Christian Iconography

Icons of the Hellenic World - Greek and Byzantium iconography

Iconograpnhy

iconography: the visual images and symbols used in a work of art or the study or interpretation of these: the conventional iconography of Christian art.

Visual Art - Iconography

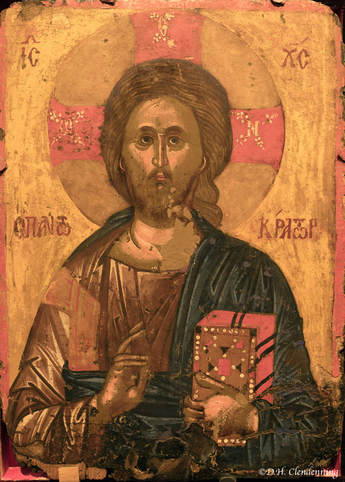

The term comes from the Greek word ikon meaning image. An icon was originally a picture of Christ on a panel used as an object of devotion in the Eastern Orthodox Church from at least the seventh century on. Hence the term icon has come to be attached to any object or image that is outstanding or has a special meaning attached to it.

Icons are most commonly created with tempera paint on wood panels but they can be made using a variety of materials such as metal casting, mosaics, textile works, and frescos. The oldest icons date from the 5th and 6th centuries; and after suffering a temporary setback as a result of the iconoclastic movement they played an increasingly important role throughout the history of Byzantine art, reaching their apogee at the time of the Empire's final collapse.

The icon as a Sacred Image

The icon is an archaeological record and a work of art. The Orthodox Church understands the icon to be a sacred image depicting a higher, divine reality. It is a visible reflection of an invisible realm in which all these qualities are simultaneously present. For the past two thousand years the icon has remained a constant image of the eternal and divine.

An icon as a sacred image depends on the continuous and accurate replication based on a prototype. The icon painter copies from the prototype as accurately as the medieval scribe and illuminator made the exquisite copies of the Bible. Just as the faithful would not alter the core meaning of a sacred text, such as the Bible, the same hold true of the icon.

Over time, regional differences and cultural influence allowed for stylistic changes in the icons, each becoming its own distinct work of art while remaining surprisingly constant in its purpose. The icon, no matter the artistic influence, links the viewer directly to the dawn of Christianity when many of the early practitioners were illiterate and relied on visual information to understand the World.

In order to understand the language of the icon the viewer must desire to meet with this reality: to enter into it, the viewer needs to learn to read the icon. The icon must not be regarded as a simple illustration of the Gospels or other theological texts. Visual form and Word are fused together to penetrate an alternate reality.

An iconography is a particular range or system of types of image used by an artist or artists to convey particular meanings. For example in Christian religious painting there is an iconography of images such as the lamb which represents Christ, or the dove which represents the Holy Spirit. In the iconography of classical myth however, the presence of a dove would suggest that any woman also present would be the goddess Aphrodite or Venus, so the meanings of particular images can depend on context.

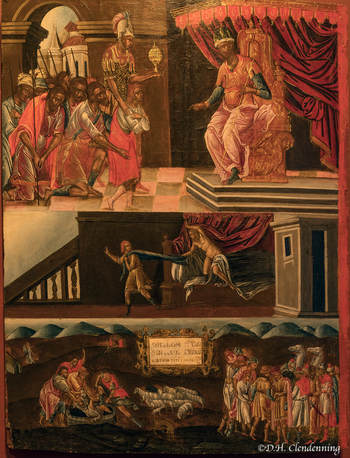

The production of these small images, painted on wooden panels in an egg-yolk medium, was promoted after the 13th century by a whole series of circumstances. In the first place the practice grew up of hanging at least two rows of icons on the iconostasis (screen bearing icons, separating the sanctuary of many Eastern churches from the nave), considerably increasing the number required; the larger icons in the lower tier represented Christ, or the Virgin and Child, or the patron saint of the church, while on the upper tier were icons of the liturgical festivals, the Deisis or scenes from the lives of saints. A second factor was that in time of disturbance or danger to the Faith - as a result, for example, of the victories of the infidels - one of the ways in which ordinary people could seek reassurance and express their confidence and hope was to have in their homes images of Christ, the Virgin or the various saints to which they could address their prayers more easily and more frequently than in church. Gradually, therefore, each family came to have their own icons, varying inequality and costliness according to their resources. Theses icons now provide his historian with a mass of evidence, enabling him to observe the long continuance of traditional forms.

The icon-painters were not much given to innovation: they sought to reassure the faithful that the image would preserve its efficacy and power, and the best way of achieving this was to maintain the traditional patterns which were familiar to all. As time went on, however, other influences came into play alongside this conservative trend. In Eastern Christendom, where much of the population had fallen under the Turkish yoke while other areas remained independent, there was not the same cohesion aa before 1453, nor the same close links with the capital. In Crete, and later even more strongly in the Ionian Island, which still belonged to Venice, Italian influences were powerfully felt. In Russian and elsewhere artist expressed their religious ideal in forms which were no longer wholly Byzantine.

Iconography (or iconology) is also the academic discipline of the study of images in art and their meanings.

Source: Museum of Russian Icons and www.tate.org/art-terms/iconography

The term comes from the Greek word ikon meaning image. An icon was originally a picture of Christ on a panel used as an object of devotion in the Eastern Orthodox Church from at least the seventh century on. Hence the term icon has come to be attached to any object or image that is outstanding or has a special meaning attached to it.

Icons are most commonly created with tempera paint on wood panels but they can be made using a variety of materials such as metal casting, mosaics, textile works, and frescos. The oldest icons date from the 5th and 6th centuries; and after suffering a temporary setback as a result of the iconoclastic movement they played an increasingly important role throughout the history of Byzantine art, reaching their apogee at the time of the Empire's final collapse.

The icon as a Sacred Image

The icon is an archaeological record and a work of art. The Orthodox Church understands the icon to be a sacred image depicting a higher, divine reality. It is a visible reflection of an invisible realm in which all these qualities are simultaneously present. For the past two thousand years the icon has remained a constant image of the eternal and divine.

An icon as a sacred image depends on the continuous and accurate replication based on a prototype. The icon painter copies from the prototype as accurately as the medieval scribe and illuminator made the exquisite copies of the Bible. Just as the faithful would not alter the core meaning of a sacred text, such as the Bible, the same hold true of the icon.

Over time, regional differences and cultural influence allowed for stylistic changes in the icons, each becoming its own distinct work of art while remaining surprisingly constant in its purpose. The icon, no matter the artistic influence, links the viewer directly to the dawn of Christianity when many of the early practitioners were illiterate and relied on visual information to understand the World.

In order to understand the language of the icon the viewer must desire to meet with this reality: to enter into it, the viewer needs to learn to read the icon. The icon must not be regarded as a simple illustration of the Gospels or other theological texts. Visual form and Word are fused together to penetrate an alternate reality.

An iconography is a particular range or system of types of image used by an artist or artists to convey particular meanings. For example in Christian religious painting there is an iconography of images such as the lamb which represents Christ, or the dove which represents the Holy Spirit. In the iconography of classical myth however, the presence of a dove would suggest that any woman also present would be the goddess Aphrodite or Venus, so the meanings of particular images can depend on context.

The production of these small images, painted on wooden panels in an egg-yolk medium, was promoted after the 13th century by a whole series of circumstances. In the first place the practice grew up of hanging at least two rows of icons on the iconostasis (screen bearing icons, separating the sanctuary of many Eastern churches from the nave), considerably increasing the number required; the larger icons in the lower tier represented Christ, or the Virgin and Child, or the patron saint of the church, while on the upper tier were icons of the liturgical festivals, the Deisis or scenes from the lives of saints. A second factor was that in time of disturbance or danger to the Faith - as a result, for example, of the victories of the infidels - one of the ways in which ordinary people could seek reassurance and express their confidence and hope was to have in their homes images of Christ, the Virgin or the various saints to which they could address their prayers more easily and more frequently than in church. Gradually, therefore, each family came to have their own icons, varying inequality and costliness according to their resources. Theses icons now provide his historian with a mass of evidence, enabling him to observe the long continuance of traditional forms.

The icon-painters were not much given to innovation: they sought to reassure the faithful that the image would preserve its efficacy and power, and the best way of achieving this was to maintain the traditional patterns which were familiar to all. As time went on, however, other influences came into play alongside this conservative trend. In Eastern Christendom, where much of the population had fallen under the Turkish yoke while other areas remained independent, there was not the same cohesion aa before 1453, nor the same close links with the capital. In Crete, and later even more strongly in the Ionian Island, which still belonged to Venice, Italian influences were powerfully felt. In Russian and elsewhere artist expressed their religious ideal in forms which were no longer wholly Byzantine.

Iconography (or iconology) is also the academic discipline of the study of images in art and their meanings.

Source: Museum of Russian Icons and www.tate.org/art-terms/iconography

Icons illustrate the links and continuity of Greek art and culture from Late Antiquity, through Byzantium, to the present.

Byzantine Icons

Go to: www.ancient.eu/article/1161/byzantine-icons/

Go to: www.ancient.eu/article/1161/byzantine-icons/

Painting on Wood

14th Century

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

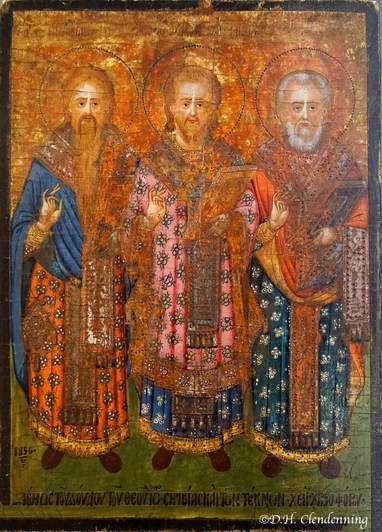

Four Chosen Byzantine Saints

At the top Saint Anthony the Great, George the Great Martyr and in the lower register Peter on the left and Paul on the right. The icon maintains its entirely Byzantine character and material nature, and the idiom that the painter uses bears limited resemblance of the characteristic of the Cretan School.

At the top Saint Anthony the Great, George the Great Martyr and in the lower register Peter on the left and Paul on the right. The icon maintains its entirely Byzantine character and material nature, and the idiom that the painter uses bears limited resemblance of the characteristic of the Cretan School.

|

The Virgin is seated on an Imperial carved wood throne with a wood plinth as support for her feet. Both furnishing are decorated with extensive gilt details, and she sits on a large red silk elongated pillow. The angels are dressed in the attire of attendants in the Imperial palace who carry Imperial authority as well. They are guard and servants at the same time.

The iconography in entirely Byzantine. It is an icon subject matter without the intrusion of later western influences, but also, this iconography transforms into the subject known as "Virgin Mary Queen of Heavens". The small triptych, 6 5/8" x 8 3/4", was made for personal adoration and as an object to be carried on one's body for protection and prayer. |

15th Century

|

The Autonomous Monastic State of the Holy Mountain

A male-only holy retreat, Mount Athos is located on a peninsula in northern Greece that is the spiritual heart of the Eastern Orthodox Church. The monastery holds on to to the traditions of Byzantium when the might of the Byzantine Empire meant Greek culture dominated the eastern Mediterranean. There have been monks on Mount Athos since the sixth century, with monasteries still ruling the Julian calendar, 13 days behind the more common Gregorian calendar. Doing he day the monks work -- gardening, cooking, painting icons -- until is it time for vespers before sunset. |

|

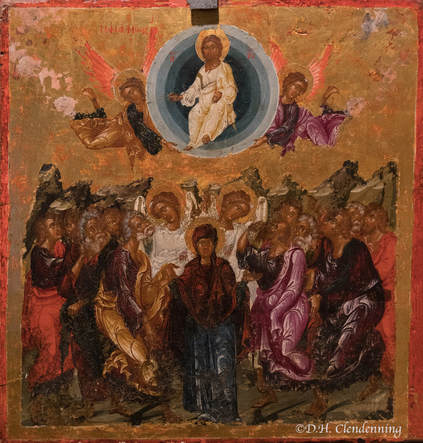

Icons are religious objects that operate quite differently from the western European works. Rather than simply representing spiritual subjects, icons are considered direct portals to the divine. Icons capture the essence of the depicted figure and serve as a direct intercessor for the worshipper. They are instruments for establishing contact with God and remain a critical element of worship in the Orthodox Church.

God resting is a rare subject in both Western and Russian icons, indicating that the owner would have been a priest or a highly educated lay person who used the icon for private devotion. It represents the Old Testament book of Genesis 2:3: "And he blessed the seventh day, and sanctified it: because in it he had rested from all his work which God created and made." |

The Nationalmuseum, Stockholm has an outstanding collection of Russian and some Byzantine icons. Icons are the sacred images of the Orthodox Church. They have their own long-standing visual symbolism which differs radically from that of Western art. Their two-dimensionality, stylization and abstract qualities have provided important sources of inspiration from artist throughout the 20th century up until today.

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

16th Century

17th Century

18th Century

19th Century

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

Iconic Russian Icons

|

Russian Art on its Byzantine roots

Russian icons are typically paintings on wood, often small, though some in churches and monasteries may be much larger. The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity in AD 988. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by Byzantine art, led from the capital in Constantinople. As time passed, the Russians widened the vocabulary of types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere in the Orthodox world. Russian Icons were an important aspect of medieval religious life in eastern Europe. Many of these beautiful sacred "images" are now considered to rank with Europe's great pictorial masterpieces. "Stemming from the ancient Egyptian tomb portraits, it was in Russia, converted to Christianity only at the end of the tenth century, that this art became of paramount importance. Russian painters soon became inspired by icons to produce their finest pictorial works, and to create a school of painting which has rarely been surpassed in depth of religious feeling." Icons, Tamara Talbot Rice, 1959 |

A series of reprographics of Russian icons following traditional stylization

Click on images to enlarge

St. George and the Dragon

The legend of St. George and the Dragon tells of a terrible dragon that demanded human offerings from the town of Selene as its price for not laying waste to the town. The day the King's daughter is to be sacrificed, St. George comes riding by. On condition that the town's heathen inhabitants convert to Christianity, he slays the dragon.

The legend of St. George and the Dragon tells of a terrible dragon that demanded human offerings from the town of Selene as its price for not laying waste to the town. The day the King's daughter is to be sacrificed, St. George comes riding by. On condition that the town's heathen inhabitants convert to Christianity, he slays the dragon.

|

Saint Paraskeva was born in Rome of devout Christian parents in the year 140 A.D. At that time, there were less than fifty thousand Christian in the world.

With her strong faith she persuaded many people to forsake their pagan idols and commit themselves to her faith in Jesus Christ. She continued her missionary endeavours despite being persecuted by the Roman emperors Antonius and Marcus Aurelius. She was finally put to death as a martyr to her faith. In her high hand, she hold a cross, sign of her martyrdom. In her left hand, she holds a scroll inscribed in Old Church Slavonic. In Greek, Paraskeva is the word for Friday. With Friday being the traditional market day, Saint Paraskeva is venerated as Patron of the marketplace and commerce. This panel was most likely a church icon, probably from the local tier of an iconostasis in a rural church. |

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

There is a rich history and elaborate religious symbolism associated with icons. In Russian churches, the nave is typically separated from the sanctuary by an iconostasis, or icon-screen, a wall of icons with double doors in the centre. Icons are considered to be the Gospel in paint, and therefore careful attention is paid to ensure that the Gospel is faithfully and accurately conveyed.

Old Russian icons are often slightly concave due to the natural warpage of the wood - sign of originality. All photos are of original icons from a private Russian Icon Collection in North America.

References

The Pictorial Metaphysics of the Icon: Abstraction vs. Naturalism Reconsidered

Post of 3 in the series:

Part 1. Go to link: orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-pictorial-metaphysics-of-the-icon-abstraction-vs-naturalism-reconsidered/

Part 2. Go to link: orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-pictorial-metaphysics-of-the-icon-part-ii/

Part 3. Go to link: orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-pictorial-metaphysics-of-the-icon-part-iii/

Post of 3 in the series:

Part 1. Go to link: orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-pictorial-metaphysics-of-the-icon-abstraction-vs-naturalism-reconsidered/

Part 2. Go to link: orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-pictorial-metaphysics-of-the-icon-part-ii/

Part 3. Go to link: orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-pictorial-metaphysics-of-the-icon-part-iii/

Iconography

Go to: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iconography

Go to: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iconography