Christian Art and Iconography in Byzantium

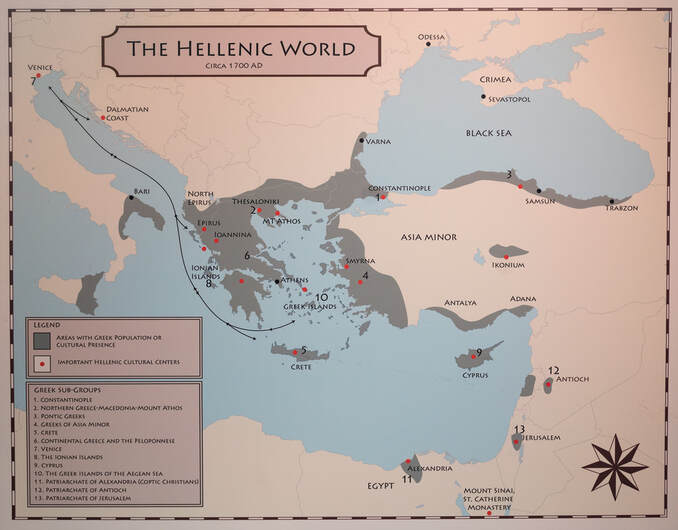

Byzantine and Greek Iconography of the Hellenic World

Greek Influence of the Hellenic World

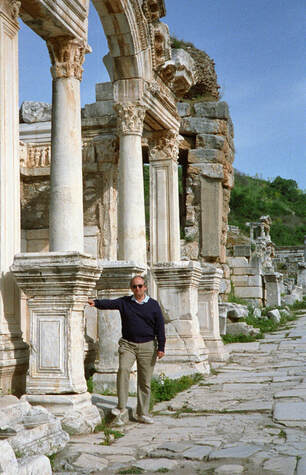

Roman Influence

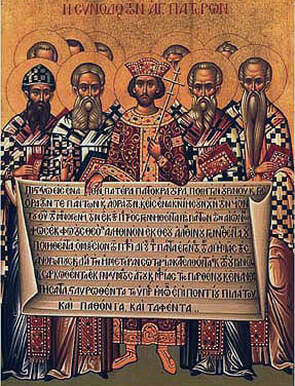

Byzantine Christain Art

Byzantine Art:

D. Talbot Rice, Professor of Fine Arts in the University of Edinburgh c.1935 book on “Byzantine Art”:

The author’s definition of “Byzantine” includes “all the work produced in the Byzantine sphere” (namely, in the Balkans, in Armenia, in Russia, in Italy, Africa, Greece, and in Asia Minor) “…and especially at Constantinople after the synthesis of East and West, of Greek, of Roman, of Syrian, and of Persian elements had been brought about as the outcome of the adoption of Christianity as the state religion”. For more than ten centuries these cultural streams and their many tributaries had flowed through Constantinople east and west and into the Slavonic world. This created a “fruitful traffic in ideas” between the Byzantine capita and the Christian and Moslem worlds. One sees in Byzantine art something “which links it, as far as aims and methods are concerned with the art of today..” We should not the judge Byzantine art by Greco-Roman Renaissance criteria it is this short-sighted approach to Byzantine art which, in the past, led the academic dogmatists to criticize it as a manifestation of decadence.

D. Talbot Rice, Professor of Fine Arts in the University of Edinburgh c.1935 book on “Byzantine Art”:

The author’s definition of “Byzantine” includes “all the work produced in the Byzantine sphere” (namely, in the Balkans, in Armenia, in Russia, in Italy, Africa, Greece, and in Asia Minor) “…and especially at Constantinople after the synthesis of East and West, of Greek, of Roman, of Syrian, and of Persian elements had been brought about as the outcome of the adoption of Christianity as the state religion”. For more than ten centuries these cultural streams and their many tributaries had flowed through Constantinople east and west and into the Slavonic world. This created a “fruitful traffic in ideas” between the Byzantine capita and the Christian and Moslem worlds. One sees in Byzantine art something “which links it, as far as aims and methods are concerned with the art of today..” We should not the judge Byzantine art by Greco-Roman Renaissance criteria it is this short-sighted approach to Byzantine art which, in the past, led the academic dogmatists to criticize it as a manifestation of decadence.

Painting & Stained Glass

The art of Constantinople had a far reaching and long lasting impact on the surrounding region. The period dates from the 5th through the 15th centuries. It includes art centred in the Ukraine and Russia as well.

The three "Golden Ages" of Byzantine Art

First, the Early Byzantine period, associated with the Emperor Justinian, dates from 527 to 726.

In 726 the iconoclastic controversy led to the destruction of many images.

The middle period began in 823, when Empress Theodora reinstated the veneration of icons and lasted until 1204, when Christian crusaders from the West occupied Constantinople.

The late Byzantine period began with the restoration of Byzantine rule in 1261, and ended when Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

Byzantine art continued to flourish in Russia, which succeeded Constantinople, as the centre of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The three "Golden Ages" of Byzantine Art

First, the Early Byzantine period, associated with the Emperor Justinian, dates from 527 to 726.

In 726 the iconoclastic controversy led to the destruction of many images.

The middle period began in 823, when Empress Theodora reinstated the veneration of icons and lasted until 1204, when Christian crusaders from the West occupied Constantinople.

The late Byzantine period began with the restoration of Byzantine rule in 1261, and ended when Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

Byzantine art continued to flourish in Russia, which succeeded Constantinople, as the centre of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

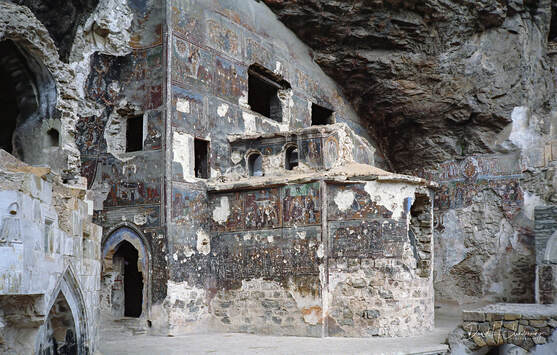

The First Sanctuaries - Paintings on Walls

|

|

|

The Engleistra (Place of Seclusion) of Agios Neofytos Monastery, 12th century. The paintings follow traditional Byzantine church decoration and were completed after 1197.

God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life. John 3:16

Tyrian purple (aka Royal purple or Imperial purple), is the colour historically used by Roman and Byzantine emperors

The color purple’s ties to kings and queens date back to ancient world, where it was prized for its bold hues and often reserved for the upper crust. The Persian king Cyrus adopted a purple tunic as his royal uniform, and some Roman emperors forbid their citizens from wearing purple clothing under penalty of death. Purple was especially revered in the Byzantine Empire. Its rulers wore flowing purple robes and signed their edicts in purple ink, and their children were described as being “born in the purple.”

The reason for purple’s regal reputation comes down to a simple case of supply and demand. For centuries, the purple dye trade was centered in the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre in modern day Lebanon. The Phoenicians’ “Tyrian purple” came from a species of sea snail now known as Bolinus brandaris, and it was so exceedingly rare that it became worth its weight in gold. To harvest it, dye-makers had to crack open the snail’s shell, extract a purple-producing mucus and expose it to sunlight for a precise amount of time. It took as many as 250,000 mollusks to yield just one ounce of usable dye, but the result was a vibrant and long-lasting shade of purple.

Clothes made from the dye were exorbitantly expensive—a pound of purple wool cost more than most people earned in a year—so they naturally became the calling card of the rich and powerful. It also didn’t hurt that Tyrian purple was said to resemble the color of clotted blood—a shade that supposedly carried divine connotations. The royal class’ purple monopoly finally waned after the fall of the Byzantine empire in the 15th century, but the color didn’t become more widely available until the 1850s, when the first synthetic dyes hit the market.

The reason for purple’s regal reputation comes down to a simple case of supply and demand. For centuries, the purple dye trade was centered in the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre in modern day Lebanon. The Phoenicians’ “Tyrian purple” came from a species of sea snail now known as Bolinus brandaris, and it was so exceedingly rare that it became worth its weight in gold. To harvest it, dye-makers had to crack open the snail’s shell, extract a purple-producing mucus and expose it to sunlight for a precise amount of time. It took as many as 250,000 mollusks to yield just one ounce of usable dye, but the result was a vibrant and long-lasting shade of purple.

Clothes made from the dye were exorbitantly expensive—a pound of purple wool cost more than most people earned in a year—so they naturally became the calling card of the rich and powerful. It also didn’t hurt that Tyrian purple was said to resemble the color of clotted blood—a shade that supposedly carried divine connotations. The royal class’ purple monopoly finally waned after the fall of the Byzantine empire in the 15th century, but the color didn’t become more widely available until the 1850s, when the first synthetic dyes hit the market.

Purple is a color intermediate between blue and red. It is similar to violet, but unlike violet, which is a spectral color with its own wavelength on the visible spectrum of light, purple is a composite color made by combining red and blue. According to surveys in Europe and the U.S., purple is the color most often associated with royalty, magic, mystery, and piety. When combined with pink, it is associated with eroticism, femininity, and seduction.

Purple was the color worn by Roman magistrates; it became the imperial color worn by the rulers of the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire, and later by Roman Catholic bishops. Similarly in Japan, the color is traditionally associated with the Emperor and aristocracy. The complementary color of purple is yellow.

In art, history and fashion

In prehistory and the ancient world: Tyrian purple

Purple first appeared in prehistoric art during the Neolithic era. The artists of Pech Merle cave and other Neolithic sites in France used sticks of manganese and hematite powder to draw and paint animals and the outlines of their own hands on the walls of their caves. These works have been dated to between 16,000 and 25,000 BC.

As early as the 15th century BC the citizens of Sidon and Tyre, two cities on the coast of Ancient Phoenicia, (present day Lebanon), were producing purple dye from a sea snail called the spiny dye-murex. Clothing colored with the Tyrian dye was mentioned in both the Iliad of Homer and the Aeneid of Virgil. The deep, rich purple dye made from this snail became known as Tyrian purple.

The process of making the dye was long, difficult and expensive. Thousands of the tiny snails had to be found, their shells cracked, the snail removed. Mountains of empty shells have been found at the ancient sites of Sidon and Tyre. The snails were left to soak, then a tiny gland was removed and the juice extracted and put in a basin, which was placed in the sunlight. There a remarkable transformation took place. In the sunlight the juice turned white, then yellow-green, then green, then violet, then a red which turned darker and darker. The process had to be stopped at exactly the right time to obtain the desired color, which could range from a bright crimson to a dark purple, the color of dried blood. Then either wool, linen or silk would be dyed. The exact hue varied between crimson and violet, but it was always rich, bright and lasting.

Tyrian purple became the color of kings, nobles, priests and magistrates all around the Mediterranean. It was mentioned in the Old Testament; In the Book of Exodus, God instructs Moses to have the Israelites bring him an offering including cloth “of blue, and purple, and scarlet.”, to be used in the curtains of the Tabernacle and the garments of priests. The term used for purple in the 4th-century Latin Vulgate version of the Bible passage is purpura or Tyrian purple. In the Iliad of Homer, the belt of Ajax is purple, and the tails of the horses of Trojan warriors are dipped in purple. In the Odyssey, the blankets on the wedding bed of Odysseus are purple. In the poems of Sappho (6th century BC) she celebrates the skill of the dyers of the Greek kingdom of Lydia who made purple footwear, and in the play of Aeschylus (525–456 BC), Queen Clytemnestra welcomes back her husband Agamemnon by decorating the palace with purple carpets. In 950 BC, King Solomon was reported to have brought artisans from Tyre to provide purple fabrics to decorate the Temple of Jerusalem.

Alexander the Great (when giving imperial audiences as the basileus of the Macedonian Empire), the basileus of the Seleucid Empire, and the kings of Ptolemaic Egypt all wore Tyrian purple.

The Roman custom of wearing purple togas may have come from the Etruscans; an Etruscan tomb painting from the 4th century BC shows a nobleman wearing a deep purple and embroidered toga.

In Ancient Rome, the Toga praetexta was an ordinary white toga with a broad purple stripe on its border. It was worn by freeborn Roman boys who had not yet come of age, curule magistrates, certain categories of priests, and a few other categories of citizens.

The Toga picta was solid purple, embroidered with gold. During the Roman Republic, it was worn by generals in their triumphs, and by the Praetor Urbanus when he rode in the chariot of the gods into the circus at the Ludi Apollinares. During the Empire, the toga picta was worn by magistrates giving public gladiatorial games, and by the consuls, as well as by the emperor on special occasions.

During the Roman Republic, when a triumph was held, the general being honored wore an entirely purple toga bordered in gold, and Roman Senators wore a toga with a purple stripe. However, during the Roman Empire, purple was more and more associated exclusively with the emperors and their officers. Suetonius claims that the early emperor Caligula had the King of Mauretania murdered for the splendour of his purple cloak, and that Nero forbade the use of certain purple dyes. In the late empire the sale of purple cloth became a state monopoly protected by the death penalty.

Jesus Christ, in the hours leading up to his crucifixion, was dressed in purple (πορφύρα: porphura) by the Roman garrison to mock his claim to be ‘King of the Jews’.

The actual color of Tyrian purple seems to have varied from a reddish to a bluish purple. According to the Roman writer Vitruvius, (1st century BC), the murex coming from northern waters, probably murex brandaris, produced a more bluish color than those of the south, probably murex trunculus. The most valued shades were said to be those closer to the color of dried blood, as seen in the mosaics of the robes of the Emperor Justinian in Ravenna. The chemical composition of the dye from the murex is close to that of the dye from indigo, and indigo was sometimes used to make a counterfeit Tyrian purple, a crime which was severely punished. What seems to have mattered about Tyrian purple was not its color, but its luster, richness, its resistance to weather and light, and its high price.

In modern times, Tyrian purple has been recreated, at great expense. When the German chemist, Paul Friedander, tried to recreate Tyrian purple in 2008, he needed twelve thousand mollusks to create 1.4 ounces of dye, enough to color a handkerchief. In the year 2000, a gram of Tyrian purple made from ten thousand mollusks according to the original formula, cost two thousand euros.

Purple in the Byzantine Empire and Carolingian Europe

Through the early Christian era, the rulers of the Byzantine Empire continued the use of purple as the imperial color, for diplomatic gifts, and even for imperial documents and the pages of the Bible. Gospel manuscripts were written in gold lettering on parchment that was colored Tyrian purple. Empresses gave birth in the Purple Chamber, and the emperors born there were known as “born to the purple,” to separate them from emperors who won or seized the title through political intrigue or military force. Bishops of the Byzantine church wore white robes with stripes of purple, while government officials wore squares of purple fabric to show their rank.

In western Europe, the Emperor Charlemagne was crowned in 800 wearing a mantle of Tyrian purple, and was buried in 814 in a shroud of the same color, which still exists (see below). However, after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the color lost its imperial status. The great dye works of Constantinople were destroyed, and gradually scarlet, made with dye from the cochineal insect, became the royal color in Europe.

The Middle Ages and Renaissance

In 1464, Pope Paul II decreed that cardinals should no longer wear Tyrian purple, and instead wear scarlet, from kermes and alum, since the dye from Byzantium was no longer available. Bishops and archbishops, of a lower status than cardinals, were assigned the color purple, but not the rich Tyrian purple. They wore cloth dyed first with the less expensive indigo blue, then overlaid with red made from kermes dye.

While purple was worn less frequently by Medieval and Renaissance kings and princes, it was worn by the professors of many of Europe’s new universities. Their robes were modeled after those of the clergy, and they often wore square violet or purple caps and robes, or black robes with purple trim. Purple robes were particularly worn by students of divinity.

Purple and violet also played an important part in the religious paintings of the Renaissance. Angels and the Virgin Mary were often portrayed wearing purple or violet robes.

18th and 19th centuries

In the 18th century, purple was still worn on occasion by Catherine the Great and other rulers, by bishops and, in lighter shades, by members of the aristocracy, but rarely by ordinary people, because of its high cost. But in the 19th century, that changed.

In 1856, an eighteen-year-old British chemistry student named William Henry Perkin was trying to make a synthetic quinine. His experiments produced instead the first synthetic aniline dye, a purple shade called mauveine, shortened simply to mauve. It took its name from the mallow flower, which is the same color. The new color quickly became fashionable, particularly after Queen Victoria wore a silk gown dyed with mauveine to the Royal Exhibition of 1862. Prior to Perkin’s discovery, mauve was a color which only the aristocracy and rich could afford to wear. Perkin developed an industrial process, built a factory, and produced the dye by the ton, so almost anyone could wear mauve. It was the first of a series of modern industrial dyes which completely transformed both the chemical industry and fashion. Purple was popular with the pre-Raphaelite painters in Britain, including Arthur Hughes, who loved bright colors and romantic scenes.

20th and 21st centuries

At the turn of the century, purple was a favorite color of the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, who flooded his pictures with sensual purples and violets.

In the 20th century, purple retained its historic connection with royalty; George VI (1896–1952), wore purple in his official portrait, and it was prominent in every feature of the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953, from the invitations to the stage design inside Westminster Abbey. But at the same time, it was becoming associated with social change; with the Women’s Suffrage movement for the right to vote for women in the early decades of the century, with Feminism in the 1970s, and with the psychedelic drug culture of the 1960s.

In the early 20th century, purple, green, and white were the colors of the Women’s Suffrage movement, which fought to win the right to vote for women, finally succeeding with the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. Later, in the 1970s, in a tribute to the Suffragettes, it became the color of the women’s liberation movement.

In the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, prisoners who were members of non-conformist religious groups, such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, were required to wear a purple triangle.

During the 1960s and early 1970s, it was also associated with counterculture, psychedelics, and musicians like Jimi Hendrix with his 1967 song “Purple Haze”, or the English rock band of Deep Purple which formed in 1968. Later, in the 1980s, it was featured in the song and album Purple Rain (1984) by the American musician Prince.

The Purple Rain Protest was a protest against apartheid that took place in Cape Town, South Africa on 2 September 1989, in which a police water cannon with purple dye sprayed thousands of demonstrators. This led to the slogan The Purple Shall Govern.

The violet or purple necktie became very popular at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, particularly among political and business leaders. It combined the assertiveness and confidence of a red necktie with the sense of peace and cooperation of a blue necktie, and it went well with the blue business suit worn by most national and corporate leaders.

China

In ancient China, purple was obtained not through the Mediterranean mollusc, but purple gromwell. The dye obtained did not easily adhere to fabrics, making purple fabrics expensive. Purple became a fashionable colour in the state of Qi (齊) because its ruler developed a preference for it. As a result, the price of a purple spoke of fabric was in excess of five times that of a plain spoke. His minister, Guan Zhong (管仲) eventually convinced him to relinquish this preference.

Purple was regarded as a secondary colour in ancient China. In classical times, secondary colours were not as highly prized as the five primary colours of the Chinese spectrum, and purple was used to allude to impropriety, compared to crimson, which was deemed a primary colour and thus symbolized legitimacy. Nevertheless, by the 6th Century, purple was ranked above crimson. Several changes to the ranks of colours occurred after that time.

Source From Wikipedia

Purple was the color worn by Roman magistrates; it became the imperial color worn by the rulers of the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire, and later by Roman Catholic bishops. Similarly in Japan, the color is traditionally associated with the Emperor and aristocracy. The complementary color of purple is yellow.

In art, history and fashion

In prehistory and the ancient world: Tyrian purple

Purple first appeared in prehistoric art during the Neolithic era. The artists of Pech Merle cave and other Neolithic sites in France used sticks of manganese and hematite powder to draw and paint animals and the outlines of their own hands on the walls of their caves. These works have been dated to between 16,000 and 25,000 BC.

As early as the 15th century BC the citizens of Sidon and Tyre, two cities on the coast of Ancient Phoenicia, (present day Lebanon), were producing purple dye from a sea snail called the spiny dye-murex. Clothing colored with the Tyrian dye was mentioned in both the Iliad of Homer and the Aeneid of Virgil. The deep, rich purple dye made from this snail became known as Tyrian purple.

The process of making the dye was long, difficult and expensive. Thousands of the tiny snails had to be found, their shells cracked, the snail removed. Mountains of empty shells have been found at the ancient sites of Sidon and Tyre. The snails were left to soak, then a tiny gland was removed and the juice extracted and put in a basin, which was placed in the sunlight. There a remarkable transformation took place. In the sunlight the juice turned white, then yellow-green, then green, then violet, then a red which turned darker and darker. The process had to be stopped at exactly the right time to obtain the desired color, which could range from a bright crimson to a dark purple, the color of dried blood. Then either wool, linen or silk would be dyed. The exact hue varied between crimson and violet, but it was always rich, bright and lasting.

Tyrian purple became the color of kings, nobles, priests and magistrates all around the Mediterranean. It was mentioned in the Old Testament; In the Book of Exodus, God instructs Moses to have the Israelites bring him an offering including cloth “of blue, and purple, and scarlet.”, to be used in the curtains of the Tabernacle and the garments of priests. The term used for purple in the 4th-century Latin Vulgate version of the Bible passage is purpura or Tyrian purple. In the Iliad of Homer, the belt of Ajax is purple, and the tails of the horses of Trojan warriors are dipped in purple. In the Odyssey, the blankets on the wedding bed of Odysseus are purple. In the poems of Sappho (6th century BC) she celebrates the skill of the dyers of the Greek kingdom of Lydia who made purple footwear, and in the play of Aeschylus (525–456 BC), Queen Clytemnestra welcomes back her husband Agamemnon by decorating the palace with purple carpets. In 950 BC, King Solomon was reported to have brought artisans from Tyre to provide purple fabrics to decorate the Temple of Jerusalem.

Alexander the Great (when giving imperial audiences as the basileus of the Macedonian Empire), the basileus of the Seleucid Empire, and the kings of Ptolemaic Egypt all wore Tyrian purple.

The Roman custom of wearing purple togas may have come from the Etruscans; an Etruscan tomb painting from the 4th century BC shows a nobleman wearing a deep purple and embroidered toga.

In Ancient Rome, the Toga praetexta was an ordinary white toga with a broad purple stripe on its border. It was worn by freeborn Roman boys who had not yet come of age, curule magistrates, certain categories of priests, and a few other categories of citizens.

The Toga picta was solid purple, embroidered with gold. During the Roman Republic, it was worn by generals in their triumphs, and by the Praetor Urbanus when he rode in the chariot of the gods into the circus at the Ludi Apollinares. During the Empire, the toga picta was worn by magistrates giving public gladiatorial games, and by the consuls, as well as by the emperor on special occasions.

During the Roman Republic, when a triumph was held, the general being honored wore an entirely purple toga bordered in gold, and Roman Senators wore a toga with a purple stripe. However, during the Roman Empire, purple was more and more associated exclusively with the emperors and their officers. Suetonius claims that the early emperor Caligula had the King of Mauretania murdered for the splendour of his purple cloak, and that Nero forbade the use of certain purple dyes. In the late empire the sale of purple cloth became a state monopoly protected by the death penalty.

Jesus Christ, in the hours leading up to his crucifixion, was dressed in purple (πορφύρα: porphura) by the Roman garrison to mock his claim to be ‘King of the Jews’.

The actual color of Tyrian purple seems to have varied from a reddish to a bluish purple. According to the Roman writer Vitruvius, (1st century BC), the murex coming from northern waters, probably murex brandaris, produced a more bluish color than those of the south, probably murex trunculus. The most valued shades were said to be those closer to the color of dried blood, as seen in the mosaics of the robes of the Emperor Justinian in Ravenna. The chemical composition of the dye from the murex is close to that of the dye from indigo, and indigo was sometimes used to make a counterfeit Tyrian purple, a crime which was severely punished. What seems to have mattered about Tyrian purple was not its color, but its luster, richness, its resistance to weather and light, and its high price.

In modern times, Tyrian purple has been recreated, at great expense. When the German chemist, Paul Friedander, tried to recreate Tyrian purple in 2008, he needed twelve thousand mollusks to create 1.4 ounces of dye, enough to color a handkerchief. In the year 2000, a gram of Tyrian purple made from ten thousand mollusks according to the original formula, cost two thousand euros.

Purple in the Byzantine Empire and Carolingian Europe

Through the early Christian era, the rulers of the Byzantine Empire continued the use of purple as the imperial color, for diplomatic gifts, and even for imperial documents and the pages of the Bible. Gospel manuscripts were written in gold lettering on parchment that was colored Tyrian purple. Empresses gave birth in the Purple Chamber, and the emperors born there were known as “born to the purple,” to separate them from emperors who won or seized the title through political intrigue or military force. Bishops of the Byzantine church wore white robes with stripes of purple, while government officials wore squares of purple fabric to show their rank.

In western Europe, the Emperor Charlemagne was crowned in 800 wearing a mantle of Tyrian purple, and was buried in 814 in a shroud of the same color, which still exists (see below). However, after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the color lost its imperial status. The great dye works of Constantinople were destroyed, and gradually scarlet, made with dye from the cochineal insect, became the royal color in Europe.

The Middle Ages and Renaissance

In 1464, Pope Paul II decreed that cardinals should no longer wear Tyrian purple, and instead wear scarlet, from kermes and alum, since the dye from Byzantium was no longer available. Bishops and archbishops, of a lower status than cardinals, were assigned the color purple, but not the rich Tyrian purple. They wore cloth dyed first with the less expensive indigo blue, then overlaid with red made from kermes dye.

While purple was worn less frequently by Medieval and Renaissance kings and princes, it was worn by the professors of many of Europe’s new universities. Their robes were modeled after those of the clergy, and they often wore square violet or purple caps and robes, or black robes with purple trim. Purple robes were particularly worn by students of divinity.

Purple and violet also played an important part in the religious paintings of the Renaissance. Angels and the Virgin Mary were often portrayed wearing purple or violet robes.

18th and 19th centuries

In the 18th century, purple was still worn on occasion by Catherine the Great and other rulers, by bishops and, in lighter shades, by members of the aristocracy, but rarely by ordinary people, because of its high cost. But in the 19th century, that changed.

In 1856, an eighteen-year-old British chemistry student named William Henry Perkin was trying to make a synthetic quinine. His experiments produced instead the first synthetic aniline dye, a purple shade called mauveine, shortened simply to mauve. It took its name from the mallow flower, which is the same color. The new color quickly became fashionable, particularly after Queen Victoria wore a silk gown dyed with mauveine to the Royal Exhibition of 1862. Prior to Perkin’s discovery, mauve was a color which only the aristocracy and rich could afford to wear. Perkin developed an industrial process, built a factory, and produced the dye by the ton, so almost anyone could wear mauve. It was the first of a series of modern industrial dyes which completely transformed both the chemical industry and fashion. Purple was popular with the pre-Raphaelite painters in Britain, including Arthur Hughes, who loved bright colors and romantic scenes.

20th and 21st centuries

At the turn of the century, purple was a favorite color of the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, who flooded his pictures with sensual purples and violets.

In the 20th century, purple retained its historic connection with royalty; George VI (1896–1952), wore purple in his official portrait, and it was prominent in every feature of the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953, from the invitations to the stage design inside Westminster Abbey. But at the same time, it was becoming associated with social change; with the Women’s Suffrage movement for the right to vote for women in the early decades of the century, with Feminism in the 1970s, and with the psychedelic drug culture of the 1960s.

In the early 20th century, purple, green, and white were the colors of the Women’s Suffrage movement, which fought to win the right to vote for women, finally succeeding with the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. Later, in the 1970s, in a tribute to the Suffragettes, it became the color of the women’s liberation movement.

In the concentration camps of Nazi Germany, prisoners who were members of non-conformist religious groups, such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, were required to wear a purple triangle.

During the 1960s and early 1970s, it was also associated with counterculture, psychedelics, and musicians like Jimi Hendrix with his 1967 song “Purple Haze”, or the English rock band of Deep Purple which formed in 1968. Later, in the 1980s, it was featured in the song and album Purple Rain (1984) by the American musician Prince.

The Purple Rain Protest was a protest against apartheid that took place in Cape Town, South Africa on 2 September 1989, in which a police water cannon with purple dye sprayed thousands of demonstrators. This led to the slogan The Purple Shall Govern.

The violet or purple necktie became very popular at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, particularly among political and business leaders. It combined the assertiveness and confidence of a red necktie with the sense of peace and cooperation of a blue necktie, and it went well with the blue business suit worn by most national and corporate leaders.

China

In ancient China, purple was obtained not through the Mediterranean mollusc, but purple gromwell. The dye obtained did not easily adhere to fabrics, making purple fabrics expensive. Purple became a fashionable colour in the state of Qi (齊) because its ruler developed a preference for it. As a result, the price of a purple spoke of fabric was in excess of five times that of a plain spoke. His minister, Guan Zhong (管仲) eventually convinced him to relinquish this preference.

Purple was regarded as a secondary colour in ancient China. In classical times, secondary colours were not as highly prized as the five primary colours of the Chinese spectrum, and purple was used to allude to impropriety, compared to crimson, which was deemed a primary colour and thus symbolized legitimacy. Nevertheless, by the 6th Century, purple was ranked above crimson. Several changes to the ranks of colours occurred after that time.

Source From Wikipedia

Tyrian purple en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyrian_purple

Variations of Byzantium Colour en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantium_(color)

In the Byzantium Style

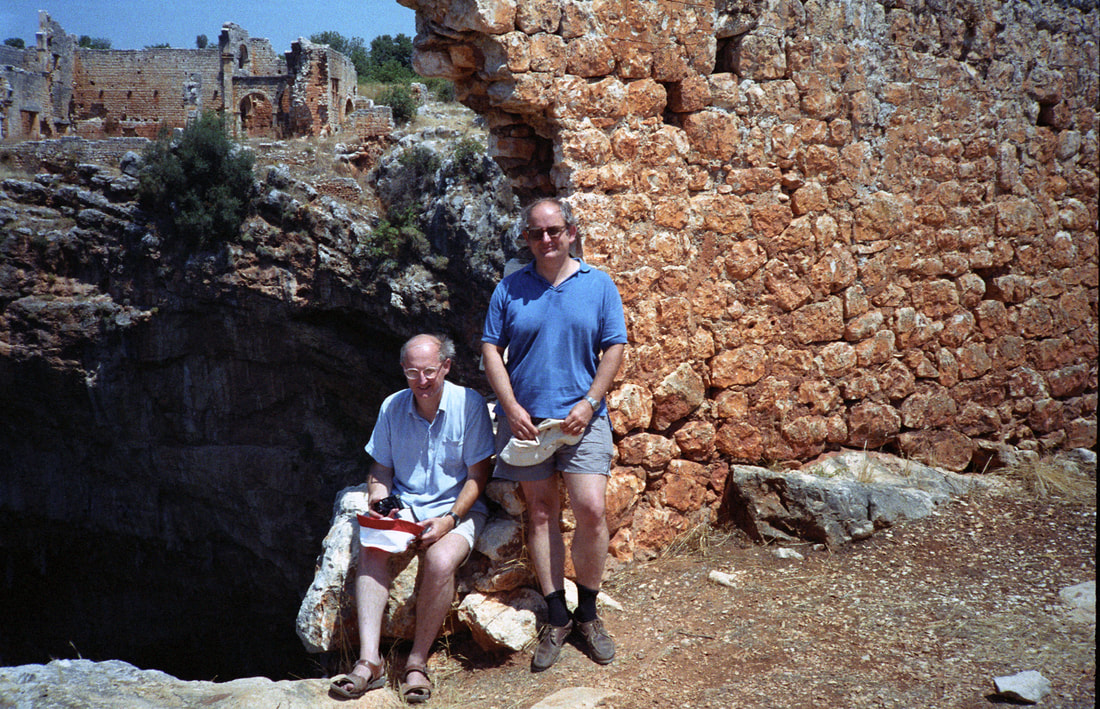

Negative scanned film used, circa. 1988-89.

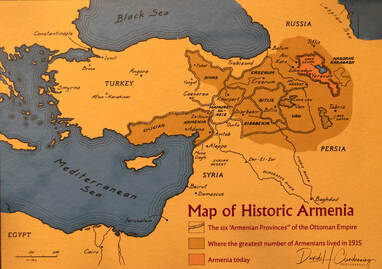

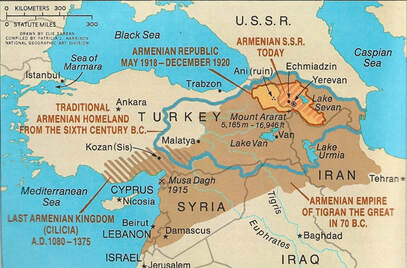

Map of Armenian History - Region of Conflict

|

Heritage of Eastern Turkey

The best preserved Islamic palace in eastern Turkey is Ishak Pasa. Located amid the hauntingly alluring and desolate landscape of Dogubayazit, it is one of the most outlandish buildings in Turkey. Built on a dominant rocky spur and visible from afar, the fortified palace was strategically positioned one the border of Turkey and Iran, to take advantage of the Silk Route, whose caravaners had no optioned but to pay tribute to the palace in return for a safe passage along the Tabriz-Erzurum road. A glance at the palace will leave no doubt that the Ishak Pasa and his family grew rich from this enterprise. The palace flourished for about four centuries, from the fourteenth century until the conflicts with Russia in 1828-29. Ishak became a Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire in 1789 and began building the palace, though his son Mahmut Pasa may have completed it. |

Christianity continues to struggle in Turkey

Bulgarian St Stephen Church also known as the Bulgarian Iron Church, is a Bulgarian Orthodox church in Balat, Istanbul, Turkey. It is famous for being made of prefabricated cast iron elements in the neo-Byzantine style. Back in 1871 this church was constructed from cast-iron pieces shipped down the Danube and across the Black Sea from Vienna on 100 barges, the idea was extremely novel. The congregation comprised members of the Bulgarian Orthodox Exarchate (Bulgarian Orthodox Church0, which broke away from the Greek Ecumenical Orthodox Patriarchate in 1872.

Rome in the East: The Art of Byzantium

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

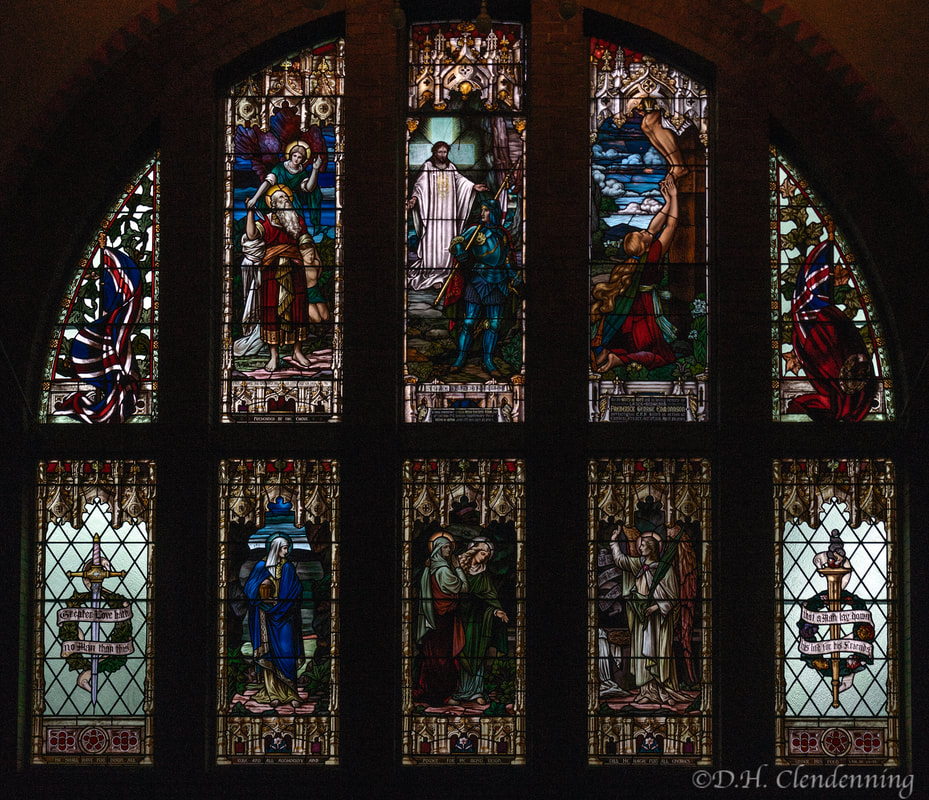

Byzantine Revival style in Canada

St. Anne's Anglican Church National Historic Site of Canada, Toronto.

One of Canada's artistic lost treasures

Built in 1907-1908 in the Byzantine Revival style the church contains a remarkable cycle of paintings by ten prominent Canadian Artists, including three (J.E.H. MacDonald, Fred Varley and Frank Carmichael) from the famous Group of Seven. The result was their only religious art.

St. Anne, of course, has no iconostasis (screen bearing icons, separating the sanctuary of many Eastern churches from the nave.), and this changes the relationship of the paintings to the space. In St. Anne's there is an emphatic stress of the apsidal chancel with the sequence of five trapezoidal panels above the window and two more above the organ pipes. Alongside these seven scenes illustrating events in the Gospels, the four major scenes on the triangular pendentives illustrate moments in Jesus's life (nativity, crucifixion, resurrection and ascension). They are unquestionably the highlight of the iconography,

The elaborate interior mural decoration, designed by J. E.H. MacDonald, cover the walls and ceiling of the apse, the main arches, the pendentives and the central dome. The cycle combines narrative scenes, written texts, as well as decorative plasterwork and detailing accentuating the architectural lines of the building. Official recognition refers to the building and its interior decorative work on its legal lot.

Its cycle of painting belongs to the revival of mural decoration that emerged int he last quarter of the 19th century and is a manifestation of the Arts and Crafts movement which sought to ally architecture with the sister arts of painting and sculpture.

St. Anne's decorative cycle draws upon the motifs, colours and the artistic conventions of Byzantine art while adapting their character to reflect a contemporary Canaidan setting. The works are integral to the church's architectural style.

The original decision to build in a Byzantine style reflected the support for an ecumenical movement that advocated unification with other Protestant denominations. Architect W. Ford Howland's design was intended to evoke the early Byzantine period, before the Christain church had split into its subsequent numerous denominations.

One of Canada's artistic lost treasures

Built in 1907-1908 in the Byzantine Revival style the church contains a remarkable cycle of paintings by ten prominent Canadian Artists, including three (J.E.H. MacDonald, Fred Varley and Frank Carmichael) from the famous Group of Seven. The result was their only religious art.

St. Anne, of course, has no iconostasis (screen bearing icons, separating the sanctuary of many Eastern churches from the nave.), and this changes the relationship of the paintings to the space. In St. Anne's there is an emphatic stress of the apsidal chancel with the sequence of five trapezoidal panels above the window and two more above the organ pipes. Alongside these seven scenes illustrating events in the Gospels, the four major scenes on the triangular pendentives illustrate moments in Jesus's life (nativity, crucifixion, resurrection and ascension). They are unquestionably the highlight of the iconography,

The elaborate interior mural decoration, designed by J. E.H. MacDonald, cover the walls and ceiling of the apse, the main arches, the pendentives and the central dome. The cycle combines narrative scenes, written texts, as well as decorative plasterwork and detailing accentuating the architectural lines of the building. Official recognition refers to the building and its interior decorative work on its legal lot.

Its cycle of painting belongs to the revival of mural decoration that emerged int he last quarter of the 19th century and is a manifestation of the Arts and Crafts movement which sought to ally architecture with the sister arts of painting and sculpture.

St. Anne's decorative cycle draws upon the motifs, colours and the artistic conventions of Byzantine art while adapting their character to reflect a contemporary Canaidan setting. The works are integral to the church's architectural style.

The original decision to build in a Byzantine style reflected the support for an ecumenical movement that advocated unification with other Protestant denominations. Architect W. Ford Howland's design was intended to evoke the early Byzantine period, before the Christain church had split into its subsequent numerous denominations.

Apse or Chancel Ceiling

The apse or chancel ceiling has a background of blue over which is a vine leaf pattern with clusters of grapes in gold leaf. On the ceiling are circular decorations including symbols such as the Three of Life guarded by the two cherubim, and the Lamb. The alpha (A) and the Omega (W) signify Christ as the beginning and the end. Also present are the letters I and C, which are the first and last letters of Jesus in Greek, and C and R, which are the initials letters of Christ in Greek. These combined with the Greek Word NIKE (conquers) give "Jesus Christ conquers". These are ancient Christain symbols. Between the chancel windows are circular plaster reliefs depicting a peacock and an urn by the sculptors Frances Loring and Florence Wyle. The central mosaic work added in 1960 was the work of Nicholas Kavakonis. The stained glass windows in the chancel came from the original 1862 church. St. Anne's was designated a National Historic Site in 1997.

The apse or chancel ceiling has a background of blue over which is a vine leaf pattern with clusters of grapes in gold leaf. On the ceiling are circular decorations including symbols such as the Three of Life guarded by the two cherubim, and the Lamb. The alpha (A) and the Omega (W) signify Christ as the beginning and the end. Also present are the letters I and C, which are the first and last letters of Jesus in Greek, and C and R, which are the initials letters of Christ in Greek. These combined with the Greek Word NIKE (conquers) give "Jesus Christ conquers". These are ancient Christain symbols. Between the chancel windows are circular plaster reliefs depicting a peacock and an urn by the sculptors Frances Loring and Florence Wyle. The central mosaic work added in 1960 was the work of Nicholas Kavakonis. The stained glass windows in the chancel came from the original 1862 church. St. Anne's was designated a National Historic Site in 1997.

Loss of Historic St. Anne's Anglican Church (Est. 1908, Dstr. 2024) in Toronto' catastrophe for Canadian architecture on June 9, 2024

Globe & Mail, June 10, 2024

www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-st-annes-anglican-church-was-a-place-of-unique-significance-but-now/

National Historic Site: www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=12681

St. Anne’s Anglican Church was a place of unique significance. And now it is largely gone. A fire early Sunday devastated the national historic site in Toronto, consuming decorative paintings by members of the Group of Seven and leaving much of the building in ashes.

“It’s a catastrophe for Canadian architecture, Canadian art and Canadian heritage,” the Concordia University architectural historian Peter Coffman said. “This was a unique building that could only have happened in Canada.”

While the cause of the fire is still unknown, the loss of St. Anne’s reflects widespread challenges for Canadian heritage sites and particularly churches. Social and demographic changes have left many such structures underused and in poor condition, while government funding for their maintenance is scarce.

That lack of resources would not have surprised J.E.H. MacDonald. “Canada seemingly gets her walls painted, but not decorated,” the artist and Group of Seven member wrote in a 1925 article about St. Anne’s. “Giotto would be out of work among us, and Michelangelo would move from Toronto to New York.”

St. Anne’s proved to be an unlikely exception.

The Anglican congregation was established in what was the village of Brockton in 1862. By 1907, the fast-growing church held a design competition for a new building; the winner was architect William Ford Howland, with a plan in the neo-Byzantine style. In 1908, it was completed with a modest exterior mostly of yellow brick. A pair of towers flanked its three arched doorways and five recessed stilted arches.

Yet Howland’s design was a bold choice by Reverend Lawrence Skey. “For the Anglican Church in Canada of the time, it was spectacularly radical,” said Prof. Coffman, author of a paper on the church’s history. The Anglican house style was Gothic; most Anglican churches were accordingly long, tall, ornate and carried an air of medieval England.

This one was modelled after the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. A 17-metre-wide, 21-metre-tall dome formed the centre of the building; here the reverend could make eye contact with the congregants while he delivered his sermon. “This was a church as a forum,” Prof. Coffman said. “Skey was explicitly turning his back on two generations of church building,” rejecting Gothic frippery and the “high church” emphasis on ritual.

St. Anne’s at first was almost without decoration, but in 1923, Skey raised the funds to hire architect William Rae and the artist J.E.H. MacDonald. MacDonald was another rebellious choice: A commercial artist and a member of the newly formed Group of Seven, he had no experience with religious art. (Skey had probably met MacDonald drinking at the Arts and Letters Club where they were both members.)

MacDonald led nine other artists including the Group’s Franklin Carmichael and Frederick Varley, as well as MacDonald’s 18-year-old son, Thoreau. They painted an elaborate array of symbolic ornaments on a field of aquamarine and gold, and frescoes drawing from Byzantine and Renaissance Christian art.

Varley painted images of Old Testament prophets into the cornices of the dome, which collapsed during the fire. He also painted the Nativity, depicting himself as a shepherd, while MacDonald painted the Crucifixion on one of the pendentives, the triangular elements where the dome intersected with the column. MacDonald also commissioned Toronto sculptors Florence Wyle and Frances Loring to contribute reliefs of the four apostles.

Skey’s congregants were largely working class; some would have laboured at the Cadbury chocolate factory across the street, which then as now towered over the church. Inside the dome, they now could look up and read a passage from the Gospel of St. Matthew: “Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.”

Sarah Milroy, director of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ont., recalls the church as a cozy space with the murals painted in a relatively informal style that evoked the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain, which aspired to bring beauty to everyday life. “I remember the extraordinary warmth and congeniality of the space,” she said. “It was a real Arts and Crafts gem, one of the most important cultural sites in Toronto.”

A 1937 article in The Globe and Mail called St. Anne’s “one of the most beautiful in Canada.” A further round of renovations in the 1960s added Byzantine-themed mosaics. However, the congregation declined rapidly in size and influence. Its neighbourhood in what was now central Toronto became increasingly Catholic and less religious. By 2000, the congregation had fewer than 100 members and was hosting a fundraiser to repair problems with the roof and structure.

The situation remained difficult in recent years. The church’s parish hall, located behind the sanctuary, was rented out for many cultural events, and in 2022, the church sought permission to separate that building from the rest of the property with an eye to selling it.

Diane Chin, chair of the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario, said that many churches find themselves in similar circumstances, and will need to remake their facilities “as hubs for the community.” “Bringing in cultural events, seniors’ activities, feeding the homeless – I think that’s how churches can succeed in their reinvention and restoration,” she said.

The United Church of Canada is collaborating with a development organization, Kindred Works, on dozens of such projects; the Trinity Centres Foundation also advises faith communities on repurposing their buildings.

However, straightforward maintenance and restoration of buildings remain the responsibility of individual organizations. Some provinces provide tax credits or grant programs to support such work; in Ontario there are few, and in Toronto, they apply only to commercial and industrial properties. Ms. Chin said the ACO is lobbying for such programs to be expanded.

It is unclear for now whether such programs would have kept St. Anne’s intact, along with the art within – the only religious works by some of Canada’s most significant artists. But there may be an opportunity to test Canada’s resources for heritage restoration. On Sunday, both Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow and the church’s current rector, Father Don Beyers, vowed to rebuild the structure.

But Prof. Coffman doubted it could be the same saying, “It really is irreplaceable. It’s a testament to how fragile our most important heritage can be.”

Globe & Mail, June 10, 2024

www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-st-annes-anglican-church-was-a-place-of-unique-significance-but-now/

National Historic Site: www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=12681

St. Anne’s Anglican Church was a place of unique significance. And now it is largely gone. A fire early Sunday devastated the national historic site in Toronto, consuming decorative paintings by members of the Group of Seven and leaving much of the building in ashes.

“It’s a catastrophe for Canadian architecture, Canadian art and Canadian heritage,” the Concordia University architectural historian Peter Coffman said. “This was a unique building that could only have happened in Canada.”

While the cause of the fire is still unknown, the loss of St. Anne’s reflects widespread challenges for Canadian heritage sites and particularly churches. Social and demographic changes have left many such structures underused and in poor condition, while government funding for their maintenance is scarce.

That lack of resources would not have surprised J.E.H. MacDonald. “Canada seemingly gets her walls painted, but not decorated,” the artist and Group of Seven member wrote in a 1925 article about St. Anne’s. “Giotto would be out of work among us, and Michelangelo would move from Toronto to New York.”

St. Anne’s proved to be an unlikely exception.

The Anglican congregation was established in what was the village of Brockton in 1862. By 1907, the fast-growing church held a design competition for a new building; the winner was architect William Ford Howland, with a plan in the neo-Byzantine style. In 1908, it was completed with a modest exterior mostly of yellow brick. A pair of towers flanked its three arched doorways and five recessed stilted arches.

Yet Howland’s design was a bold choice by Reverend Lawrence Skey. “For the Anglican Church in Canada of the time, it was spectacularly radical,” said Prof. Coffman, author of a paper on the church’s history. The Anglican house style was Gothic; most Anglican churches were accordingly long, tall, ornate and carried an air of medieval England.

This one was modelled after the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. A 17-metre-wide, 21-metre-tall dome formed the centre of the building; here the reverend could make eye contact with the congregants while he delivered his sermon. “This was a church as a forum,” Prof. Coffman said. “Skey was explicitly turning his back on two generations of church building,” rejecting Gothic frippery and the “high church” emphasis on ritual.

St. Anne’s at first was almost without decoration, but in 1923, Skey raised the funds to hire architect William Rae and the artist J.E.H. MacDonald. MacDonald was another rebellious choice: A commercial artist and a member of the newly formed Group of Seven, he had no experience with religious art. (Skey had probably met MacDonald drinking at the Arts and Letters Club where they were both members.)

MacDonald led nine other artists including the Group’s Franklin Carmichael and Frederick Varley, as well as MacDonald’s 18-year-old son, Thoreau. They painted an elaborate array of symbolic ornaments on a field of aquamarine and gold, and frescoes drawing from Byzantine and Renaissance Christian art.

Varley painted images of Old Testament prophets into the cornices of the dome, which collapsed during the fire. He also painted the Nativity, depicting himself as a shepherd, while MacDonald painted the Crucifixion on one of the pendentives, the triangular elements where the dome intersected with the column. MacDonald also commissioned Toronto sculptors Florence Wyle and Frances Loring to contribute reliefs of the four apostles.

Skey’s congregants were largely working class; some would have laboured at the Cadbury chocolate factory across the street, which then as now towered over the church. Inside the dome, they now could look up and read a passage from the Gospel of St. Matthew: “Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.”

Sarah Milroy, director of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ont., recalls the church as a cozy space with the murals painted in a relatively informal style that evoked the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain, which aspired to bring beauty to everyday life. “I remember the extraordinary warmth and congeniality of the space,” she said. “It was a real Arts and Crafts gem, one of the most important cultural sites in Toronto.”

A 1937 article in The Globe and Mail called St. Anne’s “one of the most beautiful in Canada.” A further round of renovations in the 1960s added Byzantine-themed mosaics. However, the congregation declined rapidly in size and influence. Its neighbourhood in what was now central Toronto became increasingly Catholic and less religious. By 2000, the congregation had fewer than 100 members and was hosting a fundraiser to repair problems with the roof and structure.

The situation remained difficult in recent years. The church’s parish hall, located behind the sanctuary, was rented out for many cultural events, and in 2022, the church sought permission to separate that building from the rest of the property with an eye to selling it.

Diane Chin, chair of the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario, said that many churches find themselves in similar circumstances, and will need to remake their facilities “as hubs for the community.” “Bringing in cultural events, seniors’ activities, feeding the homeless – I think that’s how churches can succeed in their reinvention and restoration,” she said.

The United Church of Canada is collaborating with a development organization, Kindred Works, on dozens of such projects; the Trinity Centres Foundation also advises faith communities on repurposing their buildings.

However, straightforward maintenance and restoration of buildings remain the responsibility of individual organizations. Some provinces provide tax credits or grant programs to support such work; in Ontario there are few, and in Toronto, they apply only to commercial and industrial properties. Ms. Chin said the ACO is lobbying for such programs to be expanded.

It is unclear for now whether such programs would have kept St. Anne’s intact, along with the art within – the only religious works by some of Canada’s most significant artists. But there may be an opportunity to test Canada’s resources for heritage restoration. On Sunday, both Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow and the church’s current rector, Father Don Beyers, vowed to rebuild the structure.

But Prof. Coffman doubted it could be the same saying, “It really is irreplaceable. It’s a testament to how fragile our most important heritage can be.”