomismata, and a treasury reserve of 14.4 million. This wealth allowed the Byzantine empire and its emperors to project an image of their power abroad, increasing their own prestige. Visitors to Constantinople, such as the Italian diplomat Liutprand of Cremona, were impressed by the luxurious imperial palaces and incredible riches that they witnessed in the city. However, this economic success was not to last.

The failed siege of Constantinople by the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate in 717-18 marked something of a turning point for Byzantine fortunes, and emperors such as Constantine V (741-75) were able to secure the borders of Byzantium and pave the way for an economic recovery.

Although international commerce had declined dramatically during the 7th century, it slowly recovered during the following centuries thanks to increased political and military stability, until in 850 trade accounted for 400,000 of the total 2.9 million nomismata state revenue. Successive emperors were able to accumulate increasingly larger reserves in the state treasury – these totaled 4.3 million nomismata during the reign of Basil I (867-86).

From the 10th until the 12th century, Byzantium enjoyed considerable economic prosperity, with annual revenues in 1025 standing at 5.9 million nomismata, and a treasury reserve of 14.4 million. This wealth allowed the Byzantine empire and its emperors to project an image of their power abroad, increasing their own prestige. Visitors to Constantinople, such as the Italian diplomat Liutprand of Cremona, were impressed by the luxurious imperial palaces and incredible riches that they witnessed in the city. However, this economic success was not to last.

13th Century Disasters and the End Of Byzantium

Several factors contributed to the terminal decline of the Byzantine economy, the greatest among which was undoubtedly the fourth crusade. Beginning in 1202, the crusaders had originally intended to attack Jerusalem via Egypt but ended up encountering financial issues that saw them attack the Christian city of Zara on the Adriatic. En route to Jerusalem, they entered into an agreement to aid the Byzantine prince Alexios Angelos in restoring his father Issac II to the Byzantine throne, in return for military and financial aid.

In 1204, when the newly crowned co-emperor Alexios was overthrown by a mob in Constantinople, the crusaders simply decided to conquer the city. What followed was the brutal sack of Constantinople in April 1204. For three days the crusaders looted and vandalized the great city, stealing much of the vast wealth that had been accumulated over many centuries. Ancient Greek and Roman works were taken or else destroyed (the famous bronze horses from the Hippodrome were taken back to Venice and now decorate St. Mark’s Basilica there), and Constantinople’s churches were systematically plundered. The human cost was enormous too, with many thousands of civilians being massacred in cold blood.

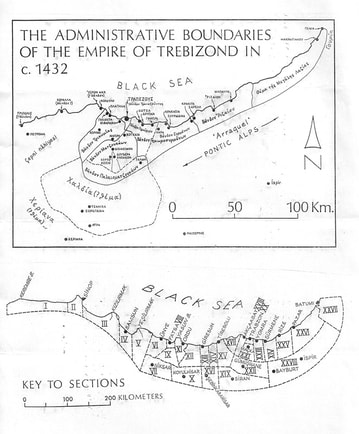

The crusaders left a gutted and destroyed city behind – it is estimated that Constantinople was looted of some 3.6 million hyperpyra (the currency that had replaced the nomismata). The crusader leaders divided the empire amongst themselves into what became known as the Latin Empire, while the Byzantines were left with three successor states: The Empire of Nicea, the Despotate of Epirus, and the Empire of Trebizond. The Nicean Empire lost a great deal of territory in southern Anatolia to the Sultanate of Rum, and by the time it recaptured Constantinople from the Latins in 1261 and reestablished the Byzantine Empire, it was ravaged by warfare.

Subsequent emperors attempted to expand the empire and restore some of its former glory but were hampered by a shattered economy. A reliance on harsh taxation angered the peasantry and the use of mercenary troops proved to be unreliable and ineffective. From the mid-14th century until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the empire slowly lost territory to Serbian andOttoman aggressors. It is estimated that in 1321 the annual state revenue stood at just 1 million hyperpyra.

By the time of the siege in 1453, the once-great Byzantine empire effectively consisted only of territory on the European side of the Bosporus surrounding Constantinople. The city itself was hugely underpopulated and in a state of extreme disrepair – it could only muster 7,000 soldiers to defend itself, 2,000 of whom were foreign (primarily Italians). Constantinople, and the Byzantine Empire with it, fell on 29th May 1453 after a two-month siege. The last Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos was seen throwing himself and his retinue into the fiercest hand-to-hand combat following the fall of the walls.

Several factors contributed to the terminal decline of the Byzantine economy, the greatest among which was undoubtedly the fourth crusade. Beginning in 1202, the crusaders had originally intended to attack Jerusalem via Egypt but ended up encountering financial issues that saw them attack the Christian city of Zara on the Adriatic. En route to Jerusalem, they entered into an agreement to aid the Byzantine prince Alexios Angelos in restoring his father Issac II to the Byzantine throne, in return for military and financial aid.

In 1204, when the newly crowned co-emperor Alexios was overthrown by a mob in Constantinople, the crusaders simply decided to conquer the city. What followed was the brutal sack of Constantinople in April 1204. For three days the crusaders looted and vandalized the great city, stealing much of the vast wealth that had been accumulated over many centuries. Ancient Greek and Roman works were taken or else destroyed (the famous bronze horses from the Hippodrome were taken back to Venice and now decorate St. Mark’s Basilica there), and Constantinople’s churches were systematically plundered. The human cost was enormous too, with many thousands of civilians being massacred in cold blood.

The crusaders left a gutted and destroyed city behind – it is estimated that Constantinople was looted of some 3.6 million hyperpyra (the currency that had replaced the nomismata). The crusader leaders divided the empire amongst themselves into what became known as the Latin Empire, while the Byzantines were left with three successor states: The Empire of Nicea, the Despotate of Epirus, and the Empire of Trebizond. The Nicean Empire lost a great deal of territory in southern Anatolia to the Sultanate of Rum, and by the time it recaptured Constantinople from the Latins in 1261 and reestablished the Byzantine Empire, it was ravaged by warfare.

Subsequent emperors attempted to expand the empire and restore some of its former glory but were hampered by a shattered economy. A reliance on harsh taxation angered the peasantry and the use of mercenary troops proved to be unreliable and ineffective. From the mid-14th century until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the empire slowly lost territory to Serbian andOttoman aggressors. It is estimated that in 1321 the annual state revenue stood at just 1 million hyperpyra.

By the time of the siege in 1453, the once-great Byzantine empire effectively consisted only of territory on the European side of the Bosporus surrounding Constantinople. The city itself was hugely underpopulated and in a state of extreme disrepair – it could only muster 7,000 soldiers to defend itself, 2,000 of whom were foreign (primarily Italians). Constantinople, and the Byzantine Empire with it, fell on 29th May 1453 after a two-month siege. The last Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos was seen throwing himself and his retinue into the fiercest hand-to-hand combat following the fall of the walls.

References

A Study of History - List of Civilizations

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

ATLAS OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE

| atlas_of_medieval_europe.pdf | |

| File Size: | 14705 kb |

| File Type: | |

Byzantium Historical Writing

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Return of the Relics of Sts. Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom

Go to link: www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Eztvp0CN4Q&feature=youtu.be

Go to link: www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Eztvp0CN4Q&feature=youtu.be

Timeline of the Roman and Byzantine Emperors

Go to link: www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Eztvp0CN4Q&feature=youtu.be

Go to link: www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Eztvp0CN4Q&feature=youtu.be

2020 Converstion of the Hagia Sophia Musuem to a Mosque