ENCOUNTERING BEAUTY THROUGH THE MATERIAL WORLD

SURFACE TEXTURES - Versatile Materials used for art such as Marble, Stone, Wood, Pigment, Bronze, Glass, Ceramic and Precious Stone.

Architectural Ornamentation & Built Heritage |

Surface Textures |

Sculpture |

Wood |

Painting |

Stone |

Mosaics and Tiles |

Marble |

Stained Glass |

Brick |

Public Sculpture |

Plaster |

Fountains |

Stucco & Aggregates |

Great Houses |

Fabric |

Temples |

Metal |

Villas |

Clay for Terracotta & Tiles |

Cathedrals and Cemeteries |

Glass |

Over 2021, London Masterpiece will offer videos, podcasts, panel discussions on Encountering Beauty through the Material World discussing versatile materials used for art such as Marble, Wood, Pigment, Bronze, Ceramic and Precious Stone.

For a list of upcoming London Masterpiece events,

Go to: email.llanalytics.com/display.php?M=61511407&C=00903436bcc1994cfe0fecc26a790bd6&S=1315339&L=17091&N=19307

Go to: email.llanalytics.com/display.php?M=61511407&C=00903436bcc1994cfe0fecc26a790bd6&S=1315339&L=17091&N=19307

Importantly, the London Masterpiece series will reinforce the work on Architectural Surfaces viewed on this website

Architectural Surfaces

Details for Artists, Architects, Designers, Illustrators Picture Editors and Art Collectors

Clendenning Architectural Surfaces

This site is a inspiring visual resource for architecture, decorative, botanical, and landscape images. Clendenning's library is a major source of architectural surfaces, organized specifically for artists, architects, designers, illustrators, picture editors and art collectors.

This site is a inspiring visual resource for architecture, decorative, botanical, and landscape images. Clendenning's library is a major source of architectural surfaces, organized specifically for artists, architects, designers, illustrators, picture editors and art collectors.

Monumental Art

Clendenning Images of Monumental Art were taken from sites from antiquity through the ages to the present. Monumental art embraces a broad range of works created to harmonize with a specific architectural environment both in theme and in structural and chromatic design. Monumental art includes monuments, architectural ornamentation (sculpture, painting, mosaics and tiles) stained glass, public sculpture, and fountains. and built heritage structures such as great houses, temples, villas, cathedrals and famous cemeteries.

Architectural Designs from Antiquity

In architectural decoration, surface textures were designed in different materials, including wood, stone, marble, brick, plaster, stucco, aggregates, metal, tile, and glass, ready to be used for trompe l’oeil artists, architects and designers.

Clendenning Website

Decorative designs are organized by architectural building elements such as walls, facades, windows, doorways, ceilings, roofs, floors, pavements, columns, and arches.

The Clendenning website has developed a number of theme collections in tiles, stained glass and Russian icons. Under construction are themes in metal and stone decorations.

Photos are numbered and cross-reference in an index theme for easy reference. All images are Copyright by David Clendenning and may not be used commercially with out his express permission.

Clendenning Images of Monumental Art were taken from sites from antiquity through the ages to the present. Monumental art embraces a broad range of works created to harmonize with a specific architectural environment both in theme and in structural and chromatic design. Monumental art includes monuments, architectural ornamentation (sculpture, painting, mosaics and tiles) stained glass, public sculpture, and fountains. and built heritage structures such as great houses, temples, villas, cathedrals and famous cemeteries.

Architectural Designs from Antiquity

In architectural decoration, surface textures were designed in different materials, including wood, stone, marble, brick, plaster, stucco, aggregates, metal, tile, and glass, ready to be used for trompe l’oeil artists, architects and designers.

Clendenning Website

Decorative designs are organized by architectural building elements such as walls, facades, windows, doorways, ceilings, roofs, floors, pavements, columns, and arches.

The Clendenning website has developed a number of theme collections in tiles, stained glass and Russian icons. Under construction are themes in metal and stone decorations.

Photos are numbered and cross-reference in an index theme for easy reference. All images are Copyright by David Clendenning and may not be used commercially with out his express permission.

All images taken in museums (marked by "RN") are not for sale and are for educational purposes only

Decorative Surfaces on Stone

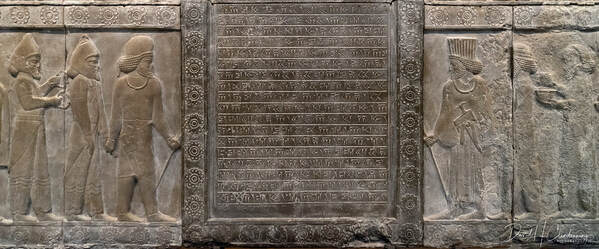

The tradition of decorating royal residences with sculpture began with Ashurnasipal 11 (reigned 883-859 BC) in the North-West Palace at Nimrud. The reliefs from this and later palaces show kings hunting, fighting and engaged in religious ceremonies. Early reliefs are usually inscribed in cuneiform script with records of the exploits of the kings; later, short captions were used. Many preserve traces of paint, of paint, especially on eyes, hair and sandals.

In 612 BC the Assyrian cities were looted and destroyed by invading Babylonians and Medes. The sculptures remained buried in the ruins until the mid-19th century, when many were excavated by British and French archaeologists.

In 612 BC the Assyrian cities were looted and destroyed by invading Babylonians and Medes. The sculptures remained buried in the ruins until the mid-19th century, when many were excavated by British and French archaeologists.

Old Persian cuneiform inscription.

This inscription is written in an ancient script called cuneiform. It records that King Artaxerxes 111 (ruled 359-338) rebuilt the staircase on which this inscription was carved. The staircase was a later alteration to the Palace of Darius.

Nineteenth-century plaster cast taken from sculptures on the Palace of Darius at Persepolis, Iran.

This inscription is written in an ancient script called cuneiform. It records that King Artaxerxes 111 (ruled 359-338) rebuilt the staircase on which this inscription was carved. The staircase was a later alteration to the Palace of Darius.

Nineteenth-century plaster cast taken from sculptures on the Palace of Darius at Persepolis, Iran.

The provinces of Partha and Bactria were in what are now parts of eastern Iran, Afghanistan and central Asia. These men are shown wearing knotted headbands, belted tunics, baggy trousers and hight boots, and carry different sorts of drinking bowls and lead a two-humped (Bactrian) camel (not shown in this panel). Modern cast taken from sculptures on the Apadana at Persepolis, Iran (British Mueusm).

Founders of the Western World - Greece and Rome

Stone carved columns of the Temple of Apollo at Didyma

This panel from a four-sided sarcophagus (coffin) is richly decorated with two theatre masks flanking the head of the Gorgon Medusa, framed by lush formal swags held up by Cupide and winged fingers of victory. The mask and the snaky-haired Gorgon relate to Roman Funerary beliefs: Medusa was thought to ward off even, while make symbolized the cult of Dionysos and its association with passage to the afterlife.

Decorative Surfaces on Marble

Augustus boasted that he found Rome a city of brick and left it of marble.

Imperial Rome

Most of the visible remains of ancient Rome date from the time of the emperors. Images on coins and the impressive ruins of many of Rome's monuments give an idea of their original appearance.

Augustus was the first emperor. He and his supporters remodelled Rome, leaving a lasting legacy. They rebuilt the Roman forum, the religious, political and administrative hear of the city, as well as theatres, temples, baths, basilicas and porticoes. These monuments, built in the extravagant Corinthian style of architecture, pleased the people, beautified the city and glorified the emperor.

Later emperors also left their mark on the city. Claudius rebuilt the Circus Maximus, Nero built his enormous palace the Domus Area (Golden House), Vespasian erected the Colosseum, Trajan constructed an immense Forum and the Basilica Ullpia and Hadrian built the Pantheon, Several emperors including Titus, Caracalla, and Diocletian built lavish public baths.

Most of the visible remains of ancient Rome date from the time of the emperors. Images on coins and the impressive ruins of many of Rome's monuments give an idea of their original appearance.

Augustus was the first emperor. He and his supporters remodelled Rome, leaving a lasting legacy. They rebuilt the Roman forum, the religious, political and administrative hear of the city, as well as theatres, temples, baths, basilicas and porticoes. These monuments, built in the extravagant Corinthian style of architecture, pleased the people, beautified the city and glorified the emperor.

Later emperors also left their mark on the city. Claudius rebuilt the Circus Maximus, Nero built his enormous palace the Domus Area (Golden House), Vespasian erected the Colosseum, Trajan constructed an immense Forum and the Basilica Ullpia and Hadrian built the Pantheon, Several emperors including Titus, Caracalla, and Diocletian built lavish public baths.

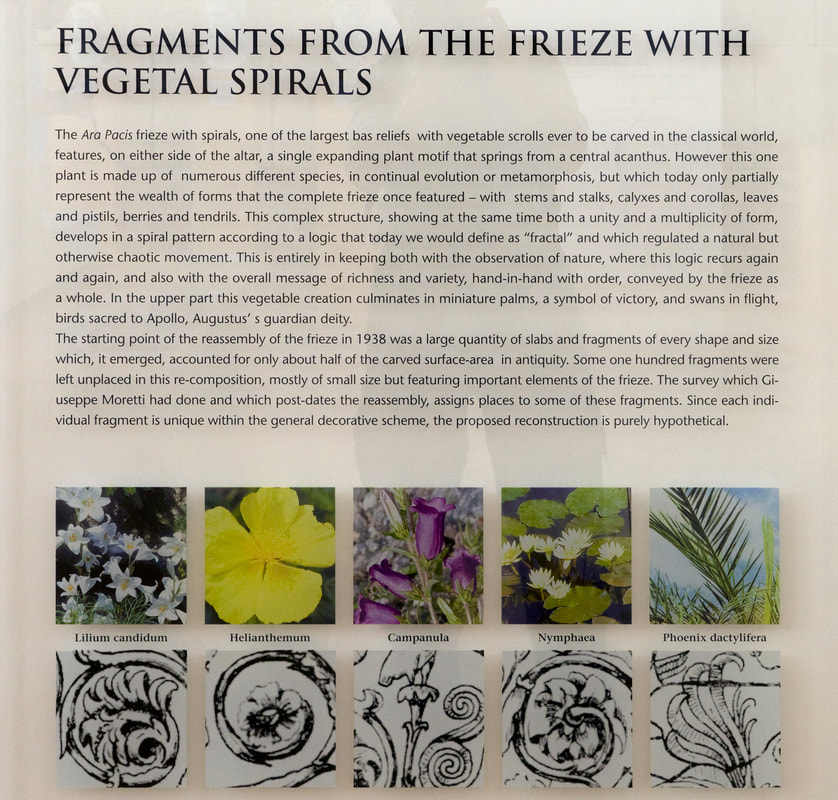

Altar of Augustus Peace in the Campus Martius

Ara Pacis Augustae, Rome. 9 BC. Frieze showing fragments with Vegetal Spirals (lily, rose, bellflower and date plams)

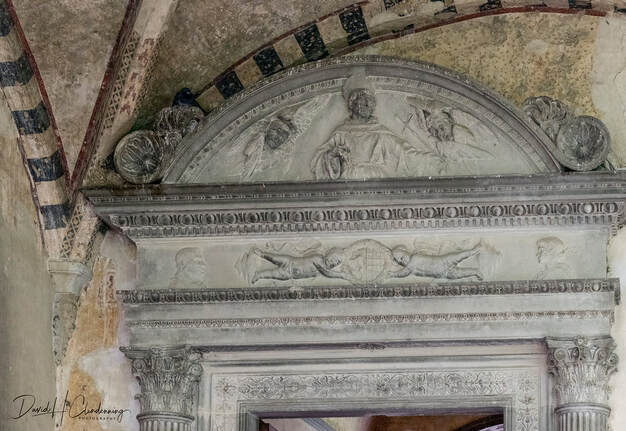

Michelangelo di Ludovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475-1564)

Michelangelo Sacrestia Nuova (New Sacristy) San Lorenzo, Florence - La tomba di Giuliano duca di Nemours, 16th century, Medici chapels.

Decorative Surfaces on Plaster

Architecture in Europe

Architecture in Europe before the eighteenth century was still largely an establishment pursuit. Not that a gifted youth like Palladio or Hawksmoor could not rise by sheer talent, but having risen he would find himself taken into an established circle of other professionals and patrons in whose number would be an influential coterie of wealthy, enthusiastic amateurs.

An architect could even get by without distinctive gifts of draftsmanship, providing the information could be put across by other means. In any event, a Clerk of Works or Master Mason would be at hand to translate outline sketches into finished building. Nor was any deep knowledge of engineering required. Master of the art, like Brunelleschi and Wren, were comparatively rare.

These were, in many ways, happy times for architects, without restrictions from any building codes, planning requirements or the plethora of services now consider3d essential to modern structures. At that time, too, everyday, buildings like smaller houses, farms and shops were put up by builders who relied on architect’s copy books for the finer details and general proportions.

The Industrial Revolution

This was not to last. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, changes were abroad which were to be far reaching. They stirred first in England where colonial prosperity, scientific curiosity and cheap coal and iron combined together to bring about what has come to be called the Industrial Revolution. This was to change the face, not just of England, but ultimately the world.

The invention of the stream engine and development of the locomotive led to an immediate revolution in transport. Coal for furnaces led to improvement in metal manufacture, notably cast iron, which in turn was brought into use for the bridges required for roads and railways. Canal technology flourish. Roads were improved and travel no longer became the prerogative of the rich. The less well-off could move about and did so, deserting a densely populated countryside to look for better wages in the new towns.

With these changes, a new type of designer emerged more of an engineer/builder than architect. They were tough-mined practical men like Thomas Telford (1757-1834), born in Glendinning Scotland, Joseph Paxton (1801-65) and Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-59). Others like Decimus Burton (1800-81), son of a builder, used their practical skills in cast iron to good effect, but, in general, architects sought to conceal the new technology under masonry and stucco, or to disguise it with ornament. The engineers had no such qualms. Brunel’s Clifton suspension bridge and Paxton’s great glass houses (culminating in the Crystal palace) openly celebrated the new material.

An architect could even get by without distinctive gifts of draftsmanship, providing the information could be put across by other means. In any event, a Clerk of Works or Master Mason would be at hand to translate outline sketches into finished building. Nor was any deep knowledge of engineering required. Master of the art, like Brunelleschi and Wren, were comparatively rare.

These were, in many ways, happy times for architects, without restrictions from any building codes, planning requirements or the plethora of services now consider3d essential to modern structures. At that time, too, everyday, buildings like smaller houses, farms and shops were put up by builders who relied on architect’s copy books for the finer details and general proportions.

The Industrial Revolution

This was not to last. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, changes were abroad which were to be far reaching. They stirred first in England where colonial prosperity, scientific curiosity and cheap coal and iron combined together to bring about what has come to be called the Industrial Revolution. This was to change the face, not just of England, but ultimately the world.

The invention of the stream engine and development of the locomotive led to an immediate revolution in transport. Coal for furnaces led to improvement in metal manufacture, notably cast iron, which in turn was brought into use for the bridges required for roads and railways. Canal technology flourish. Roads were improved and travel no longer became the prerogative of the rich. The less well-off could move about and did so, deserting a densely populated countryside to look for better wages in the new towns.

With these changes, a new type of designer emerged more of an engineer/builder than architect. They were tough-mined practical men like Thomas Telford (1757-1834), born in Glendinning Scotland, Joseph Paxton (1801-65) and Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-59). Others like Decimus Burton (1800-81), son of a builder, used their practical skills in cast iron to good effect, but, in general, architects sought to conceal the new technology under masonry and stucco, or to disguise it with ornament. The engineers had no such qualms. Brunel’s Clifton suspension bridge and Paxton’s great glass houses (culminating in the Crystal palace) openly celebrated the new material.

Architecture Detail and Design

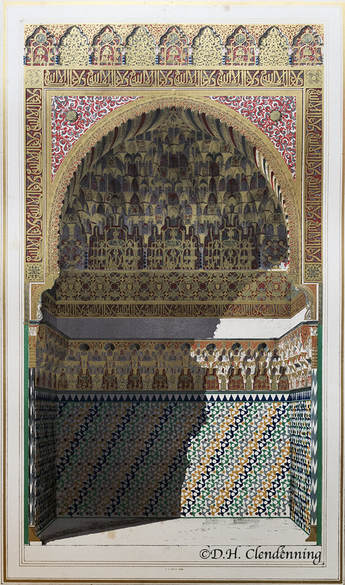

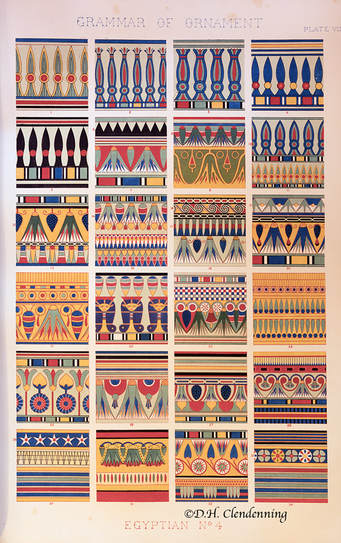

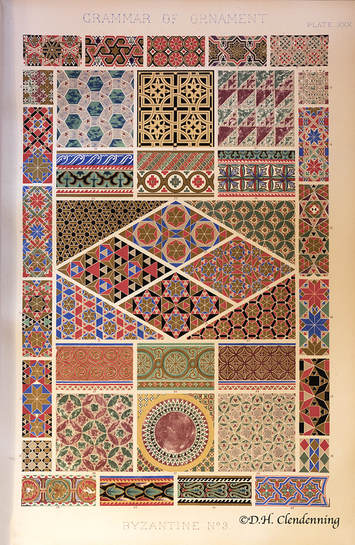

Owen Jones (1809-1874) was one of the most influential design theorists of the 19thcentury and greatly influenced Victorian designs. Jones was passionately interested in historical decoration and ornament from different cultures. His observations on decorative art in “The Grammar of Ornament” were applied to buildings, graphics and products.

He was involved in the decorative aspect of the Crystal Place building of 1851. Exhibitors and visitors to the exhibition were encouraged to apply these designs to their own products. Companies, British and foreign, applied these designs and used them on various surfaces textures (such as iron, marble, wood, paper, textiles, tiles, pottery, etc.) to great effect.

These designs were borrowed from antiquity (Roman, Greek, Persian, Egyptian and Byzantine) and from the Medieval, Renaissance, Elizabethan and Italian styles. Victorian designers were also inspired by Islamic art (Arabian, Turkish, Moroccan). The use of ornament on architecture surfaces embellished the Baroque (1600-1750), Rococo (1720-1780 and Neo-classical (1750-1850) periods.

Owen Jones (1809-1874) was one of the most influential design theorists of the 19thcentury and greatly influenced Victorian designs. Jones was passionately interested in historical decoration and ornament from different cultures. His observations on decorative art in “The Grammar of Ornament” were applied to buildings, graphics and products.

He was involved in the decorative aspect of the Crystal Place building of 1851. Exhibitors and visitors to the exhibition were encouraged to apply these designs to their own products. Companies, British and foreign, applied these designs and used them on various surfaces textures (such as iron, marble, wood, paper, textiles, tiles, pottery, etc.) to great effect.

These designs were borrowed from antiquity (Roman, Greek, Persian, Egyptian and Byzantine) and from the Medieval, Renaissance, Elizabethan and Italian styles. Victorian designers were also inspired by Islamic art (Arabian, Turkish, Moroccan). The use of ornament on architecture surfaces embellished the Baroque (1600-1750), Rococo (1720-1780 and Neo-classical (1750-1850) periods.

Designs from the Past

ANTIQUITY |

EARLY PERIODS |

Egyptian |

Medieval |

Greek |

Elizabethan |

Roman |

Renaissance |

Byzantine |

Italian |

Persian |

Islamic |

Chinese |

Victorian |

Colour Printing

Owen Jones efforts to record and illustrate Islamic art and architecture lead to his first great publication, Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra, 1842-5, at which he worked at perfecting the relatively new process of colour printing, chromolithography.

Owen Jones efforts to record and illustrate Islamic art and architecture lead to his first great publication, Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra, 1842-5, at which he worked at perfecting the relatively new process of colour printing, chromolithography.

Some architects and critics looked on in dismay the threat to the landscape and towns which the new industrialization was bringing in its wake. But the impetus of industry could not be stopped. Its technology spread abroad, finding ready talents to exploit it if France and Italy. It moved to the United States where it took immediate root and provided the foundations for the skyscraper. This was in the future, in the meantime the Classical tradition was slowly waning, and much of the original Renaissance spirit was by now exhausted. Detailing became coarse, infected by the nouveau riche ostentation of the rising middle classes and the fruits of capitalism.

Neo-Classicism

Those who could find no comfort in either an out warn Classicism or in the more robust works of the new engineers, turned back to the past for comfort and inspiration. Renaissance architects had always modified the classical grammar to suit the times.; Palladio, Mansart, Kent and the New England architects bear witness to their success.

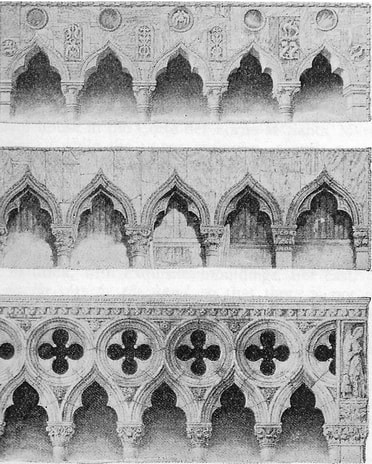

This was not enough from men like A. W. N. Pugin (1812-52) and George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), for whom a total commitment to the past was essential. This movement, the Gothic Revival, was championed in England by the critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) who, during a honeymoon in Italy fell in love with the early buildings of Venice This resulted in The Stones of Venice (1851-53), one of the most influential works of its time both at home and abroad. It changed the face of Britain. The Venetian arches and fruiting capitals of suburban houses stem directly from his book, however much he later deplored the way his careful illustrations had been debased by the speculative builders.

England was by no means alone in returning to the past: the movement was alive in Europe, particularly in Germany and Austria. Classical architecture held its own, popular with the establishment in every country. Queen Victoria, in spite of the new Gothic Houses of Parliament, chose Italianate for her house on the Isle of Wright. There was much popular controversy and what has come to be known as the “Battle of the Styles” raged for most of the nineteenth century. However, a reaction set in against the severities of the revival.

Art and Crafts style

In England, William Morris (1834-96), taking a generally Ruskinian line, liberated design with his workshop-biased approach to a simpler, if still medieval, architecture. To him the Great Exhibition of 1851, had been a tawdry disaster. The new style, “Art and Crafts”, developed eventually into a form of “Art Nouveau”, a new movement which Victor Horta (1861-1949) had initiated in Brussels.

Those who could find no comfort in either an out warn Classicism or in the more robust works of the new engineers, turned back to the past for comfort and inspiration. Renaissance architects had always modified the classical grammar to suit the times.; Palladio, Mansart, Kent and the New England architects bear witness to their success.

This was not enough from men like A. W. N. Pugin (1812-52) and George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), for whom a total commitment to the past was essential. This movement, the Gothic Revival, was championed in England by the critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) who, during a honeymoon in Italy fell in love with the early buildings of Venice This resulted in The Stones of Venice (1851-53), one of the most influential works of its time both at home and abroad. It changed the face of Britain. The Venetian arches and fruiting capitals of suburban houses stem directly from his book, however much he later deplored the way his careful illustrations had been debased by the speculative builders.

England was by no means alone in returning to the past: the movement was alive in Europe, particularly in Germany and Austria. Classical architecture held its own, popular with the establishment in every country. Queen Victoria, in spite of the new Gothic Houses of Parliament, chose Italianate for her house on the Isle of Wright. There was much popular controversy and what has come to be known as the “Battle of the Styles” raged for most of the nineteenth century. However, a reaction set in against the severities of the revival.

Art and Crafts style

In England, William Morris (1834-96), taking a generally Ruskinian line, liberated design with his workshop-biased approach to a simpler, if still medieval, architecture. To him the Great Exhibition of 1851, had been a tawdry disaster. The new style, “Art and Crafts”, developed eventually into a form of “Art Nouveau”, a new movement which Victor Horta (1861-1949) had initiated in Brussels.

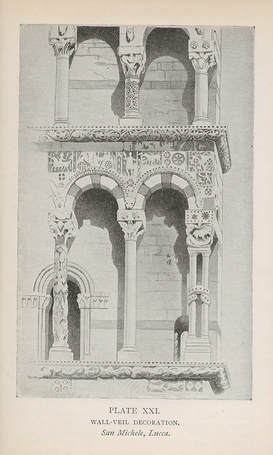

Stone and Marble Lucca Cathedral dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. Begun in 1060.

San Michele in Foro, c. 1080, is a Roman Catholic basilica church in Lucca, Tuscany, built over the ancient Roman forum. Romanesque architecture.

Ruskin's main message of his book was that architecture could exert a moral influence upon society. Medieval buildings, with their ebullient ornaments, allowed individual expression.

Architecture in the USA

All this time the United States was growing in prosperity and intellectual self-confidence. A new and wholly American architecture emerged, notably in the robust mid-West which was free of European ties and the conservatism of New England. From Chicago came the first great commercial building of Louis Sullivan (1856-1924). Frank Lloyd Wright (1869-1959), established his practice in the expanding suburbs of Oak Park, Chicago producing a spectacular collection of houses of exceptional individuality and talent. American architecture became of international importance.

In all the countries of the West, forces were combining to form the “New Architecture” The United States had made its own contributions with the skyscraper, but the hard core of the new architecture was in the hand of Horgta in Belgium, and Otto Wagner (1841-1918) in Austria. In Britain, the turn of the century saw a reaction to the Victorian, only in the earnest vernacular of Charles F. Voysey (1857-1941) and Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944). In Europe, Art Nouveau died almost stillborn. The public had always viewed it with suspicion, associating it with bohemian aestheticism. Its formal licence prevented easy adaptation to standardized building components such as doorways and windows. Ornament for its own sake seemed suddenly less relevant. Alfred Loos (1870-1933) in Austria went further. “Ornament is Crime”, he said, and the foundations of future Modernism and the International Style were laid. The romantic movement generally failed.

All this time the United States was growing in prosperity and intellectual self-confidence. A new and wholly American architecture emerged, notably in the robust mid-West which was free of European ties and the conservatism of New England. From Chicago came the first great commercial building of Louis Sullivan (1856-1924). Frank Lloyd Wright (1869-1959), established his practice in the expanding suburbs of Oak Park, Chicago producing a spectacular collection of houses of exceptional individuality and talent. American architecture became of international importance.

In all the countries of the West, forces were combining to form the “New Architecture” The United States had made its own contributions with the skyscraper, but the hard core of the new architecture was in the hand of Horgta in Belgium, and Otto Wagner (1841-1918) in Austria. In Britain, the turn of the century saw a reaction to the Victorian, only in the earnest vernacular of Charles F. Voysey (1857-1941) and Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944). In Europe, Art Nouveau died almost stillborn. The public had always viewed it with suspicion, associating it with bohemian aestheticism. Its formal licence prevented easy adaptation to standardized building components such as doorways and windows. Ornament for its own sake seemed suddenly less relevant. Alfred Loos (1870-1933) in Austria went further. “Ornament is Crime”, he said, and the foundations of future Modernism and the International Style were laid. The romantic movement generally failed.

Decorative Surfaces on Cast-Iron

Interior of University Musuem of Natural History, B. Woodward, (1855-60), Oxford .

In the 'Veronese' Gothic style

From the mid-century iron became increasingly used in conjunction with masonry.

The glass and iron roof supported by cast iron pillars/columns resembling branches of trees, including Sycamore, walnut and palm. The capitals were superbly decoratived with naturalistic flower, leaf and fruit designs. The architects, Den & Woodward, were personally encouraged by John Ruskin (1819-1900). Inside is all light and lacy - Neo-Gothic translated into industrial cast-iron tracery, a perfect fusion of historicism and contemporary funtionalism. Comparisons could be made between the skeleton construction of the Gothic cathedrals and those possible with the use of iron.

In the 'Veronese' Gothic style

From the mid-century iron became increasingly used in conjunction with masonry.

The glass and iron roof supported by cast iron pillars/columns resembling branches of trees, including Sycamore, walnut and palm. The capitals were superbly decoratived with naturalistic flower, leaf and fruit designs. The architects, Den & Woodward, were personally encouraged by John Ruskin (1819-1900). Inside is all light and lacy - Neo-Gothic translated into industrial cast-iron tracery, a perfect fusion of historicism and contemporary funtionalism. Comparisons could be made between the skeleton construction of the Gothic cathedrals and those possible with the use of iron.

Parliamentary Library, Ottawa; Thomas Fuller and C. Jones, 1859-67

Gothic Revival buildings were to be found throughout the Victorian Empire. The Ottawa library is a beautifully proportioned building, modelled closely on a medieval chapter house, on a much enlarged scale.

Gothic Revival buildings were to be found throughout the Victorian Empire. The Ottawa library is a beautifully proportioned building, modelled closely on a medieval chapter house, on a much enlarged scale.

|

Louis Comfort Tiffany - Impressions on Film, Canvass and Paper

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1818-1933) established his reputation creating beautiful objects. His glass objects made his a beloved American artist. Tiffany is less well known for two-dimensional works. Tiffany, who traveled broadly, was increasingly engaged with his visual environment, recording his impressions with camera, brush, and pen. Tiffany captured this impression of the Library of the Canadian Parliament in 1919 after the terrible fire of 1916 which destroyed the main building. The library was untouched by the fire and the main building was completely re-built. |

Decorative Surfaces on Metal, Steel & Aluminum

The development of the use of iron, especially the iron girder, had suddenly appeared for use by Western architects and finally broke the inherited Hellenizing architectural custom and tradition. As the Hellenic Renaissance shifted slowly to “a Gothic Revival” style, the use of iron was adapted and could be seen, for example, in the cast-iron roof interior of the Museum of Natural History at Oxford (1855-61) and the Woolworth Building in New York (1910-13).

Hamlin Hall, Robert College, Constantinople: The First Non-Gothic Architecture Structure of Stone and Iron

The first Westerner to think of turning the iron girder to use as a building material without drawing a “Gothic” veil over his building was not a professional architect but an imaginative amateur, the American missionary Cyrus Hamlin. The site on which he erected his historic structure overlooked the shores of the Bosphorus, not the banks of the Hudson. The nucleus of Robert College, Hamlin Hall, dominating Mehmed the Conqueror’s Castle of Europe was built by Dr. Cyrus Hamlin in 1869-71.

In Hamlin Cyrus’s book, “Among the Turks (London 1878, Sampson Low), p. 297, he referred to “the building as 113 feet by 103. …The stone is the same as that of the fortress built in A. D. 1452-3.… It is fire-proof, the floors being of iron beams with brick arches”. The seed sown by Hamlin in Constantinople bore fruit in a Western World that was Brunel’s (British engineer, 1806-1859) as well as Hamlin’s homeland. Hamlin’s building was the first non-Gothic architecture structure of stone and iron. Iron has been married to glass in the revolutionary Crystal Palace and had been used in bridges earlier still, the first being The Ironbridge ( a 100-foot cast iron bridge that open in 1781). From this period on iron became increasingly used in conjunction with masonry. By about 1890, steel frames would enable skyscrapers. The steel-framed Woodworth Building, and much of early twentieth-century New York, was a halfway house. But while it was going up, so were the earliest examples of modernism in the U.S.

Decorative Surfaces on Wood

Decorative Surfaces on Stucco - Panel Painting

Title: Wall Painting of Columbus Landing,

Order No.: A1-4151.

Location: La Gormera, Canary Islands

Title: Wall Painting of Columbus Landing,

Order No.: A1-4151.

Location: La Gormera, Canary Islands

La Iglesia de la Asuncion de San Sebastian de La Gomera, c. 1450. Canary Islands

The last church where Columbus prayed before discovering America, 1492. He stopped here later during his further expeditions in 1493 and 1498. The original church was destroyed by a fire. The 18th-century church today is constructed in the form of a Latin cross and has three naves and mixes Mudejar (Islamic-style architecture), Gothic and baroque architecture styles.

The last church where Columbus prayed before discovering America, 1492. He stopped here later during his further expeditions in 1493 and 1498. The original church was destroyed by a fire. The 18th-century church today is constructed in the form of a Latin cross and has three naves and mixes Mudejar (Islamic-style architecture), Gothic and baroque architecture styles.

Decorative Surfaces on Canvas - Frescoes

Piero Della Francesca (1416-1492) - Early Renaissance

The paintings of Piero della Francesca are dispersed throughout Tuscany, Umbria and the Marches, still largely in the locations for which they were painted. Piero's artistic beginning started in Sansepolcro. This mediaeval town hosts the fresco, Resurrection of Christ, "the best painting in the World", according to Aldous Huxley.

The paintings of Piero della Francesca are dispersed throughout Tuscany, Umbria and the Marches, still largely in the locations for which they were painted. Piero's artistic beginning started in Sansepolcro. This mediaeval town hosts the fresco, Resurrection of Christ, "the best painting in the World", according to Aldous Huxley.

Early Indigenous Travellers in Canada

Decorative Surfaces on Paper

Title: Carpets from Turkey, No. 13, Chromolithograph, published by Day & Sons, London.

Order No.: A1-1500

Location: Private collection, Ottawa.

Title: Carpets from Turkey, No. 13, Chromolithograph, published by Day & Sons, London.

Order No.: A1-1500

Location: Private collection, Ottawa.

Day & Son (1823-1867) was a major British lithographic firm of the second third of the nineteenth century. The firm was granted the status of 'Lithographer to Queen Victoria' in 1837. In 1851, The firm produced the book The industrial Arts of the Nineteenth Century. The firm was taken over by Vincent Brooks in 1867.

Decorative Surfaces on Textiles (cotton, wool, linen, hemp)

Cuba - A study in contradictions, pastels and primary colors, rich and poor, the past and the future.

Decorative Surfaces on Terracotta & Tiles

Damascus Tiles

Decorative Surfaces on Stucco work and Plaster

Click on photo to enlarge